Update 5/21: See two updates to this post here.

Mark Dow had a great post the other day:

There is zero correlation between the Fed printing and the money supply. Deal with it.

He points out (emphasis mine):

From 1981 to 2006 total credit assets held by US financial institutions grew by $32.3 trillion (744%). How much do you think bank reserves at the Federal Reserve grew by over that same period? They fell by $6.5 billion.

As he says:

if you are an investor, trader or economist, understanding–and I mean really understanding, not just recycling things you overheard on a trading desk or recall from econ 101–the mechanics of monetary policy should be at the top of your checklist. With the US, Japan, the UK and maybe soon Europe all with their pedals to the monetary metal, more hinges on understanding this now than ever before.

And, as we saw this week, even many of the Titans of finance and economics have it wrong.

He’s obviously been reading Manmohan Singh and Peter Stella (S&S) over at Vox EU, who cite the very same numbers and add:

In fact, total commercial bank reserves at the Federal Reserve amounted to only $18.7 billion in 2006, less than the corresponding amount, in nominal terms, held by banks in 1951.

S&S also point out (Table 1 and Figure 1) what we’ve known for decades but many seem unwilling to admit: since WWII, reserve levels have had approximately zero correlation with inflation/price levels.

They continue:

This suggests either that there is something wrong with:

- the theory of money neutrality;

- the theory of the money multiplier; or

- how money is measured.

Or, I would say, all of the above. I’d actually replace all three: there is something wrong with the (nonexistent) definition of “money.” But that’s another post.

I’m going to go even farther than Dow and say: the Fed is not printing money. (It can do that, but the result is stuff you can hold in your hand.) That’s a confusing and actually incoherent misconception. The Fed is issuing new reserves and exchanging them for bonds. Those bonds are effectively retired from the stock of assets circulating in the financial system (though perhaps only temporarily), as if they’d expired.

Reserves are not “money” in any useful sense. Or, they’re only money (whatever you mean by that word) within the Federal Reserve system. We probably just shouldn’t use the word at all here. It’s only confusing.

The key to understanding (and to avoid misunderstanding) this is to think about the banking system, not individual banks. The dynamics are totally different, because individual banks can affect their reserve positions (though under various market and regulatory constraints). The banking system can’t.

Because: Reserves only exist (can only exist) in banks’ accounts at the Federal Reserve Banks (and only members — banks plus GSEs and other large institutions like the IMF — can have accounts there). The banking system can’t remove reserves from the system by transferring them to the nonbank sector in exchange for bonds, drill presses, or toothpaste futures.

One bank can transfer reserves to the account of another entity with a Fed account, in exchange for bonds or whatever, but total reserves are (obviously) unchanged. And that exchange has no direct effect outside the Fed system. (That exchange can, does, have second-order, indirect, portfolio-rebalancing effects on the rest of the market. More below.)

And here’s the key thing: the banking system can’t lend reserves to nonbank customers by somehow transferring them to those customers’ deposit accounts (thereby reducing total reserves). They can’t “lend down” total reserves. The banking system doesn’t “take money” out of total reserves, or reduce those reserves, to fund loans.

This is why it’s so crazy to worry about those reserves eventually “flooding out into the real sector” in the form of new loans (and resultant spending), with all the hyperinflationary hysteria attached to that notion. (Equally: those reserves are not “unused cash” on the “sidelines” that the banks are “sitting on.” See Cullen Roche on this.) Reserves can’t leave the system, whether in a flood or a trickle. The banking system will lend (creating new deposits in its customers’ accounts out of thin air), if bankers think it will be profitable. But increased lending if anything forces the Fed to increase total reserves. Viz:

A bank issues a billion dollars in new loans, creating a billion dollars in deposits in its customers’ accounts. The borrowers spend the money by transferring it to sellers’ banks. When all the transactions net out at night at the Fed, the issuing bank is short on reserves that need to be transferred to the sellers’ banks (or sees that it will be short). So it borrows reserves from other banks. If reserves are tight, this pushes up the interbank lending rate. The Fed doesn’t want the interbank rate to increase, because it thinks interest rates are where they should be to fulfill its mandates. So it issues new reserves and trades them for banks’ bonds (which it retires, at least for the time being).

Short story: more lending increases total reserves. Slightly longer story: more lending forces the Fed to increase total reserves (or abandon its mandates).

In the current situation, of course, there’s no shortage of reserves. Banks are holding extraordinary quantities in excess of regulatory requirements. So the Fed instead controls the interbank lending rate within a corridor by setting the rate it pays on reserves (bottom) and the rate at which it will lend to banks (top). Read it all here from the FRBNY.

So how can the banking system reduce total reserves? Only in one significant way: by buying bonds from the Fed. Send some reserves over, and the Fed retires those, (re)issuing bonds in exchange. But of course the Fed isn’t selling these days; it’s buying.

