There’s great discussion out there on this topic, see Steve Randy Waldman’s links list here.

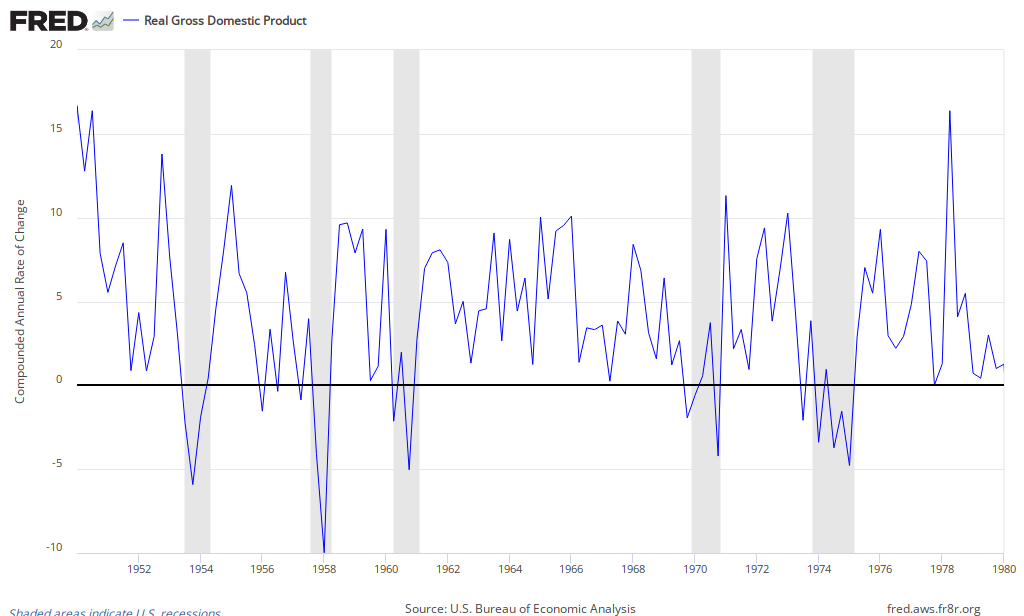

Karl Smith gives us this graph and asks:

I mean, honestly, would you look at the graph above and conclude that during the 1970s the economy dangerously overheated.

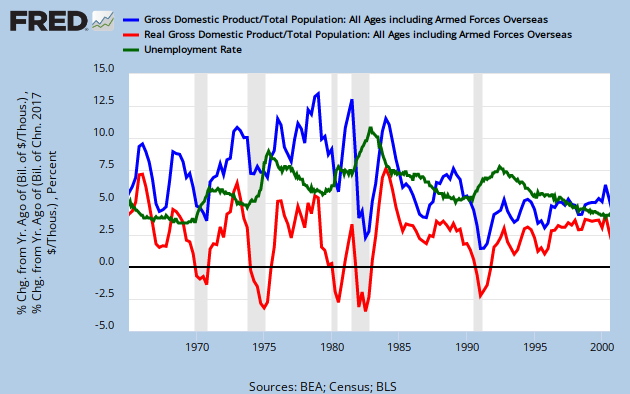

I’d like to offer a perhaps more useful (though more complicated) look. Here’s NGDP/capita, RGDP/capita, and the Civilian Unemployment Rate (the NGDP/RGDP gap is accounted for by inflation):

Here’s a story to match that:

In the late 70s, Arthur Burns managed to drive down unemployment even in the face of a historically monumental labor-force surge, while maintaining healthy RGDP growth — but at the cost of high inflation. (The famous unemployment surge arose after two years of NGDP/RGDP declines ’78-’80, and briefly held steady during the ’80/’81 GDP surge.)

The “cost” of that inflation? A massive transfer of real buying power share from creditors/holders of financial assets to debtors/holders of real assets (assets such as…the skills and ability to work). Think: Workers’ relative claims to a share of the future production pie. Don’t even start to talk to me about the trivial effects of “menu costs” and such relative to this huge and inexorably arithmetic “textbook” effect.

Monetarists dismissing Steve’s labor-surge effect seem to be claiming that the Phillips curve had shifted, and that tighter Fed policy (given the understandings and tools at the time) would not have increased the unemployment rate. Is that realistic?

Or: higher unemployment would have been acceptable to maintain and protect the relative buying-power of creditors/holders of financial assets.

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

14 responses to “More on the Labor Force Surge and 70s Stagflation”

[…] Cross-posted at Asymptosis. […]

[…] Cross-posted at Asymptosis. […]

Well, this has been an interesting 20 minutes. I looked at your post describing an “aha moment” based upon Interfluidity’s post about labor force expansion in the 1970s. Then I went to Interfluidity and saw that the author had retracted his theory. Then I scanned through the comments and saw Mark Sadowski apparently concluding that all the disinflation around the world has been caused by tightening monetary policy (did I get that right?).

