JKH likes this line in Keen’s response to Krugman:

The endogenous increase in the stock of money caused by the banking sector creating new money is a far larger determinant of changes in aggregate demand than changes in the velocity of an unchanging stock of money.”

It struck me as an empirical question: how do those changes compare in magnitude? I didn’t know offhand.

Let’s start with MZM (money of zero maturity, the broadest definition of money), and GDP:

There’s about $10 trillion in MZM right now, and GDP (annual spending) is at about $14 trillion.* The money stock turns over about 1.4 times per year.

If money supply was unchanged — no new net lending/borrowing — but the musical chairs/logrolling game sped up so money turnover increased by 5%, because people were more optimistic — ready to take chances, consume now while worrying less about later, invest in new housing and productive capacity, etc. (“animal spirits”) — that would add $.7 trillion to aggregate demand. (5% is quite a GDP jump given no new net lending…)

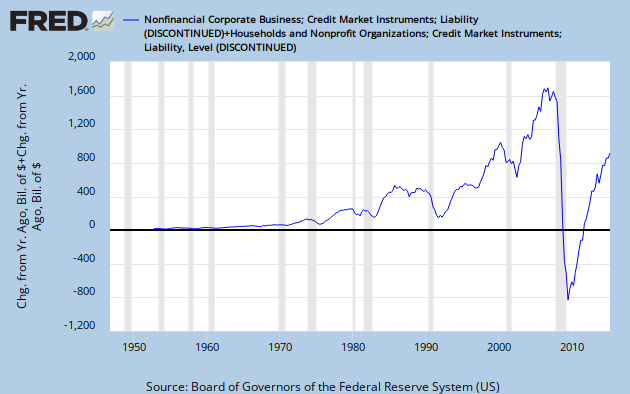

Now lets look at annual net borrowing/lending — annual change in debt owed by households and nonfinancial firms:

Plus $1.6 trillion, to minus $.4 trillion. We’re looking at magnitudes far beyond what we could reasonably expect from pure animal-spirit-driven velocity changes.

Now it’s true that much of that lending/retiring might not translate directly into purchases/production/consumption of real goods. Much of it might (does) leak into changes in financial asset prices. (Keen is keenly aware of this. It’s pure Fisher/Minsky.) Yes, that portion could affect real-good transaction volumes via a second-order wealth effect, but the magnitude of that effect is unclear.

But it seems from the magnitudes that Keen’s statement is probably correct: changes in borrowing and de-borrowing have a lot more potential effect on aggregate demand, at least, than changes in velocity.

* Note that this does not include spending on intermediate goods — those that are turned into final goods within the accounting period — or used stuff. Adding these into total spending when calculating velocity might yield interesting insights. See Nick Rowe, Macroeconomics and the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge.

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

74 responses to “Lending, Velocity, and Aggregate Demand”

There’s a post here on Steve Keen’s usage of aggregate demand and adding change in debt to it:

http://fictionalbarking.blogspot.in/2012/03/steve-keen-terminology-and-walras.html

Here’s a comment from Marc Lavoie who says the same thing as Krugman but in a correct causal way 🙂

http://www.progressive-economics.ca/2011/08/23/recession-ahead/

Comment from Marc Lavoie

Time: August 23, 2011, 1:13 pm

Andrew:

I agree with you that the likelihood of a second recession, even in Canada, is high.

I also agree that a slowdown in credit growth is likely to have a negative effect on aggregate demand and hence on economic activity.

I am rather less enthusiastic than you are about Steve Keen’s accounting, endorsed by Jim Stanford. They are claiming that total aggregate demand, whatever that is, is equal to GDP plus the change in credit. This does not make much sense to me.

There is also a certain amount of double-counting since investment is often financed by credit.

Furthermore, if I get one million dollars in loans to purchase a house, credit goes up by one million; and if the seller of the house puts the proceeds in a bank account, this will have no effect whatsoever on GDP or economic activity. It may only have an impact on the price of houses.

@Ramanan

I think these support my views expressed here. I am also uncomfortable with the GDP+DebtChange=AD construction. Because of the leakage (and yes potential double counting). But it still makes sense to me that as a factual, empirical matter, changes in debt are generally a (much?) more powerful lever on AD than changes in velocity.

@Asymptosis

After reading Marc Lavoie’s point, Krugman’s point seems okay to me.