Fed asset moves just issue and retire reserves and bonds. And those moves are purely at the discretion of the Fed (the Fed “enforces” this on the system by buying/selling at prices that individual banks will take up). So the Fed is in complete control of the level of total reserves. Again: there is no way for the banking system to turn existing reserves into deposits in its customers’ accounts. It can’t “lend down” total reserves.

When the Fed issues and retires bonds and reserves, it’s not “printing money,” so it’s not playing some kind of simplistic MV=PY game. It’s adjusting the balance of the banking system’s portfolio (“forcing” it to change exchange bonds for reserves) — and by extension, affecting the mutually interacting portfolio preferences of all market players (via interest-rate/yield-curve effects, and also, more psychologically, by imparting the optimistic notion that there’s adult supervision — that this frat party won’t turn into Animal House).

In other words, it’s a much deeper game than many monetarists would have you believe. It’s especially deep because neither the Fed nor the markets understand it properly. Certainly the Fed governors have strong disagreements about how it works. (Arguably, nobody understands, very much including me. There are many interacting understandings and reaction functions out there, many based on complete misunderstandings of the system dynamics. But I think we’re getting closer these days, with the slow but increasingly widespread and accelerating dismissal of silly notions like the money multiplier.)

Dow explains these portfolio effects and reaction functions very nicely:

…why is the Fed doing QE in the first place?

By keeping rates low well out the yield curve and providing comfort that the Fed will be there to fight the risk of recession and deflation…we start feeling better about putting our getting our money back out of the mattress and putting it back to work.

…it is the indirect psychological effects from Fed support and the low cost of capital–not the popularly imagined injection of Fed liquidity into stock markets–that have gotten investors to mobilize their idle cash from money market accounts, increase margin, and take financial risk. It is our money, not the Fed’s, that’s driving this rally. Ironically, if we all understood monetary policy better, the Fed’s policies would be working far less well. Thank God for small favors.

…

The other, more mechanical, implication is that financial sector lending is neither nourished nor constrained by base money growth. … The main determinant of credit growth, therefore, really just boils down to risk appetite: whether banks and shadow banks want to lend and whether others want to borrow. Do they feel secure in their wealth and their jobs? Do they see others around them making money? Do they see other banks gaining market share?

These questions drive money growth more than the interest rate and base money. And the fact that it is less about the price of money and more about the mental state of borrowers and lenders is something many people have a hard time wrapping their heads around–in large part because of what Econ 101 misguidedly taught us about the primacy of price, incentives and rational behavior.

I certainly make no claim to a deep understanding of those portfolio effects. (If I had such an understanding, I’d be far richer than I am.) But I do have some thoughts I’d like to share.

• When the Fed issues reserves and retires bonds, it’s 1. reducing the net flow of newly-issued (treasury and GSE-mortgage) bonds into the market, or even causing a net reduction. And if the latter is true, it’s 2. reducing the total stock of bonds available for trading in the market.

Since the flow of new bonds is obviously much smaller than the outstanding stock, you would expect flow effects of Fed actions to have much greater immediate influence on bond markets than stock effects.But it’s unclear what their long-term effects might be. A steady flow reduction, on the other hand, will eventually have cumulative effects on the total stock — again with uncertain future effects.

Jake Tepper, quoted in this post by Cullen Roche (read the comments too), gives us this:

…The fed is going to purchase $85 billion of treasuries and mortgages a month. So over 500 billion in six months…. the net issuance [by Treasury] versus refunding is a little over 100. That means we have 400 billion, 400 billion that has to be made up.

Whatever “made up” means. But Tepper’s also ignoring the Fed’s other big buys: mortgage-backed securities issued by government-sponsored enterprises (Fannie, Freddie). I would like to see as long a time series as possible of the following:

Net MBS issuance by GSEs (issuance – retirement)

Plus:

Net Treasury issuance (new issues – retirement)

Minus:

Net Fed â€retirementâ€

Also have to include Fed repos, I think? But maybe trivial over the long term.

In other words: net Net NET consolidated flow of new bond issuance to the private sector by Treasury, Fed, and the GSE gods.

Then: that measure as a percent of GDP? Of total Treasury/GSE bonds outstanding? Total Credit Market Debt Outstanding (TCMDO)? Other measures to compare it to?

• Contrary to what you often hear, even today when reserves and bonds are paying nearly equivalent interest rates, they are not equivalent assets. Because: bonds have expiration dates, and variable market prices/interest rates. So bonds carry market/interest-rate risk and reward for their holders — the potential for cap gains and losses. Reserves don’t.

As you can read in this must-read 2009 paper from the Bank of International Settlements, reserves are the Final Settlement Medium. They’re what it comes down to every night when all the day’s bank transactions are consolidated, netted out, transferred, and resolved. A dollar of reserves is always worth a dollar. There’s no possibility of capital gains or losses on reserve holdings. Reserves are inexorably nominal. (Even more so than $100 bills, which are worth less relative to reserves if they’re sitting in a Columbian drug-dealer’s suitcase.)

