Update: More expansive discussion of this model with more graphics, here.

Update 2: There is a revised and corrected version of the model and spreadsheet here, with discussion.

It has long seemed to me that redistribution is, for some reason, necessary for the emergence, continuance, and growth of large, prosperous, modern, high-productivity monetary economies. No such economy has ever emerged absent large quantities of ongoing redistribution. There are no exceptions; every such economy on earth engages in it on a large scale. The Economist recently devoted a whole special section to the need for Asian countries — notably China — to develop such systems of social redistribution in order to make the move from “developing” to “advanced.”

That’s the big-picture empirics. What I’ve been missing, have been unable to find, and have been struggling to conceive, is a straightforward, intuitively convincing economic model (mathematical or at least arithmetic) to explain this fact theoretically.

Paul Krugman says that thinking in terms of models will make you a better person. I want to be a better person.

I think I may have finally created such a model. (I’m feeling better already.) It’s a very simple dynamic simulation model (set it up, plug in parameters, and watch it run over the years), and it’s purely monetary. It makes no attempt to model the real economy of production and trade in real goods. It makes no distinction between consumption and investment spending; there’s just spending. It doesn’t require a theory of value, or of capital, or of profits. It simply assumes that production and trade happen, and that they yield a surplus. You can imagine that surplus as consisting of new real assets, or being embodied in new financial assets that are representative of those real assets. It doesn’t really matter.

The model is based on one and only one behavioral assumption: declining marginal propensity to spend out of wealth. (Something I fiddled with previously, here.) That in turn is based on the declining marginal utility of consumption (the millionth dollar spent yields less utility than the first). The assumption, which seems safe both empirically and theoretically:

Rich people spend a smaller portion of their wealth each year than poorer people.

In this model each person’s spending is replaced each year by income (with a surplus), but the spending is determined by the person’s wealth. It assumes that people expect the income to replace the spent wealth, but they’re not certain that it will, always. So they (especially those with low income/wealth) are facing a tradeoff between present spending and long-term economic security. Different wealth/income levels have different propensities to substitute one for the other.

This is basically looking at spending and income from the opposite direction of most such models. Here, spending drives aggregate income (all spending is income, when received), rather than spending being determined by income (which is how we tend to think about individuals).

The rest is just arithmetic.

Here’s the basic setup, with a population of 11 people. The spreadsheet is here (Google Doc version here); you can change of the numbers and see the results.

I’m assuming 0% inflation for simplicity.

One person has $1 million.

Ten people have $100K each: $1 million total.

The rich person spends 30% of their wealth annually ($300K to start).

The ten poorer people spend 80% of their wealth annually ($80K each, $800K total, to start).

Through work/production and gains from trade, each person gets 5% more income annually than they spend. I’ve black-boxed that whole surplus-creation process; it just happens. I’ve set it up so that income (including the surplus) is distributed to the population proportionally based on how much they spend. It’s a somewhat arbitrary choice (I had to make some choice), but since people’s incomes and expenditures do tend to correlate fairly closely, it doesn’t seem like a nutty one.

The additional money for this annual +5% would come from new bank lending and/or government deficit spending and/or Fed money printing and/or trade surpluses with other countries. Choose your monetary model/paradigm; in any case the surplus is monetized via trade and the financial system.

So no, Income ≠Expenditure (or vice versa), unless you include purchases of new financial assets in “Expenditures.” Absent those purchases/receipts, Income is 5% greater than Expenditures. That’s what surplus from production/trade is all about, how it plays out in an economy that includes monetary savings.

Now add this: Some percentage of the rich person’s wealth is transferred to the poorer people every year (by the ebil gubmint man).