Steve, while it’s true that the growth in the United States has been credit-driven but one has to describe it in a nice way instead of just adding “change in debt” to GDP and double counting.

What Steve Keen says is nothing new to Post Keynesians at least – that credit creates demand and growth etc. Loan creation leads to expenditure because it creates a cycle of circular flow or income and expenditure.

A model or a definition should make sense in simple cases – which it doesn’t work in the case of Keen’s models.

And Krugman caught him precisely there.

It all makes more sense to me now.

Krugman is smart and much smarter than all mainstream guys. But he is so trained to talk like that it takes time to understand what he says.

Spending that involves a labor component has the greatest effect on aggregate demand.

Spending that simply changes ownership of a good doesn’t seem too important in terms of increasing demand unless the seller turns around and spends on new goods rather than save.

I suspect most of GDP is of the second type.

I think its the mechanically additive definition of aggregate demand that I find troublesome.

Something like mixing an accounting identity with a derivative of one side of that identity, or something.

Its a weird formula with some underlying truth, including a scattering of relevant partial derivatives.

I think one reason why banking is important is so you can understand the operation of central banking in the context of banking. And from there, interest rates. And from there, the relationship of modern monetary operations to ISLM, etc. You have to work hard to adapt ISLM to modern monetary operations, and/or vice versa, but Krugman does it somehow.

@Ramanan

Ramanan, which Krugman point are you referring to? He makes several statements about debt and lending in his article on Keen. Is his article flawless in your opinion?

@Ramanan “A model or a definition should make sense in simple cases – which it doesn’t work in the case of Keen’s models.”

I don’t know that that’s true. The “thought experiment” approach to economics that’s so prevalent leaves me rather cold and unconvinced. In their kind of words: It’s very often partial-equilibrium-y, trying to explain some imagined subsystem, but just plain false when you try to understand the general equilibrium.

Krugman’s simple-case understanding seems to fit that description. “Assume for simplicity that all lending is done by savers.”

@wh10

Keen then goes on to assert that lending is, by definition (at least as I understand it), an addition to aggregate demand. I guess I don’t get that at all. If I decide to cut back on my spending and stash the funds in a bank, which lends them out to someone else, this doesn’t have to represent a net increase in demand. Yes, in some (many) cases lending is associated with higher demand, because resources are being transferred to people with a higher propensity to spend; but Keen seems to be saying something else, and I’m not sure what. I think it has something to do with the notion that creating money = creating demand, but again that isn’t right in any model I understand.”

wh10,

This one.

Initially I found it hard to see what Krugman was trying to say.

If you read this point of Krugman and then read Lavoie from #2, then Krugman makes more sense.

That is Krugman is saying similar things but in a very roundabout way and his point is essentially the same – increase in loans do not have to lead to increase in demand as the person selling the house may not do anything with it.

While it is true that the person in reality will spend some of it, Keen’s model somehow assumes that he will spend everything etc (because he adds change in debt to aggregate demand).

There are two things and this is why I like national accounts.

National accountants have defined everything so that all definitions are in one sense independent of behaviour, change in behaviour of agents. (At least the construction is such to keep it minimal as much as possible).

You can then take them and make a behavioural model but if you start changing definitions at the origin itself then there is an issue.

Keen’s definition is finally double-counting which I think JKH pointed out as soon as Keen came out with his definition a couple of years ago.

I am not saying Krugman’s analysis is flawless but I think he smartly caught Keen!

@Ramanan

Sorry the lines between @wh10 and wh10 is Krugman’s quote

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/27/minksy-and-methodology-wonkish/

Dear Steve:

I’ve finally come to understand why I’ve been so uncomfortable with your notion that GDP+debt-issuance/retirement = Aggregate Demand.

It’s because of something that you understand better than most: much (varying amounts) of new debt issuance doesn’t go into purchase of real goods. It leaks into financial asset prices.

Many like me intuit this, and others understand it explicitly. So they look at that AD construction and say, “that doesn’t make sense.”

And it really doesn’t, given the financial-asset-price dynamic that you understand so well.

Yes: debt issuance and retirement have a huge impact on AD. Based on the magnitude, I’d guess that those annual changes quite overwhelm animal-spirits-driven changes in velocity. But I don’t think you’re serving your own thinking or economics well by sticking to the rather rigid and simplistic construction of AD.

@Ramanan

But you don’t find a problem with the way he is depicting lending, in the sense of the bank needing someone else’s deposits to lend?