So when the Fed gives the banks reserves and retires bonds, it’s taking on market risk/reward, replacing it with absolutely nonvolatile, risk/reward-free assets (at least in nominal terms). It’s removing leverage and volatility from the banking system. (MMTers might well ask why our government system requires the injection of that volatility in the first place, when the Treasury could simply be issuing “dollar bills” with no expiration dates or interest payments, instead of treasury bills. [Or consols.] But that’s an aside.)

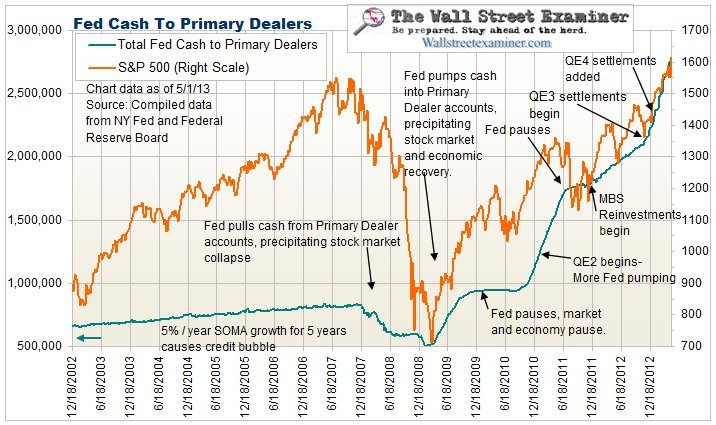

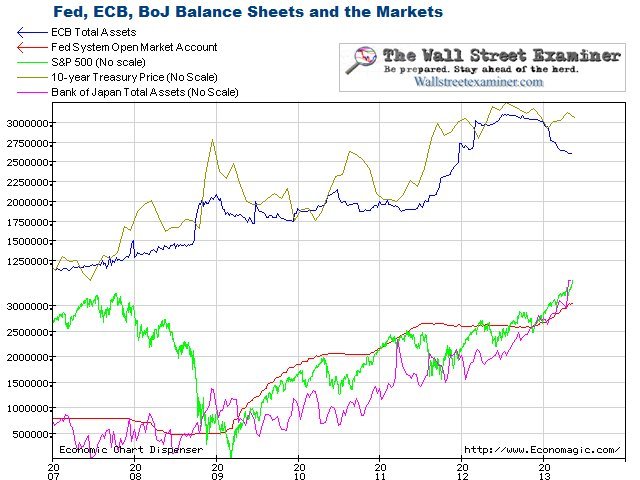

• I have to address notions like this one from Lee Adler, in a comment on Dow’s post:

The correlation between Fed and other central bank money printing with market behavior is clear and direct.

Yeah: while the Fed is on a bond-buying spree, it buoys bond prices and depresses yields. Especially when bond yields are historically low, market players shift their portfolio preferences from bonds to equities in a “reach for yield,” so equities go up too. (This presumably yields a wealth effect of [rich] people spending more — perhaps the only transmission mechanism to the real economy for Fed balance-sheet changes.)

This says exactly nothing about those balance-sheet moves as an impact on the stock of “money,” or inflation. It just says that while Fed asset purchases/sales are ongoing (and expected to continue), they will raise or lower the value of financial assets. It’s either orthagonal to Dow’s assertions, or in fact demonstrates exactly what he’s saying about psychological effects.

• It doesn’t make sense to say that the Fed is “monetizing” the debt (because reserves aren’t money). If you think in terms of consolidated Treasury/Fed net issuance/retirement of government bonds, it’s retiring debt — removing bonds from the market and absorbing them into the Treasury/Fed complex. The bonds still exist, of course, and the Treasury still pays interest — to the Fed, which kicks it right back to Treasury. But as far as the markets are concerned, those bonds are essentially dead and gone (at least for now).

It seems that the Fed could simply burn a whole pile of those bonds, no? It would have no effect on flows, aside from the rather pointless interest flows back and forth between Treasury and Fed. And it would only affect the stock of “dead” bonds — ones that have been retired into the Fed. (The notion’s been discussed by people as diverse as Ron Paul and Mervyn King — Paul with the misconception that this would be “declaring bankrupcy,” and King with the misapprehension that it would be “monetizing the debt.”)

• It’s not at all clear what the flow effect would once the had Fed stopped net-buying bonds, while Treasury and the GSEs continued issuing new bonds in excess of retirements. Financial asset prices might stay at their then current levels. Who knows.

• The question, of course, is whether the Fed will ever sell all those bonds back to the market (thereby reducing reserve holdings). The average maturity of the Fed’s bond holdings is >10 years, so they’ll naturally expire and disappear, but only slowly. We’ve entered a brave new monetary world, in which central banks exert themselves not just through reserve management/interbank lending rates, but through balance-sheet expansion and contraction. (See the two “schemes” in the BIS paper linked above.) I don’t know if anyone knows what to expect in that regard. The Fed’s certainly talking about reducing its bond purchases in the future, which will affect net bond flows into/from the market, but it’s not at all clear whether it will ever shrink its balance sheet to pre-crisis levels (in absolute terms or relative to other measures), thereby reducing banks’ reserve holdings to those earlier levels.

