Richard Williamson asks a sensible and straightforward question: If, as Modern Monetary Theorists propose, banks’ reserve levels put no significant constraints on their lending, why don’t we have 100%-reserve banking — and presumably no runs on banks as a result?

First an explanation — I hope simple, clear, and generally accurate (if simplified):

Say you start your own bank. You take in $100 in checking-account deposits and lend it all out, holding no reserves. That’s not safe or even workable. You need some buffer so your depositor’s checks will clear.

So there’s a rule: you can only lend $90, and you leave $10 sitting in your “reserve account” at the Fed — essentially your bank’s checking account. When everybody’s checks clear each night through the Fed’s system, reserves get transferred between banks, and you’ve got enough on deposit so nothing bounces.

If the Fed says you need to hold 12% reserves instead of 10%, that means you can lend $88 instead of $90 — not exactly the massive asphyxiation of the “money multiplier” that many people imagine.

That multiplier is actually related not to your reserves, but to your bank’s capital — the money that you and others have invested (Update: plus profits that haven’t been distributed to owners). That capital is your bank’s buffer against losses from making bad loans. It’s your “skin in the game.”

The amount of capital limits how much you can lend (irrespective of 90%-lent deposits). If the allowed capital-to-loans ratio is 10%, you can lend $10 for every dollar in capital. Now that’s a money multiplier.

The reserve ratio and the capital ratio are completely different things.

So back to Richard’s question: if the Fed required 100% reserves, the banks couldn’t lend out all those checking-account deposits. The quantity of “loanable funds” would decline. But banks could still lend, 10-to-1 (or so), against their capital.

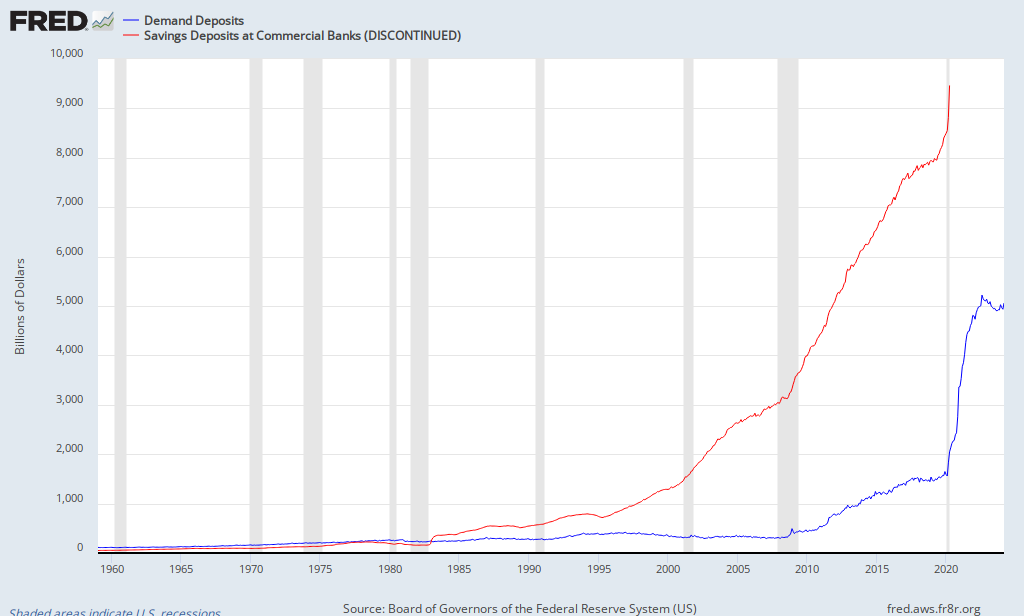

What do those numbers look like in practice? U.S. checking and savings deposits total about $6 trillion right now.

Circa 90% of that would be removed from the loanable funds market. Call it $5 trillion — sounds like a lot.

But total credit market debt outstanding is about $55 trillion.

That makes $5 trillion sound…not insignificant (and profound at the margin), but less onerous.

Which raises my question, one that I’m not knowledgeable enough to answer: Would 100%-reserve banking result in there being more bank capital available — more equity investments in banks — which via its money-multiplying power would offset or more than offset the otherwise decline in loanable funds?

Would we end up with roughly the same amount of credit market debt outstanding?

The answer, it seems to me, would depend on a whole lot of complex and interacting incentive effects. Anyone care to take a stab?

P.S. Like me, you’ve no doubt noticed that debt outstanding is in fact about ten times bank deposits. Does this put the big-picture lie to the MMTers’ claim that lending is not reserve-constrained? Is it just a coincidence? Other?

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

5 responses to “Full-Reserve Banking and Loanable Funds”

[…] Cross-posted at Asymptosis. […]

[…] Cross-posted at Asymptosis. […]

don’t lend out reserves or against reserves. Bank reserves are for interbank settlement of accounts, which happens in the FRS (on the Fed’s spreadsheet). As the lender of last resort the Fed always makes sufficient reserves available to solvent member institutions for settlement of accounts. Banks without excess reserves at the Fed obtain needed reserves in the interbank market at the rate the Fed sets (FFR). There is also the discount window; if a bank comes up short in a period, the Fed supplies the reserves and charges the penalty rate.

Banks lend against capital, that is, they put capital at risk in lending. Loans create deposits. Banks arrange for reserves for settlement after lending, not before lending. Reserves do not constrain lending. Capital requirements, risk, and demand for loans are the operative constraints.

The cost of obtaining reserves, i.e., the overnight rate, determines in part the cost of lending. Increasing the reserve requirement also increases the cost to the bank of making the loan. This cost is figured into the lending rate that the bank offers to its customers based on risk assessment.

There is neither a money multiplier nor a stock of loanable funds. These are concepts that apply to a convertible fixed rate system where the central bank has to manage base money relative to the reserve for convertibility, e.g., stock of gold. The US has been running a nonconvertible floating rate system since President Nixon closed the gold window on August 15, 1971. The world officially adopted the nonconvertible floating rate system in 1973.

@Tom Hickey

See, for example, Scott T. Fullwiler, “Modern Central Bank Operations– The General Principles” (June 2008).

Can’t answer your 1st question, but in regards to the 2nd: No, it doesn’t. It just means that the reserves follow the loans. The ratio doesn’t change, just the causality.