@Ramanan

Damn my usage of “you”. I should stop using you. “You” as in a general person, not you specifically 🙂

@Asymptosis

Is that all of your own communication to Keen or the second part a reply?

@wh10 And he then goes on to imply that those savings needed to be transferred, through the act of the loan, to someone else with a higher propensity to spend… This seems to be the opposite of the Post-Keynesian loans –> deposits idea of banking.

@wh10

Yes of course wh10 – I guess that’s why I was put off initially by Krugman’s post!

@Ramanan “increase in loans do not have to lead to increase in demand as the person selling the house may not do anything with it”

Absolutely right. But more borrowing *does* result in more spending, dontcha think? Just not 1:1.

@Ramanan

Ok- I just wanted to make sure, for my own understanding. Thanks!

@Asymptosis

Yes more borrowing can lead to more spending and this spending creates more spending, demand and more borrowing etc etc etc. But one can and should describe it with the usual definitions rather than adding something to GDP.

IMO, Keen seems to know this intuitively but he does so by changing definitions.

There’s no reason to do so. One can still use the standard definitions and make a model which leads to a rapid increase in demand.

“…But one can and should describe it with the usual definitions rather than adding something to GDP…”

For example?

Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh sooooooooo frustratttingggggggggggggggg

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/30/banking-mysticism-continued/

@wh10

🙂

Had to happen. This he did when he criticized the MMTers with the example of the French Franc.

@wh10

There’s such a lack of understanding and lack of coherence here. It’s unbelievable. Krugman is absolutely cornered. All Post-Keynesians and mainstream monetary economists in agreement should come out of the woodwork and absolutely firebomb him on this. If this happened, it would be a historic moment potentially bringing a a paradigm shift to the mainstream.

@Ramanan

Ramanan, yes true! And he got corrected for that and realized his mistake. Hopefully that happens here. After all, this isn’t even “MMT” per se but should be a more widely accepted understanding. Do you think that if he does accept his mistakes here, it would lead to a big shift in his thinking, or no?

@wh10

I can imagine the situation in the conference which Krugman said Keen is attending … and Keen coming up with … I donno … surely will be worth watching.

@wh10

And I really hope vimothy is watching because he gave me (and Ramanan, indirectly) a ton of crap about this the other day 🙂

@Paul

Oh lots of them. These are generally called income-expenditure models but not restricted to them.

The idea is you have C_t, I_t, G_t, T_t, Y_t and so on and you make models with these things at (t+1) dependent on the configuration at t.

@wh10

Yeah!

Krugman says alternative universe etc … forgets that it is tightly connected to the Keynesian principle of effective demand.

R,

My God.

K really doesn’t understand banking operations, does he?

He’s really exposed himself here.

Big disappointment. I never expected anything like that.

I may have to reconsider my opinion of him as an economist.

@JKH

But he is still smart – he has the ability to say come back and impress.

But he has really exposed himself as you say.

Imagine how restless Steve Keen will be to talk in the conference in Berlin mentioned in his post!

Guys, this could be the moment though for PK to start thinking more PK. It’s the sort of exposing that I think could really lead to some productive conversation and actual change in belief sets. Because it’s starting small with one specific issue that is very operational in nature, rather than starting with a theory with tons of baggage.

@Ramanan

@wh10

I’ve always been VERY impressed by him.

But he’s never gone out on an operational limb like this before. And its not the way to describe how the system works.

MMT in particular will be carpet bombing that post.

You guys have a better handle on Keen’s accounting issues, I just haven’t dug into it enough, but if Keen really is doing it wrong and it is leading to some embarrassing conclusions (which may be the case with this AD formula?), I hope it doesn’t discredit the idea of endogenous money loans–>deposits within the mainstream, because Keen could be carrying the torch on this one. @JKH

@wh10

I keep saying I haven’t spent enough time looking at Keen lately. His lectures and videos are wonderful in their own way – probably better than his writing.

As far as the accounting is concerned, he’s forging his own way because he admits to not being up to speed on standard accounting.

Endogenous money is just a fact. That’s whats so shocking about the Krugman post. Hard to believe he doesn’t know how a bank processes a loan out of the gate. I’m really taken aback by that post.

@JKH

Did you really think he believed otherwise, based on all his blogs and papers? And all his colleagues? And most mainstreamers that don’t focus in monetary / banking operations? Am I too cynical?