• The $10-trillion question: If the Fed did sell off all its bond holdings in an effort to get back those halcyon days when banks didn’t hold any excess reserves — so the Fed could control the interbank rate with small open-market operations — what in the hell would happen? Whether slowly or quickly, bond prices would fall as the sales continued, yields would rise (compared to a counterfactual in which the Fed wasn’t selling off their holdings). Markets would shift their portfolio preferences from stocks to bonds, so equity prices would fall along with bond prices. Disastre?

Again, I don’t think anybody knows.

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

69 responses to “The Fed is not “Printing Money.” It’s Retiring Bonds and Issuing Reserves.”

These things have to said in a right way rather than using slogans such as “there is zero correlation”.

When banks make loans the money supply rises and the Fed accommodates banks’ needs for more reserves. So there is a correlation. It is just that the causality is different.

Also, there is no need to claim reserves aren’t money. If you want to define money as any financial asset, then of course reserves is one type of money.

In standard terminology, reserves are included in calculation of monetary aggregates.

IMO, there isn’t any need to change standard terminologies at all to explain such things to people.

Steve: “Reserves are not “money†in any useful sense. Or, they’re only money (whatever you mean by that word) within the Federal Reserve system.”

…and Ramanan: “If you want to define money as any financial asset, then of course reserves is one type of money.”

My brain is too brittle to remember lots of new details, so I’m just asking for a clarification.

My understanding is that a bank can at any time withdraw its reserves as Federal Reserve Notes. A quick search for confirmation turned up newworldeconomics.com (I don’t know who they are) saying if a bank wanted to convert its Fed-registered bank reserves to paper money at any time, it could do so.

A lot of people don’t talk about that, but I’ve got it now from at least two sources.

Also the Type of Money table at Wikipedia lists three components of the monetary base:

1. Notes and coins in circulation

2. Notes and coins in bank vaults

3. Federal Reserve Bank credit [“reserves’]

To my mind these three MUST be interchangeable. Thus (again) reserves can at any time be withdrawn as Federal Reserve Notes. So to my mind reserves are Fed notes in a different form, i.e. after being deposited with the Fed.

So I have to think that reserves ARE money, just as Federal Reserve Notes are money.

There might have been more, but my brain is brittle.

Please clarify…

[…] Cross-posted at Asymptosis. […]

@Ramanan “there is zero correlationâ€.

Sed: between reserve levels and inflation. See S&S.

“When banks make loans the money supply rises and the Fed accommodates banks’ needs for more reserves. So there is a correlation.”

Reserves of depository institutions, 2007: ca $40 billion

M1, 2007: ca $1.3 trillion

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=isq

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=iss

@Ramanan

“Money supply” includes reserves. Definition.

So when reserves rise, money supply rises.

Tautological. Sez nothing.

@The Arthurian

Right. That’s the one other way banks (and their customers) can “drain reserves” in aggregate.

cf. this line and link, and the word “significant.”

“So how can the banking system reduce total reserves? _Only in one significant way_”

http://brown-blog-5.blogspot.com/2013/04/the-three-places-reserves-can-go.html

While customers might want to hold more cash (especially Columbian drug dealers), there’s no reason banks would, absent some very large interest-rate arbitrage opportunities. (i.e., reserves paying -2% interest?) Storage costs, etc. It’s damned hard to make a home loan in physical cash. Currency is pretty much a non-issue.

Very good post.

A couple of minor points:

“So it borrows reserves from other banks.â€

The blogosphere has a tendency to oversimplify this story. In fact, active and broad liability management that sources funds from non-banks is a far more important and fundamental activity than sourcing money from banks. Competitive non-bank funding redistributes reserves as much as bank funding.

“Short story: more lending increases total reserves.â€

Again, oversimplified. The entire system is far too liquid and asset-liability management far too active and sophisticated to make such a rule of thumb connection between lending and an injection of reserves by the Fed.

I have no problem at all referring to bank reserves as money. Whatever you call money, you have to be specific about the scope and the participants in the corresponding payment process. It’s referring to ‘money’ without specifying the precise context that gets you in trouble – and you always have to refer to the precise context.

@JKH “It’s referring to ‘money’ without specifying the precise context that gets you in trouble – and you always have to refer to the precise context.”

Agree. But this stricture is almost never adhered to, and really for good reason — a particular definition of money in a given sentence might require stating one or more assumptions, and etc. It’s just impossibly unwieldy. That’s why we have agreed-upon definitions! Unfortunately we don’t have one of those for “money.” Oughtta.

Absent that, you’re kinda screwed. To avoid being so, instead talk about particular financial assets and types of financial assets, or the traits/characteristics of particular financial assets and types of financial assets.

There’s not “demand for money” (whatever that means). There’s demand for financial assets that have a history of nominal stability relative to the unit of account, and easy, reliable exchangeability for other financial assets and real goods. Or: there’s demand for government bonds. Or highly rated bonds (less useful…) Or currency. Or…Fed reserves! Or similar.

