Yesterday, I (I hope) drove a final stake into the heart of the myth that small government creates national prosperity. I hope I also brought some backwards progressives to understand that the conservatives are right in one regard: economic growth has been the main engine that has made the poor–and everyone else–much better off by any number of measures.

Today I’d like to look at another conservative demi-canard: inequality and growth.

The conservatives’ basic argument: in a perfectly egalitarian society, where everyone is guaranteed an identical income/standard of living, there’s no monetary incentive for people to work, innovate, get educated, take risks, and do other such things that contribute to the general growth in prosperity. Obviously (to progressives at least), people do these things for reasons other than money. But the argument, while weakened, still stands up quite firmly.

There are a lot of countervailing arguments. For instance, if inequality is too great, people at the bottom and in the middle won’t see a real chance to move up, so they’ll give up. In either case, incentives matter.

But all these arguments are theoretical (and more frequently than not, ideological and moralistic). And they’re often arguments of degree that are pointless absent data: what level of inequality are we talking about–none, total, or some actual point in between?

I was curious to look at the data, and see what’s actually true out there in the world. As in my previous posts, I’m looking mainly at developed, affluent countries like the U.S., for indicators of what does/can/might work well in the U.S.

The key questions: Does inequality correlate with economic growth? Can we have equality without sacrificing growth?

The short answer: in less-developed countries, equality and growth move together, with a pretty strong correlation. Less-equal countries grow significantly more slowly. In developed countries, inequality and growth move together–but with a much smaller correlation. Less-equal countries move toward prosperity somewhat faster than more egalitarian countries.

Implications and discussion below. First, how do we know this?

Economists have done dozens of studies of this very question over past decades. A 2006 study, “Growth and Inequality: A Meta-Analysis,†reviews and analyzes 22 of those studies, and 254 data conclusions presented in those studies. Before looking at that analysis though, I want to look at one very well-regarded study–Robert Barro’s “Inequality, Growth, and Investment.†(Barro, a Harvard economist, is the world’s #2-ranked economist by number of citations, and has done several of the most authoritative empirical studies of national growth and what causes it.)

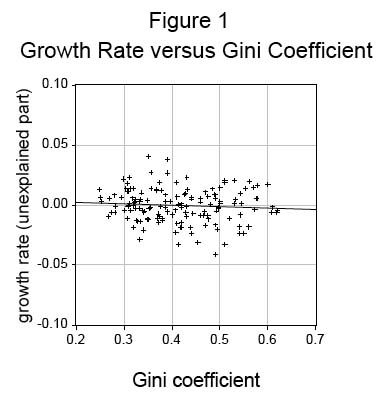

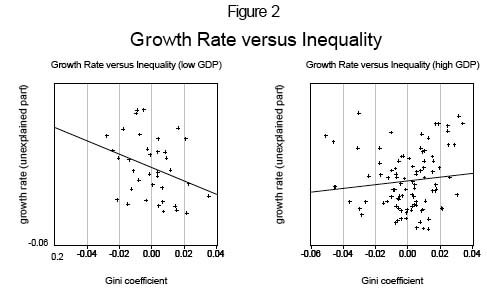

I want to show three graphs from Barro’s study, because 1) they capture at a glance the reality of equality versus growth, and 2) they agree completely with the 2006 meta-analysis.

For all countries studied, there’s not much correlation between equality and growth. (A high GINI coefficient means higher inequality.)

But the picture’s very different if you look at rich countries versus poor countries:

In richer countries, inequality does in fact correlate with faster growth (though not all that much). The meta-analysis agrees:

In accordance with Barro (2000), we found that the correlation between growth and income inequality is different in rich countries as compared to poor countries. The negative impact of an uneven distribution of income is higher in less developed countries.

Note to the more wild-eyed brand of conservatives: this does not mean that more inequality is always better. These studies looked at actual countries, where inequality fell within a fairly narrow range. Turn the dial to 11–as we’ve arguably been moving towards in the past seven years–and you’ll see very different results.

Nevertheless, this is a hard truth that American progressives will have to accept and deal with rationally. Some programs that enhance equality will counteract their own effects (to a greater or lesser degree) by reducing overall prosperity over the long haul. It may still be worth doing–it can take a long time for a .2-percent acceleration in GDP growth to raise the poor out of poverty. But pretending that the tradeoff doesn’t exist is not in anyone’s best interest, long-term–including the very people progressives most want to help.

Which equality measures contribute to or put a drag on growth? Means-tested transfers (if you make less money you get more money) appear to be among the worst offenders against long-term prosperity.

The good news: there are many types of programs that look like win-win solutions, both short- and long-term. Yes, they do exist. (The shallow slope of the trend line for developed countries suggests that this would be so.) Not surprisingly, education subsidies top most economists’ lists of Good Things To Do. The Earned Income Tax Credit–which incidentally was created and championed by Milton Friedman, the latter-day uber-god of free-market capitalism–also looks like a both-ways winner, quite possibly meriting expansion.

In some of my future posts I’ll be looking more and more closely at these types of programs and initiatives, asking: which ones should we be turning our attention and resources to?

In other words, where’s the low-hanging fruit?

Comments

One response to “Equality and Prosperity: Can We Have Both?”

[…] does this extreme inequality also slow long-term growth? The econometrics I’ve seen suggest a small positive correlation–barely or not statistically significant–between inequality […]