Good God– central banks control risk free interest rates and that’s about it. Globalization and technology are the drivers and central banks just try to keep interest rates about the same as inflation. 20 minutes of my life that I’ll never get back — sucked up by the vacuum of monetary nonsense.

Steve– Can you give a succinct summary of what you’ve learned from this whole episode?

Thanks. Overall, I very much value your economic commentary…

@Detroit Dan “saw that the author had retracted his theory”

No, read again. He just retracted those first country graphs he made cause the data was bad, very much not retracting his theory.

[…] Steve Roth — More on the Labor Force Surge and 70s Stagflation […]

Well here’s what he said: “This renders much of my discussion, which was based on the flawed graphs, essentially bullshit.”

I almost always agree with you, but just don’t see anything here. Can you give a succinct summary of what you’ve learned from this whole episode?

Thanks again…

@Detroit Dan “This renders much of my discussion, which was based on the flawed graphs, essentially bullshit.â€

He was referring to the discussion of the international graphs, and said right there:

“Can you give a succinct summary of what you’ve learned from this whole episode”?

Best summarized I think by my response to Mark Sadowski over at AB:

http://angrybearblog.com/2013/09/more-on-the-labor-force-surge-and-70s-stagflation.html#comment-314592

[…] in the blogosphere. See Kevin Erdman, Edward Lambert [1, 2, 3], Marcus Nunes [1, 2], Steve Roth [1,2], Mike Sax, Karl Smith [1, 2, 3], Evan Soltas, and Scott Sumner [1, 2], as well as a related post […]

Thanks! I asked for a succinct summary and got it.

It seems to me the whole conversation is framed in a monetarist perspective, which I find unrealistic. The Fed only controls risk free interest rates (of the shortest duration, until QE). That’s all they control. They do not control inflation or unemployment. Interest rates have a small impact upon inflation and unemployment. In practice, the Fed almost always tracks inflation, adjusting rates up or down in response to the latest data on inflation and unemployment.

Getting back to the 1970s, here’s what I getting from this conversation:

There was a surge in the labor force which would normally cause wages to go down (unless it was accompanied by demand stimulus of some sort). Due to wage stickiness, wages didn’t go down and instead unemployment went up. INSERT THINGS I DON’T UNDERSTAND HERE. Then we had inflation.

What am I missing? What caused the inflation? High unemployment? Thanks. My thoughts here are half baked but I’ve gotta run now.

Thanks again…

Here’s a graph of inflation and interest rates over the past 60+ years — Inflation Rate vs 3-Month T-Bill Rate. For the 1970s, it shows inflation spiking twice, corresponding almost exactly to the two oil shocks that decade.

Interest rates are positively correlated with inflation (inflation and interest rates go up and down together). This fits my understanding that various supply and demand factors affect inflation and that the Fed adjusts interest rates to match the inflation rate.

So the theory that the high inflation was caused by the Fed reacting to high unemployment seems wrong to me. I don’t see that in the data and I don’t see any plausible transmission mechanism. In fact, the Fed raised interest rates throughout most of the 1970s, which should have reduced rather than increased inflation according to the theory of the monetarists. Something else was driving the inflation, and it’s blindingly obvious that the oil price spikes and associated Middle East turmoil were huge factors…

@Detroit Dan

Seems to me it’s sort of like this:

What caused the changes in relative humidity?

The temperature went up, which brought it down, but it also caused more evaporation, which brought it up. What caused what?

>the Fed raised interest rates throughout most of the 1970s, which should have reduced rather than increased inflation

Always gotta ask: relative to what counterfactual?

>oil price spikes and associated Middle East turmoil were huge factors

And the labor force surge was another.

If I understand correctly, you are claiming that the labor force surge contributed to inflation by inhibiting the Fed from raising interest rates more than they would have otherwise. That line of reasoning assumes that the Fed can and should control inflation by adjusting interest rates.

I don’t doubt that the Fed can have a short term impact on inflation by adjusting interest rates, but it is just short term and relatively insignificant in the long term in my opinion. The fundamentals — including demographics, globalization, technology, energy supplies — are much more important. So I agree with you in looking to demographics as a possible source of macroeconomic fundamentals. But I disagree that the primary impact of such a fundamental demographic is how it affects Fed policy. That is attributing too much to the impact of short term risk free interest rates, and not enough to the other more fundamental forces such as hose mentioned above…

To summarize: You are claiming that the labor force surge => high unemployment => lower interest rates than there would be otherwise => inflation.

By this logic, anything that increases unemployment will also increase inflation. This is obviously 180 degrees backward (high unemployment => lower wages => less inflation).

Am I missing something?

Even if wages are sticky in the face of rising unemployment, the impetus is still down rather than up.