It would be like physical scientists having to define “energy” every time they used it. There are surely situations where that’s still necessary — it’s not a simple concept, actually — but in most cases they can just say “energy” and everyone knows pretty much exactly what they mean.

@JKH “‘Short story: more lending increases total reserves.’ Again, oversimplified.â€

I should have emphasized the words “if anything” in the following:

“But increased lending if anything forces the Fed to increase total reserves.”

@Asymptosis

I don’t see it being a problem at all. Reserves are the money that banks use to settle with each other. Etc. You have to be specific.

Promiscuous generalization is not feasible in a complex world. Unless you’re a monetarist – in which case it is the essence of life support.

@JKH

e.g. distinguishing between a bank reserve balance at the Fed and a bank deposit liability as forms of money is as basic as distinguishing between the dollar and the yen as currencies – you have to be specific in all cases – and it doesn’t negate the fact that the former are both forms of money and the latter are both currencies

@Asymptosis

I know the data well.

Mark Dow: “There is zero correlation between the Fed printing and the money supply. Deal with it.”

Incorrect statement.

Zero correlation means there is absolutely no relation. Before 2007, the two increased together, so obviously there is a correlation.

Causality is a different matter.

But economics is a profession where one cannot stop people from making careless and incorrect statement.

@Asymptosis

My point was you said “Reserves are not “money†in any useful sense.” which is not true actually.

@The Arthurian

“My understanding is that a bank can at any time withdraw its reserves as Federal Reserve Notes.”

Yes right.

Even if the bank has low level of reserves, it can ask the Fed for cash notes by increased its indebtedness to the Fed.

In the post you repeatedly say things like:

“Reserves are not ‘money’ in any useful sense. Or, they’re only money (whatever you mean by that word) within the Federal Reserve system.”

But surely Federal Reserve Notes are money, whatever you mean by that word. And clearly, reserves may be withdrawn as Federal Reserve Notes at any time. So reserves must be money in a very basic sense, and not only within the Federal Reserve system.

So then the Fed IS “printing money”, and even the title of your post is wrong. I can’t get past this, so I can’t read the whole post, so no doubt I miss your point.

No acknowledgement in the post that reserves are part of base money. “Reserves can’t leave the system, whether in a flood or a trickle.” But of course they can. Reserves stop being reserves when converted into other forms of base money by being withdrawn. So I have trouble with the post.

Analogy:

Reserves are like the money in my savings account. I can withdraw that money at any time and spend it, or just have it. Now I am the first to argue that money in savings does not cause inflation… Money has to be spent to create demand pressures.

But what you are saying is that I cannot reduce the money in my savings account [by withdrawal or any other means]. Clearly that is wrong. And you seem to deny that when the money comes out of my savings account, I am likely to spend it.

Perhaps I am agreeing with Ramanan here.

@JKH

hope you recognized that I use the word “you” in the very general sense in my last two comments – not in the sense of SR

@Asymptosis

“I should have emphasized the words “if anything†in …”

I wouldn’t suggest that either. The clearing system operates on both sides of bank balance sheets. There can be turbulence in the distribution of deposits due to deposit-only activity (i.e. pure payment activity) just as much as in the case of loans-create-deposits activity – and arguably more so.

@The Arthurian

Yeah the Fed prints money whether or not there is QE. It prints currency notes to satisfy banks’ needs to satisfy their customers’ needs for currency notes.

Also, the claim “Fed is not printing money” is as if it is possible for the Fed to do things and create huge inflation and things such as that. Of course it is also erroneous to claim that the central bank cannot create any inflation because it can depreciate the currency and import inflation. Have seen some strange claims (Mosler?) that the central bank cannot create any inflation etc which is incorrect.

@JKH

“distinguishing between a bank reserve balance at the Fed and a bank deposit liability

as forms of money”Did we lose anything there except muddled confusingness?

@Asymptosis

its a specific distinction within the general context of a common sense meaning of money

they’re both forms of money

used to pay for things in their respective realms

(interbank payments versus non-bank payments)

what’s so muddled about that?

IMO, beats an approach that aims at some torturously constructed specific definition of money that is supposed to be unambiguously applicable

if you want to avoid using the term ‘money’, then avoid it, no problem IMO

but if you want to use it, then this is way I would use it

@Ramanan

“My point was you said “Reserves are not “money†in any useful sense.†which is not true actually.”

In what sense is it useful to talk about them as “money” when we can just call them reserves?

The only measure of “money” that includes reserves is the Monetary Base. If they’re not included in any other measure of money, can we call them money? Is it useful to do so?

And dig this definition in wikipedia:

“MB: is referred to as the monetary base or total currency.[8] This is the base from which other forms of money (like checking deposits, listed below) are created and is traditionally the most liquid measure of the money supply.[12]”

So now reserves are currency? Is that a useful way to think about reserves, or currency?

