Some years ago Paul Krugman gave perhaps the best argument against the inequality-causes-underconsumption theory of secular stagnation: the idea that rich people spend less of their income/wealth, so if wealth/income is more concentrated there’s less spending and less GDP/prosperity.

(It’s curious how liberal economists are the ones who most commonly shoot down this argument. That’s the subject of my next post.)

There are two parts to Krugman’s argument: theoretical and empirical. I find both to be weak or fatally flawed. Theory first:

at any given point in time the rich have much higher savings rates than the poor. Since Milton Friedman, however, we’ve know that this fact is to an important degree a sort of statistical illusion. Consumer spending tends to reflect expected income over an extended period. If you take a sample of people with high incomes, you will disproportionally include people who are having an especially good year, and will therefore be saving a lot; correspondingly, a sample of people with low incomes will include many having a particularly bad year, and hence living off savings. So the cross-sectional evidence on saving doesn’t tell you that a sustained higher concentration of incomes at the top will lead to higher savings; it really tells you nothing at all about what will happen.

Parsing this:

1. This argument just says that we don’t know, using this theoretical construct, whether the underconsumption argument is valid. It doesn’t disprove it, rather it just fails to support it. Other quite cogent theoretical constructs do support it. For some reason even liberal economists don’t turn to these constructs.

2. That construct requires fairly strong belief in a fairly strong form of Friedman’s “lifetime income hypothesis,” a hypothesis that has been cogently challenged on many grounds. Since this weakens the value of the theoretical construct, it weakens the “we don’t know” assertion that arises from that construct. We might actually have a pretty good idea, looked at certain ways.

3. Further weakening: It relies on saving as an indirect measure of people’s spending (consumption spending is what we’re asking about here), rather than looking at spending directly. And it doesn’t consider people’s spending relative to their wealth — arguably a much more revealing measure if we’re considering “rich people’s spending.” The saving/spending nexus in national accounting is a very sticky wicket, combining changes in income, borrowing, lending, home values, imputed rent, and capital gains in often unintuitive and confusing ways. If we’re asking a question about spending, it’s usually best to look at spending directly, and that relative to wealth, not income (due to the very statistical problems that Krugman highlights).

In any case, Krugman throws his theoretical hands up, and resorts to empirics:

So you turn to the data. We all know that personal saving dropped as inequality rose; but maybe the rich were in effect having corporations save on their behalf. So look at overall private saving as a share of GDP:

The trend before the crisis was down, not up — and that surge with the crisis clearly wasn’t driven by a surge in inequality.

I find all sorts of problems with this:

1. This graph looks at gross private saving, which includes the financial sector. As Krugman has himself made clear, “saving” by the financial sector is a qualitatively different animal from real-sector saving. It’s huge, it changes a lot over time, and those changes are impossible to parse out by eye looking at this graph.

2. Even if you look at real-sector only (households and nonfinancial businesses), “saving” is heavily influenced by lending/borrowing/payoff trends. It’s a complicated measure to use to discern spending as a percent of assets or net worth or wealth.

Just to emphasize how problematic “saving” is as a measure to evaluate this spending question, consider how important “imputed income” is in the BEA measure of Personal Saving. By far the biggest portion comes from imputed rent, which is itself closely tied to property values hence unrealized capital gains (from heavily leveraged investments), at least in the medium to long run. This even though capital gains are not, according to most national accounting usage, “income.”

You would think that this measure would be straightforward (Income minus Expenditures), but it decidedly isn’t. Take a look:

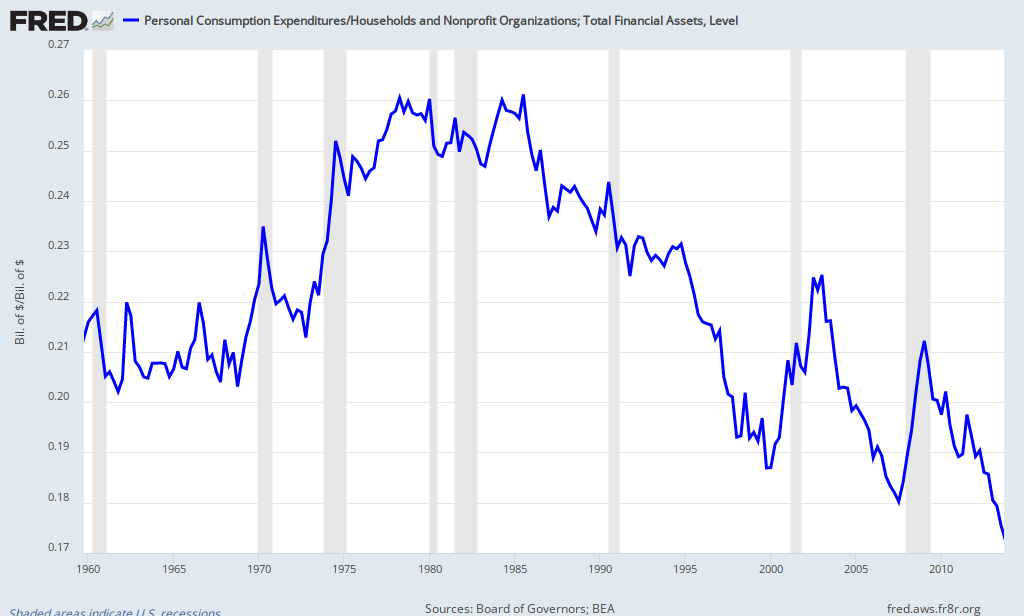

Yesterday I posted this graph as potentially giving us better insight into the question at hand — Personal Consumption Expenditures as a percent of Household Financial Assets:

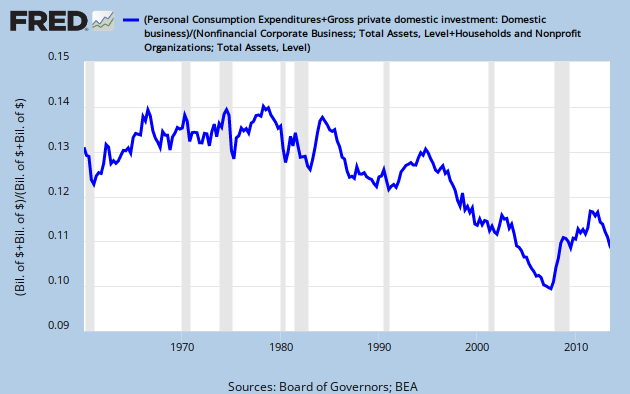

I’ll add another here:

(Personal Consumption Expenditures + Business Investment Spending) / (Household Total Assets + Business Total Assets)

Update: This is all nonfinancial business.

It’s a remarkably similar picture — at least regarding the long-term trend since the 80s.

So there’s some empirics giving some support for what Krugman calls the underconsumption story. (Bad name for it, in my opinion.)

Now how about some of our leading liberal economists delivering on the theory?

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

6 responses to ““Saving” and Underconsumption”

Nice! Krugman’s post stuck in my craw, too, but I couldn’t cough up a satisfactory response.

I like your last two graphs, comparing current spending to accumulated savings.

I completely agree. Steve R Waldman also gave this link:

Why Do the Rich Save So Much? Christopher D. Carroll

http://www.econ2.jhu.edu/people/ccarroll/Why.pdf

It points out that Bill Gates at that time would have needed to spend about $10M per day simply to have avoided accumulating more. How is anyone supposed to achieve such a level of consumption?

[…] Yesterday I took on the strongest argument I’ve found* against what Paul Krugman calls the “underconsumption” story (not a good moniker, IMO), an argument from…Paul Krugman. I found it to be seriously unconvincing. You can draw your own conclusions. […]

Incidentally, I thought Steve Randy Waldmann gave the best counter to Krugman’s argument when it came out, but I have not seen Paul Krugman or any similarly minded economist respond to his points:

http://www.interfluidity.com/v2/3830.html

For my own short takedown: The empirical argument falls apart because it depends on the Permanent Income Hypothesis, which isn’t well supported by the evidence.

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/09/business/09scene.html

And the empirical argument falls apart because, while it suggests that rising income inequality can be compatible with steady consumption, what it would need to suggest to be convincing to me is that rising consumption inequality can be compatible with steady consumption. But that empirical case isn’t made, because consumption inequality didn’t rise much. The Gini coefficient of the consumption distribution is lower than for the income distribution, and has risen more slowly:

http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2005/04/art2full.pdf

So the sustained high consumption pre-crisis needs no explanation; in spite of stagnant wages the middle class kept up their share of consumption as the economy grow. Now that the middle class has hit a wall of debt and can’t take on any more in spite of ever lower rates, that has changed, and the rich have not stepped in to replace to replace the consumption that the middle class was financing with debt. Indeed they have no more reason to consume now than they did pre-crisis.

[…] theoretical argument against what Paul calls the “underconsumption” theory than my feeble effort (though do look at the graphs in that […]

@Eric L:

All great stuff.

And hell, just ask producers/entrepreneurs: would you rather have ten million people who can afford your product, or a hundred million? Unit sales matter.