In 2013, economists Alan Blinder and Mark Watson — no wild-eyed liberals, they — asked a very important question: Why has the U.S. economy performed better under Democratic than Republican presidents, “almost regardless of how one measures performance”?

Start with their “performed better” assertion: it’s uncontestable. While you can easily cherry-pick brief periods and economic measures that show superior economic performance under Republicans, over any lengthy comparison period (say, 25 years or more), by pretty much any economic measure, Democrats have outperformed Republicans for a century. Even Tyler Cowen, director of the Koch-brothers-funded libertarian/conservative Mercatus Center, stipulates to that fact without demur.

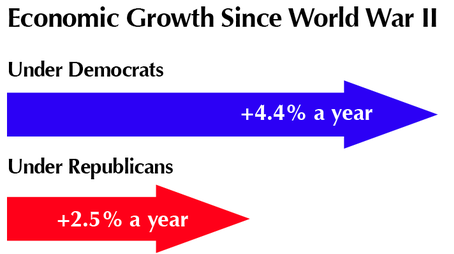

Here’s just one bald picture of that relative performance, showing a very basic measure, GDP growth:

The difference is big. At those rates, over thirty years your $50,000 income compounds up to $105,000 under Republicans, $182,000 under Democrats — 73% higher. (And this is all before even considering distribution — whether the growing prosperity is widely enjoyed, or narrowly concentrated.)

Hundreds of similar pictures are easily assembled — different time periods, different measures, aggregate and per-capita, inflation-adjusted or not — all telling the same general story. No amount of hand-waving, smoke-blowing, and definition-quibbling will alter that reality. (If you feel you must try to debunk Blinder, Watson, and Cowen: be aware that you almost certainly don’t have an original argument. Read the paper, and follow the footnotes. You’ll also find more here, here, here, here, here, and here.)

So what explains that superior performance? Blinder and Watson’s regression model basically says, “we dunno.” Their model, for whatever it’s worth, rules out a whole slew of possibilities — only finding a significant correlation with oil price shocks (uh…okay…) and Total Factor Productivity (the black-box residual economic measure that’s left when the other growth factors economists can think of are accounted for in their models).

Standing empty-handed after all their work, Blinder and Watson punt. They attribute Democrats’ consistently superior performance to…luck. Yes, really.

On its face, the bare fact of Democrats’ consistent outperformance suggests a straightforward explanation: Democrat policies and priorities, in their myriad interacting forms, expressions, and implementations, directly cause faster growth, more progress, greater and more widespread prosperity. (Blinder and Watson pooh-pooh this idea, simply because they don’t find short-term correlation with the rather bare measure of government deficit spending.)

So the question remains: what could it be about the Democratic economic policy mix that delivers superior performance? Here are eight possibilities:

1. Wisdom of the Crowds. Democrats’ dispersed government spending — education, health care, infrastructure, social support — puts money (hence power) in the hands of individuals, instead of delivering concentrated streams to big entities like defense, finance, and business. Those individuals’ free choices on where to spend the money allocate resources where they’re most valuable — to truly productive industries that deliver goods that humans actually want.

2. Preventing Government “Capture.” Money that goes to millions of individuals is much harder for powerful players to “capture,” so it is much less likely to be used to then “capture” government via political donations, sweetheart deals, and crony capitalism.

3. Labor Market Flexibility. When people feel confident that they and their families won’t end up on the streets — they know that their children will have health care, a good education, and a decent safety net if the worst happens — they feel free to move to a different job that better fits their talents — better allocating labor resources. “Labor market flexibility” often suggests the employers’ freedom to hire and (especially) fire, but the freedom of hundreds of millions of employees is far more profound, economically.

4. Freedom to Innovate. Individuals who are standing on that social springboard that Democratic policies provide — who have that stable platform of economic security beneath them — can do more than just shift jobs. They have the freedom to strike out on their own and develop the kind of innovative, entrepreneurial ventures that drive long-term growth and prosperity (and personal freedom and satisfaction) — without worrying that their children will suffer if the risk goes wrong. Give ten, twenty, or thirty million more Americans a place to stand, and they’ll move the world.

5. Profitable Investments in Long-Term Growth. From education to infrastructure to scientific research, Democratic priorities deliver money to projects that free market don’t support on their own, and that have been thoroughly demonstrated to pay off many times over in widespread public prosperity.

6. Power to the Producers. The dispersal of income and wealth under Democratic policies provides the widespread demand (read: sales) that producers need to succeed, to expand, and to take risks on innovative new ventures. Rather than assuming that government knows best and giving money directly to businesses (or cutting their taxes), Democratic policies trust the markets to direct that money to the most productive producers.

7. Fiscal Prudence. True conservatives pay their bills. From the 35 years of declining debt after World War II (until 1982), to the years of budget surpluses and declining debt under Bill Clinton, to the radical shrinking of the budget deficit under Obama, Democratic policies demonstrate which party merits the name “fiscal conservatives.”

8. Labor and Trade Efficiencies. The social support programs that Democrats champion — if they truly provide an adequate level of support and income — give policy makers much more freedom to put in place what are otherwise draconian, but arguably efficient, trade and labor policies. If everyone can confidently rely on a decent income, we have less need for the sometimes economically constricting effects of unions and trade protectionism.

To go back to Blinder and Watson’s “luck” explanation: A non-economist might suggest that “to a great extent, you make your own luck.” And: “hire the lucky.”

Cross-posted at Evonomics.