Is the Monetary Base measure “useful” beyond promulgating statements like the following (again from Wikipedia)?

“The monetary base is called high-powered because an increase in the monetary base (M0) will typically result in a much larger increase in the supply of demand deposits through banks’ loan-making activities (an effect often referred to as the money multiplier.)”

The footnote on that?

^ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2002), “Chapter 18: Money Supply and Money Demand”, Macroeconomics (5th ed.), Worth, pp. 482–489

Cavalier, ill-conceived usage of the word “money” (including the inclusion of reserves in the definition of “monetary base” and in statements about the Fed “printing money”) just promulgates this kind of absolute nonsense.

I use wikipedia here just to demonstrate the generally (or at least very widely) accepted understandings and beliefs.

@JKH Money is something that is “used to pay for things.”

I can see that, but it defines the word in a way that’s largely useless in technical discussions. (Think: Nick Rowe-speak, in which we “buy” dollars with our labor, meaning that labor is money.)

I really don’t understand why you push back on this. You’re more careful with your language than just about anyone. You don’t use “money” vaguely or ambiguously. In fact I think you hardly ever use the word at all (because being undefined, it’s not useful).

I’m just saying other discussants (and thinkers) should do likewise. Eschew usage of that word as a term of art.

@JKH

And since when are you resorting to arguments about “common sense” usage!!!? I’m shattered.

Oh, and I realize Wikipedia has a far superior usage for my “reserves” (which is confusing because a bank’s reserves needn’t be held as “reserves” in their Fed account).

Instead:

“Federal Reserve Bank credit”

Or call them Fed deposits.

@Asymptosis

reserve balances at the Fed also works

versus holdings of banknotes that also count toward reserves

common sense is cited only in desperation – but it is all around us in an unspoken way – particularly in double entry bookkeeping

🙂

@Asymptosis

Wikipedia’s errors cannot be used to justify the claim that reserves cannot be called money 🙂

It is a bit counterproductive to change definitions to educate people.

“In what sense is it useful to talk about them as “money†when we can just call them reserves?”

By that logic there is nothing called money – deposits should just be called deposits, currency notes should be called currency notes and so on

@JKH

P.S.

Fullwiler is pretty precise on all this stuff, and he uses the term “reserve balances” consistently

@The Arthurian “surely Federal Reserve Notes are money, whatever you mean by that word. And clearly, reserves may be withdrawn as Federal Reserve Notes”

I can withdraw currency (notes) from my bank. Does that mean that my checking account contains currency? That checking deposits are currency? Careful language matters.

As I said above, yes: this is the other thing that the Fed will issue and retire in exchange for Fed reserves/credit/deposits. And the banking system actually controls this because the Fed is required to make that exchange, issuing/retiring whatever currency banks ask for or send back.

I really should have footnoted this point rather than relying on that link I provided above. Footnoted, because it’s pretty much a non-issue unless IOR is significantly negative. The Fed issues and retires currency as needed (requested by the banks) for everyday transactions. As long as ATMs work and people can deposit cash in the bank, feh. The banks will keep enough cash around to handle that. End of story.

People and banks won’t hold more or less currency because the banks have higher (or lower) Fed reserve balances. There’s no causal there there.

@Ramanan “By that logic there is nothing called money – deposits should just be called deposits, currency notes should be called currency notes and so on”

YES!!! Exactly my point. Since “money” is so vaguely and variously defined (or just, undefined), people (especially economists) shouldn’t use it as a term of art. Like talking about the Fed “printing money.” Or, “demand for money.” Sloppy nonsense.

Here’s an exact equivalent: a discussion of the word “effort” @ physicsforums. A “Mentor” poster says, wisely:

“Whoever wrote that book should be shot! “Effort” is a loosely defined biological/physiological concept that is not directly equivalent to work.”

Now I don’t want to suggest that Greg Mankiw should be shot…

@JKH “Wikipedia’s errors cannot be used to justify the claim that reserves cannot be called money ”

How about Mankiw’s errors?

“Fullwiler is pretty precise on all this stuff, and he uses the term “reserve balances†consistently”

That’s good.

I’m just sayin’: most of the world (cf Mankiw) is not as careful about what they’re saying as Scott, Randall Wray, JKH, and Ramanan. (Ramanan, how often do you resort to talking about “money”? Not often I think.)

That sloppy usage doesn’t just confuse. It creates and promulgates particular misunderstandings (i.e. money multiplier, monetarism in general) that are pernicious.

It strikes that this careful crowd, more than any other, should be supporting (my feeble) efforts to eradicate that obfuscation and…dare I say it?…deceit.

I’ll once again bruit my preferred definitions, which are pretty darned simple, even “commonsense”:

Money: Exchange value as embodied in financial assets

Financial assets: Things that have exchange value but cannot be consumed

These definitions result in us mostly talking about (different types of) financial assets — IMO, a salutary result.

@Asymptosis

I would say “exactly” to JKH’s point. If you want to avoid the usage, then no issues. In fact even I avoid the usage of the word “money”.

