I don’t usually link to Paul Krugman because everyone reads him anyway, right? He doesn’t need my google juice.

But I have to make an exception here because he adds to my trove of graphs demonstrating how America today — after thirty years of Reaganomics policies that were supposed to be all about freedom, liberty, and economic opportunity for all (yeah, and I have a bridge for sale), is at the bottom of the heap when it comes to economic opportunity.

The shining city on the hill keeps getting smaller and richer, and the slopes leading up to it steeper, rougher, and slicker.

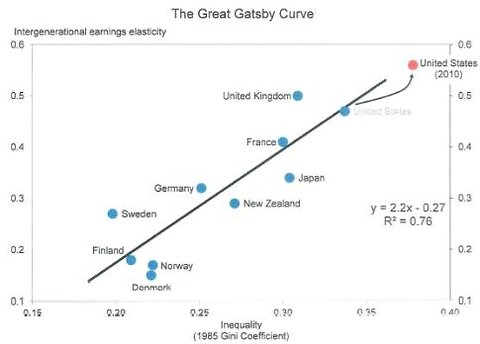

That opportunity is best displayed through intergenerational mobility — what my friend Steve calls “convection.” What are the odds that a child will be in a different economic stratum from his parents? It’s a darned good measure of “meritocracy.”

Here’s the key graphic:

On the vertical axis is the intergenerational elasticity of income — how much a 1 percent rise in your father’s income affects your expected income; the higher this number, the lower is social mobility.

As you can see, it’s only getting worse. My explanation is here.

The Great Gatsby Curve – NYTimes.com.

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

5 responses to “American Exceptionalism #238: Opportunity (Not)”

This morning Tyler Cowen pushed back at the idea we need all that ‘mobility’ and got a little pushback from his commenters! As for me, I equate physical mobility with the mobility of income, the two go together for a reason. I think it matters a little what part of the country and what timeframe, for generational mobility. Yesterday Mom and Dad (Dad’s 90) were talking about how much everyone was moving around when they were young. Texas was a high action place to be in the 50s. As for myself I had the same mobility bug that Grandpa had. Forgive a little palmistry humor here, I’ve got ‘angry’ travel lines in both hands from not traveling enough.

@Becky Hargrove

Hmmm. I don’t think the two have a terribly coherent or tight relationship, just because they both have the word “mobility” in them. I could certainly be wrong but that’s my intuitive take.

Both the Gini coefficient and economic mobility measures have several statistical problems associated with them which makes a naive comparison between countries or regions difficult. They can still be useful, but one cannot take the top line numbers at face value.

For example:

The Gini will be highly skewed if no attempt is made to account for cost of living. For example, among the states, New York has the highest state coefficient. However, this is not surprising when you take into account the huge differences in CoL and incomes between NYC and the rest of the state.

Economic mobility is heavily influenced by income variance and range. Moving between quintiles requires greater absolute jumps in income in a country with a large range and variance than a country with a smaller range and variance.

@Chris T

One other issue – The way income is measured between countries often differs. The United States, for example, does not include benefits in measures of income.

@Chris: Thanks. I’ll adjust my future priors somewhat less based on that. 😉 But sources for my prior priors are at least unanimous in finding the effect seen here. So I’m believing that is real. They also universally show rather large degree differences, so I tend to believe that too.