Capitalism concentrates wealth. Ridicule Marx and his latter-day disciples all you like (I’ll help); he definitely got that right.

But capitalism is a big word with lots of meanings, and enough ideological baggage to fill a Lear Jet. Let’s talk about something more precise: perfect markets, with ownership, in which individuals compete with others to produce stuff, and store up savings. You can see this kind of perfect world in agent-based simulations like Sugarscape. Start with a bunch of sugar farmers trying to accumulate sugar in an artificial world, hit Go, and watch what happens.

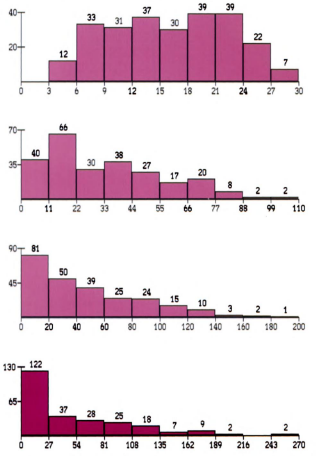

Here’s what happens to wealth concentration (number of poorer farmers on the left, richer on the right):

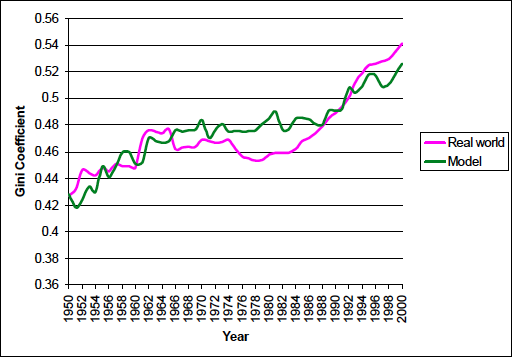

Wealth is pretty evenly distributed at the beginning (top). That doesn’t last long. You can see the same effect in another Sugarscape run, here compared to real-world wealth distributions:

That’s the Gini coefficient for wealth. Zero equals perfect equality; everyone has equal wealth. 1.0 equals perfect inequality; one person has all the wealth.

Perfect markets concentrate wealth. It’s their nature. But at some point, market-generated wealth concentration strangles those very markets (compared to markets with broader distributions of wealth). If a handful of people have all the wealth, how many iPhones will Apple sell? If only a few have the wealth to buy cars, automakers will produce a handful of million-dollar Bugattis, instead of forty handfuls of $25,000 Toyotas. Sounding familiar?

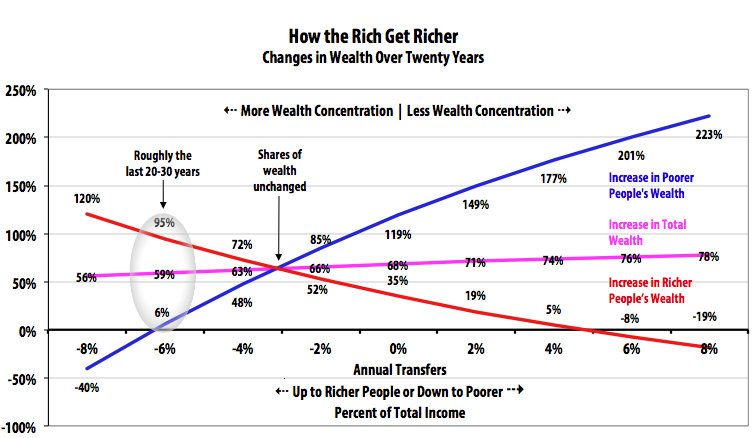

But wealth concentration doesn’t just strangle the flows of spending, production, and income. It throttles the accumulation of wealth itself. Another simple simulation of an expanding economy (details here) explains this:

The dynamics are straightforward here: poorer people spend a larger percentage of their income than richer people. So if less money is transferred to richer people (or more to poorer people), there’s more spending — so producers produce more (incentives matter), there’s more surplus from production, more income, more wealth…rinse and repeat.

This picture says nothing about how the wealth transfers happen (favored tax rates on ownership income, transfers to poorer and older folks, free public schools, Wall Street predation, the list is endless). It just shows the results: As wealth is transferred up to the rich, on the left, and wealth concentration increases, our total wealth increases more slowly. When that transfer is extreme, even in this growing economy the poorer people end up with less wealth. (Note how the curves get steeper on the left.) As wealth concentration declines on the right, our total wealth increases faster, and poorer people’s wealth increases much faster. Note that richer people still get richer in most scenarios — it’s a growing economy, always delivering a surplus from production, and increasing wealth — just more slowly.