But it doesn’t make sense to claim that bank reserves are not money.

@Asymptosis

An analogy: We use terms such as American, European etc. But there is ambiguity. Now a person born as a US citizen may have lived all his life in Bhutan. Or a person not originally from the US – such as born to a couple who are US citizens but originally from Pakistan. And so on. So “American” is ambiguous.

But you cannot use these examples to say “Ben Bernanke is not American”.

@Ramanan “But it doesn’t make sense to claim that bank reserves are not money.”

None of the measures of money M0-MZM include bank reserves. (Only MB does.)

Does it “make sense” that Fed reserves are not money under under any of those definitions?

I would say, “yes.”

Oops, above “bank reserves” should read “reserve balances” or “Federal reserve bank credit,” blah.

“We’re going to define ‘the monetary base’ as including Fed reserves.

“Increases in Fed reserves increase the monetary base.”

Proof positive! Reserves are money!

@Asymptosis

“None of the measures of money M0-MZM include bank reserves. (Only MB does.)”

But MB does.

So “money” = “base money”. Fine.

But MB doesn’t include demand deposits.

So you’re saying that demand deposits aren’t money.

@Asymptosis

“So “money†= “base moneyâ€. Fine.”

Didn’t say equal to.

It strikes me that “base money,” for whatever economic or institutional reasons, has come to be useless and nonsensical as a measure of “money.” The monetarists do love to cling to it, though, living as they do thirty years in the past with no understanding of modern monetary operations or theory. Should we be be participating with them in that blindness?

@Asymptosis

“Should we be be participating with them in that blindness?”

There is no blindness on my part because I know the causality is not from money to price.

I don’t know what the graphs you posted mean – as in what did you want to convey?

$800 billion in currency, $2.2 trillion in central bank reserves, $6.2 trillion in demand deposits. What is the “money supply” (a phrase I’d rather not use)?

@Ramanan

“When banks make loans the money supply rises”

What part of the “money supply” and how?

“When the Fed issues and retires bonds and reserves, it’s not “printing money,†so it’s not playing some kind of simplistic MV=PY game.”

What is the M here?

@Fed Up

Monetary aggregates such as M1, M2 etc are very country specific. In the US, M1 should rise when banks make loans.

How? Simple loans make deposits.

@Fed Up

To be more precise, the Fed is not “retiring” any bond. The bond exists as a CUSIP and is still in existence and has not “retired” in any sense because the Fed may always sell the bonds for some reason.

What about MV=PY?

@Ramanan

So the demand deposit part of the “money supply” goes up. With no extra demand for currency and a 0% reserve requirement, I believe I can come up with a scenario where demand deposits go up but currency and central bank reserves do not.

That leads me to believe that the “money supply” = MOA = MOE = currency plus demand deposits not “money supply” = MOA = currency plus central bank reserves.

@Ramanan

“How? Simple loans make deposits.”

Loans make new demand deposits, not recycle old ones. Right?

@Fed Up

Right with zero reserve requirement, banks as a whole do not need more reserves if they make loans.

@Fed Up

“Loans make new demand deposits, not recycle old ones. Right?”

Yeah.

@Ramanan

It seems to me the fed is taking the bond out of circulation, not retiring it.

“What about MV=PY?”

I don’t think central bank reserves should be included in M. They have zero velocity in the real economy. Assume fed funds rate = zero or near zero. If the fed buys a bond from a bank and the bank does not replace it, then not much happens in the real economy.

@Asymptosis

“It strikes me that “base money,†for whatever economic or institutional reasons, has come to be useless and nonsensical as a measure of “money.†The monetarists do love to cling to it, though, living as they do thirty years in the past with no understanding of modern monetary operations or theory. Should we be be participating with them in that blindness?”

I actually agree with that, but only in the following very specific sense:

It is atrocious to speak of “base money” without automatically differentiating reserves and currency (banknotes) in doing so. That’s where the monetarists are blind and have been absolutely blind in interpreting the financial crisis. It is critical to differentiate the components, because their behavior and functional context is so different.

That said, each component of “base money” is its own form of money, in the sense I described previously, IMO.

So, it is criminally misleading IMO to speak of “base money” without automatically differentiating the behavior of its components, and failing that, one should not speak of “base money” at all.

The category of “base money” is only useful as a consolidation measure of two different forms of money issued by the central bank. It’s still useful to know that information as it is useful always to understand balance sheets.

And I think I might prefer that it be called something other than “base money” – due to the absolutely misleading connotation of money multiplier behavior.

Although I’m not quite sure about that either – there may be a better rationale for retaining the “base” term – as a “basic” or rudimentary form of money, but certainly not as a “base” for the propagation of other forms of money as is falsely purported in monetarist money multiplier land.

@Asymptosis

“Money supply†includes reserves. Definition.”

I believe that depends on the definition. I don’t believe it should. I don’t see central bank reserves as UOA, MOA, or MOE.

@Fed Up

Let’s assume some people get their wish and IOR goes negative, currency still exists, and every entity converts to currency. How much currency will there be?