@wh10

I thought he was an exception. He’s smart enough to fit ISLM to how the real world works – that’s doable simply by fiddling with LM enough. But what isn’t doable is to represent actual banking operations the way he did. That’s a first for him, that I can recall.

@Ramanan “Is that all of your own communication to Keen or the second part a reply?”

A bit of each.

“Plus $1.6 trillion, to minus $.4 trillion. We’re looking at magnitudes far beyond what we could reasonably expect from pure animal-spirit-driven velocity changes.”

Funny. I would say that’s exactly what to expect from animal spirits…

Once again I will say something that goes opposite to what everybody else says. But I think the use of credit — the creation of “endogenous money” I guess — IS THE METHOD BY WHICH WE INCREASE VELOCITY. Otherwise, there are limits to velocity. You cannot spend money faster than you receive income, except by the use of credit.

(So what if this requires a few definitions to be corrected.)

Good footnote, by the way, in your post. Also doesn’t include much of what happens on Wall Street.

“…the creation of “endogenous money†I guess — IS THE METHOD BY WHICH WE INCREASE VELOCITY…”

This is absolutely true and uncontroversial. The problem is it can be and is a dangerous way to increase velocity if not managed properly.

For business and investment it is an absolute necessity.

For consumers and consumption it requires great self-control to not over-leverage and we see how that has worked out.

At the end of the day for any nominal gains to be realized on balance sheets in the aggregate the government must net spend at least in the amount of the gains.

@wh10

Paul Krugman is a Verticalist!

Not surprising – had he realized this, he would have pointed it out but has never. So shouldn’t be too surprising.

A lot of people argue that money is endogenous in NKE – but they continue making the same mistakes.

I think there’s a book by John Taylor of the Taylor rule where he mentions money is endogenous or something of the sort and few pages later talks of the money multiplier!

Yeah, vimothy was saying this, and he describes himself as more of a mainstreamer. I’m not sure what ‘endogenous’ means to him.@Ramanan

Just so it’s clear for those of us not so familiar with bank operations – is the central point people are disagreeing with here Krugman’s statement:

“Bank loan officers can’t just issue checks out of thin air; like employees of any financial intermediary, they must buy assets with funds they have on hand.”

?

@The Arthurian “the creation of “endogenous money†I guess — IS THE METHOD BY WHICH WE INCREASE VELOCITY”

Right, I totally get that borrowing/lending is also driven by animal spirits. Most borrowing is driven by optimism, the desire/willingness to spend on investment and consumption. And lending is driven by confidence in borrowers’ ability to repay in the future.

(Though borrowing can also be driven by the desire of private equity funds and their ilk to squid-suck long-term value out of the businesses they own, ripping off the businesses’ creditors and shareholders in the firms’ inevitable bankruptcies. See here: http://www.asymptosis.com/?p=4212)

I’m actually making that point here, while trying to distinguish between the intertwined effects: that optimism-driven lending/borrowing (and retirement) has a far larger impact on AD than optimism-driven spending increases would absent new net lending/retirement. One of our typical counterfactual arguments.

@Paul “At the end of the day for any nominal gains to be realized on balance sheets in the aggregate the government must net spend at least in the amount of the gains.”

This is true if you look at the economy through the lens of a three-sector model — private, government, external.

But if you de-consolidate private into firms and households, you get a different picture. Through production and the realization of its monetary value through surplus from trade (along with the issuance and market-value increases of household equity claims on firms), you can see wealth increasing — certainly in “real” terms (we have more real stuff per person), and also in financial terms — households’ equity and credit claims against firms. *Gross* financial assets increase, and households’ net financial assets increase, counterbalanced by firms’ right-hand-side “shareholders’ equity.”

That perfectly balanced offset — equity claims vs shareholders equity explains why, arithmetically at least, the private sector can grow in gross terms with no change in net financial assets of the private sector.

This is not to say that extra, “free-floating” money issued by government (embodied, quantified in the accounting construct NFAs) is not necessary for that whole process to happen. A sufficient quantity is by all appearances necessary. (Imagine if government debt/cumulative to-date money issuance was at the same level now as it was in 1900.)

I’ve suggested in the past that government is forced to deficit spend over the long term, to provide those buffer assets for monetization of real gains from production, by the political system. If they don’t do it, recession/depression ensues, and they get voted out of office. This is a very long-term process (and its greatly complicated by Fed actions), but over time, the pressure is inexorable. (See “1900,” above.)