And that’s just talking dollars. If we start thinking about our collective “utility,” or well-being — the total of everybody’s well-being, all summed up — the effects of wealth concentration are even more profound. Because poorer people getting more does a lot more for their well-being than richer people getting more. (Likewise, even if the richer people actually lose some of their wealth, they’re not losing as much utility.)

Because: Declining marginal utility of wealth (or consumption, or whatever). This is one of those Econ 101 psychological truisms that seems to actually be true. The fourth ice-cream cone (or Bugatti, or iPhone) just doesn’t deliver as much utility as the first one. Plus, a Bugatti in one person’s hands doesn’t deliver as much utility as forty Toyotas in forty people’s hands. (Prattle on all you want about relative and revealed preferences; you won’t alter this reality.)

So if we were to re-work the chart above showing utility instead of dollars, you’d see far greater increases in utility on the right side, especially for poorer people. Widespread prosperity both causes and is greater prosperity.

Why, then, aren’t we spending our lives on the right side of this chart? It’s a total win-win, right? The answer is not far to find. Nassim Taleb shows with some impressive math (PDF) what’s also easy to see with some arithmetic on the back of an envelope: if a few richer people (who dominate our government, financial system, and economy) have the choice between making our collective pie bigger or just grabbing a bigger slice, grabbing the bigger slice is the hands-down winner.

That’s why decades of Innovative Financial Engineering has served, mostly, not to efficiently allocate resources to efficient producers, improve productivity, or increase production. Rather, these fiendishly clever entrepreneurial inventions control who gets the income from production. You can guess who wins that game. Top wealth-holders would be nuts to play it any other way (if you go with economists’ definition of rationality…).

But for the rest of us, it’s a loser’s game — at least compared to the world we could be living in. If household incomes had increased along with GDP, productivity, and other economic-growth measures for the last two or four decades, a typical household would have tens of thousands of dollars more to spend each year — and much bigger stores of wealth to draw on. If you think that sounds like a thriving, prosperous society…you’re right.

To summarize: perfect markets, left to their own devices, concentrate wealth. Concentrated wealth results in less wealth, and far less collective well-being. (You’ll notice that I haven’t even mentioned fairness. It matters. But I’ll leave that to my gentle readers.)

This all leads one to wonder: how could we move ourselves into that happy world of rapidly increasing wealth and well-being on the right side of the graph? Hmmmm….

Cross-posted at Evonomics.

Comments

5 responses to “How Perfect Markets Concentrate Wealth and Strangle Growth and Prosperity”

Steve,

As for winners and losers in the game of financial capitalism, I think we should not be surprised to find it results in the concentration of profit, since the game was invented for that very purpose.

Jada

Here’s my take:

file:///C:/Users/Jada%20Thacker/Documents/2016%20Paper/Free%20Beer%20Tomorrow.pdf

Steve,

Addendum: I once presented a paper on the “illusion” of profit, in which I emphasized that all profit exists as an un-accounted-for subsidy. A computer programmer came up after the talk to tell me he had been writing computer code for 40+ years, and that his specialty was writing “emergent” economic programs that evolve without further inputs. He said that he had never been able to include “profit” in a sustainable economic model: any model that allowed “profit” always crashed with the accumulation of all the money into a few hands.

Not that I claim to know anything about computer modeling. Just sayin’…

Jada

@Jada Thacker: “we should not be surprised to find it results in the concentration of profit, since the game was invented for that very purpose.”

True dat. But the key point here is that the phenomenon emerges naturally from the system, even without any intentional design of the system toward that end.

Your link points to a file on your hard disk, which I’m sorry to say I’m unable to access… 😉

Thanks,

Steve

I remember looking at Saez and Piketty data way back in 2003 or 2004, how it builds and builds and then CRASH, and then starts building again, and thinking, “That looks like something generated by an agent-based model.” If it take money to make money that’s what you’ll always wind up with.

@chrismealy But we are able to manage, for instance, animal populations so that they don’t expand then crash…

But that would require central planning.