An old friend dropped by recently and we had a few beers on the back deck. He runs his family’s commercial real-estate business; they own and operate half a dozen or so pretty large properties (and just bought another) — a mall, office buildings, mixed use.

I was really curious to talk to him about why commercial property owners don’t invest more in energy efficiency. By all accounts there’s great ROI in doing so — serious low-hanging fruit.

Why do commercial property owners leave five-dollar bills lying on the sidewalk?*

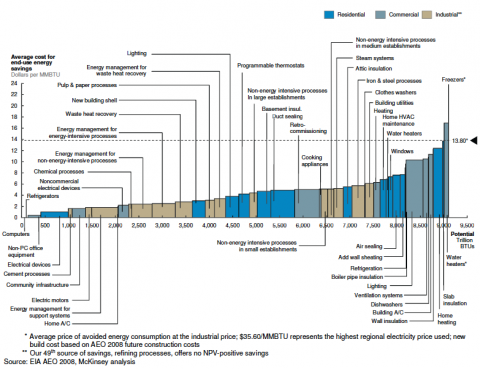

At least, it sure looks like there are five-dollar bills lying around. Here from a McKinsey report (PDF; see page 15) showing how much it costs to save (not buy/pay for) a million BTUs of energy, by instead investing in energy efficiency:

Sorry, it’s hard to see without going to the PDF. But short story: there are quadrillions of BTUs in efficiency savings available for less than $2 per million BTUs.

Now look at the cost of buying a million BTUs instead, to heat your building or power your plant (2011 figures, Energy Information Administration):

Coal: $2.39/MMBTU

Petroleum: $12.48

Natural Gas: $4.72

This is the cost to a utility company buying these fuels. The meter cost of the electricity produced (after line losses, administration, profits, etc.) — the cost for building owners — will of course be somewhat higher.

So it sure seems like there’s money to be picked up. Why don’t building owners do it? The short answer my friend and I came to? Triple-net leases — the ubiquitous standard in the commercial real-estate industry.

In these leases tenants pay per-square-foot rent, plus their pro-rata share (by square feet) of the building’s 1) taxes, 2) insurance, and 3) repairs, maintenance, and energy expenses. (Many NNN leases don’t include pro-rata energy costs, but tenants are separately metered and either pay directly or through the landlord. There are lots of variations, but landlords rarely pay all energy costs.)

Notice what is not included: the cost of improvements — for instance improvements to increase energy efficiency. So the owner gets all the costs, right up front. And the benefits go mostly or completely to the tenants, in the form of lower energy bills.

“But hey,” I asked my friend, “don’t lower energy costs for tenants mean you can charge more rent? Doesn’t it all come out in the wash?”

“Welllllhh,” he said… Most tenants are on long leases. “We just signed a ten-year lease with the anchor tenant for our mall.” My friend won’t see any dollar benefit from those energy savings for a long time, as leases turn over and are renegotiated. And it’s not at all clear how much benefit he’ll get, because tenants tend to fixate on the square-footage rental rate, which would go up.

Imagine you’re a leasing agent for the building, trying to rent some space. You’re competing with other buildings that haven’t done the energy upgrade, so their rent/square foot is lower. You’re stuck saying “yeah yeah yeah yeah but you’ll spend less on energy!” This, if you even get the chance: Prospective tentants scanning the listings might never even call you because your rent is so high.

A building owner considering a big spend for energy efficiency really has to think thrice: would I rather have a million dollars, cash in hand, or the likely but uncertain prospect of higher profits somewhere (perhaps way) down the road? It’s easy to understand why they make the choices they do.

And all of this is true even though there’s money lying on the ground waiting to be picked up.

It’s a classic coordination problem — people acting in their own best-guess best interests, with ridiculously inefficient results — that is caused or at least greatly exacerbated by the institutional convention of triple-net leases. (The reasons the convention arose are yet another subject, about passing off risk and retaining returns.)

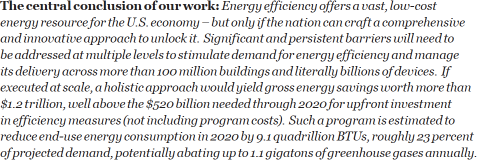

Obviously triple-net is not the sole villain in this very big picture. From the McKinsey report:

Got central planning?

* For those who don’t know the old joke: Two economists walking along, they see a five-dollar bill lying on the sidewalk. One of them gestures for the other to pick it up. “I’m not picking that up,” says the other. “If it were there somebody would have picked it up already!”

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

4 responses to “The Villain of Building Energy Efficiency: Triple-Net Leases. Not Picking the Low-Hanging Fruit”

[…] Cross-posted at Asymptosis. […]

Thank you for this nice article. I’ve been looking for this kind of topic all over the web and found this one interesting.

Feel free to visit my building inspections melbourne site and learn more info.

Thanks for the article. Energy savings and triple net leases have been on my radar for more than 40 years. The problem is well known as stated…”why would a building owner foot the cap ex for energy savings when the benefits go to the tenants”?

The solution has GOT to provide the building owner with a demonstrable financial benefit. Namely, a part of the energy savings must go the the owner’s bottom-line which increases property and loan values. We are working on several multifamily projects that embrace this path and feel it represents an enormous market with equally enormous financial and environmental benefits for all stakeholder.

@Barry Ruby

Very interesting, and pleased to hear it makes sense to another person who’s in the thick of it.

FWIW, I took a small position in Solar City recently, largely because of their financing business model (and the plummeting cost of solar cells).

Very curious: people say that solar is still more expensive than coal plants, but the numbers that Solar City delivers to homeowners suggest that’s not true? Does the model only work because of the buy/sell prices to/from the grid? Given the (somewhat justifiable) complaints we’re hearing from utilities on that front re: the cost of the grid, are those buy/sell differentials sustainable?