Hey all:

I’m going to hijack this thread slightly, hoping to understand something I haven’t been able to grasp. Hiding my ignorance down here among friends…

I’ve read all the numbingly repetitive and identical explanations of capital-constrained bank lending, how deposits aren’t, can’t be, lent out. But I’m still confused.

If I write a million-dollar check on my account in Bank A and deposit it in Bank B (or roll a wheelbarrow of cash across the street…), what does Bank B do with that million dollars?

A million dollars has passed between the banks’ reserve accounts.

Assume Bank B’s loan book was maxed out relative to its capital (requirements). Assume it starts with only required reserves. It now has ca. $900K in excess reserves.

Bank B could leave the money sit as excess reserves and (these days) collect .25% interest on them. It could lend the reserves to other banks. It could (I think?) trade the excess reserves for government bonds, with other banks or the Fed.

Could it trade the excess reserves (at zero or more removes) for Apple stock?

And here’s the key question: would any of these reserve-transformation/swapping methods (or others — I haven’t even touched repo, which I don’t really understand) allow it to lend out the $900K to a business or individual? A loan that it could not have made absent my deposit (without acquiring new capital/equity investment)?

@wh10 “Did you really think he believed otherwise, based on all his blogs and papers? ”

Not to mention his textbook.

@Asymptosis

Fullwiler or JKH could prob give the best answer to this. Here are my novice thoughts. I think that fundamentally the bank needs to increase its capital. If over time it can generate retained earnings off of the new deposit, either by earning .25% by holding them, lending them to another bank, buying govt bonds etc, then that would add to its capital and increase the bank’s lending capacity. Not sure about the Apple Stock, but if anything that would first increase the bank’s risk weighted assets and thus capital requirements before increasing the bank’s capital.

Oh and BTW, every comment on PK’s latest mysticism post points out that he’s wrong.

Every. Single. One.

I wonder if he’ll listen.

@Asymptosis

Yeah it’s quite astounding. Is really indicative of the support Post-Keynesian economics has been garnering over the past couple years. I doubt you’d ever see anything like this before the crisis. A storm seems to be brewing.

@Asymptosis

Banks are regulated by regulators and self-regulated so they don’t buy stocks.

Of course, because of deregulation, banks have had proprietary trading desks who may also trade equities but things are back to more regulation now.

In the United States, banks hold less government bonds and hold more of agency debt and agency MBS plus some other securities such as marketable and non-marketable debt of other banks.

In other countries, where securitization is less popular, banks hold higher proportion of government debt than the United States.

In some developing countries the central bank may impose liquidity ratios on banks where they have to hold higher government debt, for example.

Needless to say, the bank which has lost deposits in your example will be competitive and will try to attract back the funds lost.

@Ramanan

But Ramaman, can a bank or its trading desks use reserves to buy assets? I was under the impression reserves can only be lent b/w banks or the Fed, perhaps in exchange for govt bonds, or withdrawn.

And I’m still wondering: there’s really no way that $900K, in the situation I described, can be lent to businesses or individuals?

@Ramanan “Of course, because of deregulation, banks have had proprietary trading desks who may also trade equities but things are back to more regulation now.”

So yes a bank with a proprietary trading desk could use the $900K in excess reserves to buy apple stock?

@wh10

The reserve movement is a consequence of an activity.

Suppose intraday the bank is negative reserves – i.e., on daylight overdraft. What it purchased yesterday and settling today (assuming a settlement of “T+1”), will go through without interruption generally.

Banks aren’t constrained by reserves because they can get it anytime from the central bank via the discount window/marginal lending facility. The only constraint as far as reserves is concerned is the amount of collateral they have to provide to the central bank and the ability of borrowing back reserves.

Of course, banks shouldn’t be looked at as asset allocators. Most of bank activity is loan making. Over time, while banks’ capital is increasing, they are acquiring other assets.

@ Steve

“…This is true if you look at the economy through the lens of a three-sector model — private, government, external…”

This is true if you look at the economy as a closed system from the point of view of the domestic private sector assuming a balanced budget and a balanced trade deficit.

Consider also for clarity that my claim was made regarding accumulation of financial wealth only, that is nominal wealth in dollars or dollar-denominated financial assets. If I gave a different impression I apologize.