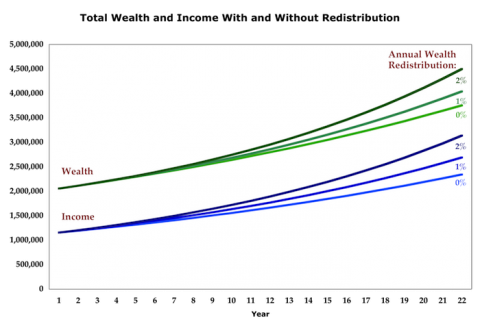

Does that wealth transfer make everyone wealthier, or poorer? Here’s the result with the numbers I set out above:

In this model, taking money from the rich and giving it to the poor make us more prosperous in aggregate, raises all boats, makes the pie bigger…you’ve heard all the metaphors.

The arithmetic, and the theory, is simple:

1. Redistribution results in more spending (because of declining marginal propensity to spend from wealth)

2. More spending spurs more production

3. More production (and trade) produces more surplus

4. Surplus (monetized) is the source of monetary savings

5. Bonus: More savings (wealth) results in more spending. (Note the exponential curves.)

6. Repeat loop.

The result seems to be an apparently counterintuitive, but on consideration very obvious, conclusion:

Saving doesn’t cause saving. Spending causes saving.

The preceding is halfway tongue in cheek. It points out how problematic the word “saving” is in a monetary context. Saving some of this year’s corn crop is straightforward enough — eat less of it. Money makes it into a far more complicated concept, cause you can’t eat money.

I would say instead:

Spending causes accumulation, because it spurs production and trade, resulting in a surplus. That surplus is what allows for accumulation.

So we want more spending, and less so-called “saving.” Some people call it money hoarding, but that’s confusing too. The best synonym for monetary saving is “not spending.”

I’m with Nick: we should stop using the word saving.

More monetary saving by individuals (the word works fine for individuals) — spending a smaller proportion of their wealth on real goods each year — results in less accumulation in aggregate.

Faithful readers will recognize that this purely monetary model sidesteps and obviates the need for the conceptual quagmire associated with S = I = Y – C — a construct which, in its effort to go in the opposite direction from mine and model a barter, real economy devoid of monetary savings, arguably makes it impossible or at least very difficult to think cogently about how monetary economies (i.e. all economies) work.

But how about sharesies? Is it fair? Here’s how it plays out:

| 20 Year Change in Income/Wealth | |||

| Redistribution | Rich Person |

Poorer People | All |

| 0% | 35% | 119% | 96% |

| 1 | 10 | 165 | 123 |

| 1.5 | 0 | 192 | 139 |

| 2 | -10 | 221 | 158 |

At 1.5% redistribution in this model, the rich person’s income, spending, and wealth all stay the same over time (remember: no inflation here), while the poorer people’s income and wealth almost triple, and overall wealth and income more than doubles. Seem fair to you? Pareto devotees please comment.

I know exactly where everyone’s going with this: incentives and behavioral responses. And I have to admit that I did make one other behavioral assumption here: that there are no other behavioral responses.

Giving a bit less money to the rich person will give slightly less incentive to work. But at the same time it’s giving ten poorer people far more incentive to work. You do the math. (This all before we get into issues of substitution vs. income effects at different wealth and income levels, something I won’t even begin to address here.)

Whatever combination of behavioral effects one might posit, I would suggest that the burden of proof lies with the positor to demonstrate, empirically, that those effects are sufficient to overwhelm (or supplement?) the inexorable arithmetic of compounding that’s at play here.

Finally, note that this model doesn’t even touch on aggregate utility delivered under each regime. Since the spending of the poorer people is split among ten — each spending $80K/year to start — a larger proportion of that spending is on necessities like food, clothing, shelter, health care, and education. I think all economists will stipulate to the proposition that those purchases yield higher utility per dollar than a family’s purchase of a third car or a fourth TV. So the graph above greatly understates the higher aggregate utility provided by redistribution, and the table either understates the utility gains by the poorer people, or overstates the gains by the rich one. (It would be easy to add a somewhat arbitrary formula to represent that effect graphically, but I’ll leave it to your imagination.)

And: this utility effect would serve to multiply the incentive for poorer people discussed in the previous paragraph, giving the ten people even more incentive to work.

