Andrew Oh-Willeke points us to this, on the job market for lawyers:

Slightly more than half of the class of 2011 — 55 percent — found full-time, long-term jobs that require bar passage nine months after they graduated, according to employment figures released on June 18 by the American Bar Association.

I couldn’t find a comparable figure for medical graduates on a quick search, but I’m guessing the number’s in the low single digits.

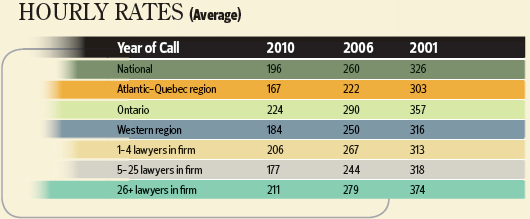

The lawyer glut has been going on for a while, and at least in Canada (the only place I’ve found data) it’s been having predictable effects on legal fees — down 40% in nine years ’01–’10:

I doubt that doctors’ fees are the prime driver behind our crisis of rising health-care costs (what providers charge). But at least one analysis says it’s an important part (Todd Hixon, Forbes):

U.S. spending annual on physicians per capita is about five times higher than peer countries: $1,600 versus $310 in a sample of peer countries, a difference of $1,290 per capita or $390 billion nationally, 37% of the health care spending gap. These conclusions come from an analysis co-authored by Miriam Laugesen of the Columbia University School of Public Health and Sherry Gleid, an Assistant Secretary in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (source)**.

This suggests that relieving the supply shortage — especially for primary care doctors — could have a big impact. Not a new insight, but I thought this data point would be of interest.

Update: In response to WH10’s good comments, perhaps some better thinking:

Maybe the answer’s to relieve the shortage of specialists, driving down their compensation and making primary care (relatively) a more attractive career option.

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

6 responses to “What if the Doctor Market Was Like the Lawyer Market?”

The problem is that we have a supply shortage of primary care physicians in part because compensation is so poor for them. Many propose raising payments to primary care physicians to attract more of them. That would seem to increase costs (higher salaries + more physicians), at least in the short-run. However, perhaps you also get some savings if the greater availability of PC docs drives people to them instead of specialists. In the long run, you might also get some savings if the greater supply of PC docs enables more preventative care and/or cures illnesses before they get more serious. However, I ran across this article the other day, which claims that preventative care doesn’t drive down healthcare costs http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/28/1/42.abstract. I haven’t read it yet though, and it doesn’t look like it includes indirect societal economic benefits (such as gains in economic productivity).

https://www.aamc.org/download/150584/data/physician_shortages_factsheet.pdf

Looks like non-PC docs will still be in shortage, so you could get some savings there.

Maybe the answer’s to relieve the shortage of specialists, driving down their compensation and making primary care (relatively) a more attractive career option.

@Asymptosis

That’s interesting. One also wonders if lower compensation, will make it hard to recruit more physicians, or at least quality ones. Seems that might not be so much of an issue abroad, though.

Isn’t that sort of asking, “if a supply increase results in lower prices, won’t that result in a supply decrease”? I have no doubt you could see those kinds of swings, since there’s no more (any more than a very large, general) equilibrium in economies than there is in weather systems. (Is a sunny day “in equilibrium”? A rainy day?)

Right. I guess I was more thinking along the lines of compensation being driven top-down by the Govt via Medicare/Medicare or a future single payer system.