Under these conditions any agent or group that accumulates net financial wealth does so at the expense of another agent or group in the closed system. So from this perspective the “household sector” could amass financial wealth as a group but an equal off-setting loss would have to be suffered by another agent or group for it to be mathematically possible.

I assume that is what you mean by this:

“But if you de-consolidate private into firms and households, you get a different picture. Through production and the realization of its monetary value through surplus from trade (along with the issuance and market-value increases of household equity claims on firms), you can see wealth increasing — certainly in “real†terms (we have more real stuff per person), and also in financial terms — households’ equity and credit claims against firms. *Gross* financial assets increase, and households’ net financial assets increase, counterbalanced by firms’ right-hand-side “shareholders’ equity.â€

I notice that this in your statement above at #44…

“…realization of its monetary value through surplus from trade…”

…which is outside the boundary conditions set re my argument.

That said, we aren’t likely to have an external surplus any time in the near future but if we did, the dollars accumulated as a result in the domestic non-government would still be the result of net government spending that occurred in previous years. Net government spending that enabled us to buy foreign goods, Net government spending that would eventually come back to us in an external surplus scenario.

I have made no claims regarding “real or gross gains, only those gains that have been monetized as dollar or dollar-denominated financial wealth.

Real gains in wealth that have not been monetized, i.e. realized as nominal wealth through a transaction are paper gains and not as dollar or dollar-denominated financial asset accumulation.

I continue to make this point so that I don’t mis-interpret what JKH or Ramanan have said in the past about “net saving” and the conditions under which it can occur, which I must assume is compatible with my position because the math demands it.

I consider “net saving” to mean dollars or dollar-denominated financial assets only (nominal wealth) in excess of dollar liabilities in the aggregate. Otherwise we are using different definitions of “net saving” and in the future I will always make it clear that I am talking in terms of nominal wealth only. Accumulation of real or paper wealth is not a part of my argument.

Good question. I need an answer, too. I see people say ‘reserves create deposits’ and explain that the bank makes a loan first, and then scurries around to get the reserves it needs. But if the bank already has the reserves (that $900K you mention) then it seems the bank doesn’t need to scurry. That part is always left out.

Makes sense to me the bank could keep only 90K in reserve and lend out the rest of the 900K. And only if the loan was for more than 810K would the banker scurry for more reserves.

That’s the only way it makes sense to me, sort of combining the MMT version with the version MMT rejects.

Looking over some of the work of Mayer and Biggs , where Keen got the idea for his “credit accelerator” , might clarify things for some.

They look at how private sector credit flows relate to private sector demand (GDP) , where demand=consumption + investment. This article has links to a couple of their papers :

http://voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/5038

What I don’t quite understand is why both Keen’s and Mayer/Biggs’ focus is on private sector debt. The issue of the day , it seems to me , is the way consolidated public / private sector debt to GDP levels have grown for the last few decades , after having been relatively stable for several decades prior , when growth was as good or better.

The back-and-forth continues :

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2012/04/02/ptolemaic-economics-in-the-age-of-einstein/

Will Krugman keep digging , or cut his losses ?

Posted this at WCI and reposting here:

Paul Krugman appeals to the great James Tobin here

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/04/01/tobin-brainard-1963/

Krugman: “Bank loan officers can’t just issue checks out of thin air; like employees of any financial intermediary, they must buy assets with funds they have on hand.”

Tobin: Commercial Bank: as Creators of “Moneyâ€

http://dido.econ.yale.edu/P/cm/m21/m21-01.pdf

I guess Krugman’s appeal to authority failed miserably 🙂

Paul Kasriel renounced his belief in “monetarism” in favor of “creditism ” in this paper , noting how much things have changed over the years ( and dramatically so since Tobin’s paper of 1963 that PK is grasping at for support ) :

http://www.northerntrust.com/popups/popup_noprint.html?http://web-xp2a-pws.ntrs.com/content//media/attachment/data/econ_research/1009/document/ec090110.pdf

Here the IMF shows how the ratio of loans to deposits rose abruptly across the OECD in the years leading up to the crisis , just as they did prior to the Asian and Nordic crises ( Figs. 2 & 3 ) :

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10265.pdf

The increasing ratio tells me that the new loans facilitated the increase in deposits , not the other way around , and deposits failed to keep pace with loan formation.

@Ramanan

who is this zanon?

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=5893

amazing

@The Arthurian

The argument is about causation. One claim is that reserves cause lending, and deposits lead to reserves, so deposits cause lending. Deposits > reserves > loans.