A) $3.0 trillion

B) $7.0 trillion

C) $9.2 trillion

@The Arthurian

“But surely Federal Reserve Notes are money, whatever you mean by that word. And clearly, reserves may be withdrawn as Federal Reserve Notes at any time. So reserves must be money in a very basic sense, and not only within the Federal Reserve system.

So then the Fed IS “printing moneyâ€, and even the title of your post is wrong. I can’t get past this, so I can’t read the whole post, so no doubt I miss your point.

No acknowledgement in the post that reserves are part of base money. “Reserves can’t leave the system, whether in a flood or a trickle.†But of course they can. Reserves stop being reserves when converted into other forms of base money by being withdrawn. So I have trouble with the post.”

If they (the central bank reserves) were actually “money” in the real economy, then they would not need to be converted into currency.

I see currency and demand deposits circulating in the real economy. I don’t see central bank reserves circulating directly in the real economy.

@Fed Up

MV=PY is an oversimplified equation.

Something like that appears in a stock-flow consistent model but of course the causality is completely different than Monetarism.

At any rate, MV=PY is one thing and definition of money is another.

[…] I’d like to reply to one confusion and one set of pushbacks on yesterday’s post: […]

[…] I’d like to reply to one confusion and one set of pushbacks on yesterday’s post: […]

@JKH

“one should not speak of “base money†at all.”

I’d say we’re agreeing 100%, and for exactly the same reasons.

To avoid the problems you explain so clearly in this comment, why not just talk about reserves and currency, and if you want to talk about both at once for some reason, say “reserves plus currency”?

@Fed Up “It seems to me the fed is taking the bond out of circulation, not retiring it.”

@Ramanan “the Fed is not “retiring†any bond. The bond exists as a CUSIP and is still in existence and has not “retired†in any sense”

I disagree with “in any sense.”

In terms of net net net flows of government (including GSE) bonds into and out of the private sector (issuances minus “retirements”), Fed-purchased bonds are effectively retired. As I emphasized: for the time being.

When we’re thinking about stocks and future flows, the key point: what does “the time being” mean?

Are those bonds permanently retired? Will the Fed hold them forever until they expire? In this brave new world of monetary-policy-via-Fed-balance-sheet-management, I don’t think anybody knows. See the BIS paper I linked to, re: schemes 1 and 2.

I don’t think we learn anything by discussing whether or not the CUSIPs still exist.

And: if the Fed is going to hold them forever, it might as well just burn them. They’re effectively dead and gone.

I hope we don’t need to discuss whether the Fed can actually “burn” bonds, or whether bonds can “die.”

@Asymptosis

The Fed sometimes sell some CUSIPs to buy other CUSIPs for technical reasons.

I think this is misleading. Because, reserves are used when banks create credit. The more reserves a bank has, the more credit they can create in the marketplace.

When person A gets a loan from Bank A and then deposits it in Bank B, Bank A must pony up the money to Bank B at the end of the day. The reserves are what are relied upon to make sure that this can happen. Banks knowing that they have almost unlimited reserves means that once again they are starting to make sub prime credit available, all secure in the knowledge that they can shift as many loans as they want, and they will always be covered.

So technically the Fed isn’t creating dollars, but in reality its the facilitator for banks to be awash with dollars.

@Harvey “reserves are used when banks create credit. The more reserves a bank has, the more credit they can create in the marketplace.”

This is a widespread misconception, not surprisingly because it’s been in the textbooks, incorrectly, for decades. It just ain’t so.

Search for “banks reserve constrained” and you’ll find endless support for this, including ream of papers from central banks worldwide. Here’s a good one to start with.

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2012/07/03/1067591/the-base-money-confusion/

See also the BIS paper linked above.

Also search for “modern monetary theory”. I think you’ll find it as eye-opening as most people have.

@Harvey

Search for “banks reserve constrained†and you’ll find endless support for this, including ream of papers from central banks worldwide.

Yeah they don’t know how their own system works. Amazing. The fact is that as lender of last resort, the Fed always stand ready to provide reserves to clear. There is never a shortage of reserves under a cb that acts as LLR. The question is never over availability of reserves but the cost of obtaining reserves to the bank, since that affects the spread the bank charges. People at the cb may not get this but bankers do.

@Tom Hickey

“Yeah they don’t know how their own system works”

I was referring to the still uncorrected explanations at the central bank sites including the Fed, as well as in places like Wikipedia that quote this.

The papers to which Steve refers are published through the central banks but not officially. They are independent opinion that may not reflect the institutional position. As far as I can tell, the official line has not changed from the money multiplier.

@The Arthurian

@Ramanan

Just to be precise, the Fed never prints notes. The Treasury prints all US currency.

@Jim “Just to be precise, the Fed never prints notes. The Treasury prints all US currency.”

Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that notes are printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which — like the Fed — operates under the aegis of Treasury?

Saying that Treasury prints notes is like saying that Treasury manages monetary policy.