The other claims is that demand causes lending and reserves are required to clear (after netting), so reserve management is separate and in fact handled by separate departments in a bank. Loans >deposits > reserves.

Reserves are a necessary condition for settlement in excess of netting and cash transactions (although banks get cash by exchanging reserves). Reserves are neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for lending.

Obtaining reserves for settlement is an expense for the bank. The bank will manage its expenses to reduce costs. Banks will alway extend credit where it is profitable and they can always obtain reserves if needed. What changes is is the cost. There is no quantity of reserve constraint, and quantity of reserves doesn’t induce lending either.

@studentee

That is a great thread, studentee. Anon and Zanon bury SS. Zanon was really on the rampage there. There is a nice comment by Marshall Auerback, too.

Ha ha, Zanon, Tom Hickey’s nemesis and the pride of California (or did he retire to Idaho, I forget), he’s been on Mosler’s board for ages. For some reason Tom drove him up the wall (he may still do) and he wasn’t shy about saying so.

@beowulf

Actually, Zanon and I agreed about MMT, but he hated my lefty leanings. He is a smart guy, and I always enjoyed our diatribes.

@JKH I’ve never seen anything impressive from Krugman. Can anyone tell me anything clever that he’s ever said or done? Every day I read 10 articles on economics, and I’ve never seen a reference to something Krugman said with regard to Economics that was useful or in any way incisive. He’s more of a political factor, as far as I can tell.

But JKH, Beowulf, and Cullen Roche seem to think he’s some sort of genius. Why?

We never got an answer to asymptosis’s question about the bank receiving a $1,000,000 deposit, did we?

I’m interested in the answer to that also. My understanding is that reserves are capital. (See definition of Tier 1 capital, for example.) So a bank that takes in a $1 million deposit has increased its capital by $1 million, and therefore can expand its liabilities by some multiple of that amount.

@Detroit Dan

Thank you Dan! I’ve been meaning to ping about this myself.

Looking, it seems that “disclosed reserves” are included in Tier 1 capital, but this terms seems to have a totally different meaning from “reserves held at that Fed.”

But the question’s still out there:

“And I’m still wondering: there’s really no way that that $900K, in the situation I described, can be lent to businesses or individuals?”

Understand: I’m not trying to re-institute loanable funds here. Don’t be afraid to answer this in a way that seems to validate that notion. I think I have an explanation that solves that. But I really need to understand the answer to my question before I bruit that explanation.

Interesting. Thanks.

I’m looking forward to seeing further discussion of your question.

This is one of my favorite sites, by the way, because you seem to be asking questions that are perfect for my level of understanding.

@Asymptosis

Looks to me like “reserves” in Tier 1 refers to capital reserves on the banks balance sheet, not rb.

@Dan & Asymptosis

I would posit that the term ‘reserves’ as it is used to describe central bank currency is a hold over from a gold-standard time when these kinds of reserved were actually the same thing as required retained earnings. These required reserves were deposited at the central bank (as liabilities of the central bank) where they were backed by gold (central bank assets). It was thus guaranteed that a certain percentage of deposits could be converted into gold at any one point in time – at the expense of the central bank’s balance sheet.

Things have changed since then. Both kinds of reserves remain on the same side of banks’ balance sheets (assets) and possibly count towards capital in an accounting sense (guessing that’s what ‘legal reserves is about?), but have come to depict completely different things in a business/risk sense. Central bank reserves are nothing more than clearing balances with whereas retained earnings are still retained earnings. Together with stock, they make up the capital base from which banks lever their operations. This point seems central to the endogenous money story as depicted by PKers – namely that lending is not reserve constrained.

On second thoughts, that doesn’t feel quite right.

On the open 1m deposit question: CB reserves are bank assets and are technically already lent to the CB, they cannot be lent again. But since they are used to settle bank-to-bank transactions, perhaps they could be used to purchase equities from another bank. In that case the reserve assets would be replaced by the equity assets and the bank would still have the 1m deposit liability.

The term ‘reserves’ in the Tier 1 definition is confusing because it refers to retained profits and is therefore an entry on the equity/liability side of a banks’ balance sheet. This is an entirely different animal and is used to meet the bank’s regulatory capital requirement.

Hope that helps.

[…] example: “I’ve read all the numbingly repetitive and identical explanations of capital-constrained […]