I’m rather taken with this spending + surplus = income dynamic approach to modeling. (But I would be, wouldn’t I?) I’d be delighted to see how others might analyze and display results using various parameters, and how they might adjust, improve, or dismantle the model. In particular: are there obvious, gaping flaws here?

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

57 responses to “Modeling the Wealth, Income, and “Saving” Effects of Redistribution: More is Better?”

Steve “Kaldor” Roth?

The concept of ‘redistribution’ is theory-laden. It is part of loanable funds theory. In MMT, it is not a redistribution at all: it is about destroying the money (by taxing) of one segment, and creating money (by spending) for another segment.

@Ramanan: “Kaldor”

Very interesting! Perused wiki and saw some similarities, but not terribly close. Can you point me to any Aha items?

@Pedro: As I said over at AB, I understand the rhetorical and political baggage attached to “redistribution.” But in this post that was a non-issue for me. The MMT construct you suggest is effectively the same thing as taking here and giving there. The government, like the production sector (which overlap, btw), is a black box in this model.

Interesting stuff Steve. I guess Robert H. Frank would make the point that since the wealthy person is left in roughly the same economic position relative to the 10 lower income earners his lifestyle doesn’t change because he still has dibs on positional goods like the biggest house or the most expensive car in town.

The trick with Saving is making the distinction between individuals and aggregates. At the Macro level, instead of Saving, call it McSaving. :o)

http://blog.twowholecakes.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/scrooge-mcduck.jpg

Finally, since Ramanan wishes Nicholas Kaldor and Wynne Godley were his two dads (neither was gay so I’m not sure how that would work either), that was high praise indeed. I believe he was referring to Kaldor’s stylized facts.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaldor%27s_facts

Steve,

What causes income & wealth to increase?

@vimothy: “What causes income & wealth to increase?”

Work and production with resulting surplus, and monetization of that surplus through trade and the financial system.

@Asymptosis

Sorry, I’m probably being dense–how are you modelling that? It looks like spending causes wealth and income to increase.

@vimothy “It looks like spending causes wealth and income to increase.”

Zactly. Might want to read through the post again. That’s pretty much the whole point of it. Sort of a conceptual jiu jitsu on the standard understanding.

Thx.

@Asymptosis

So, what I mean is, why? What’s the logic behind that?

@vimothy “It looks like spending causes wealth and income to increase. … What’s the logic behind that?”

Saving doesn’t cause “saving.” (Or, “saving” doesn’t cause saving.)

The logic: individual saving (individuals spending a smaller proportion of their wealth or income each year) doesn’t produce aggregate “saving.” QTC.

If you pay me $100K in wages, there’s no change in aggregate bank balances, just a transfer between bank accounts.

If I buy $100K in goods from you, same thing.

If I save instead — leave $25K in my bank and buy $75K from you — same thing. No change in aggregate “savings.”

Spending is what causes production, trade, surplus, and accumulation — true national “savings.”

Likewise, saving doesn’t cause investment. Spending causes investment.

In fact, investment is spending.

@Asymptosis

“Saving doesn’t cause “saving.†(Or, “saving†doesn’t cause saving.)”

In your model, there is no capital, and hence no need or even really the possibility of saving in a macroeconomic sense. It would be better if the economy spent its “wealth” as fast as possible, since this would raise its income faster.

So, in your model, what you say is true because of the assumptions that you have made.

On the other hand, if you were to model the productive side of the economy, even at its most simple, then you would need to somehow account for either the growth in factor inputs like labour and capital or technological change.

When you do this, saving (meaning *aggregate* or macroeconomic saving) becomes necessary for future income, since capital depreciates and income is a function of capital.

@Asymptosis

Well, investment is a type of expenditure. But it’s not really like spending in the sense of consumption expenditure. If I spend my income, my income is gone. On the other hand, if I use it to purchase assets, then I’ve taken one asset (cash or whatever) and swapped it for another asset. My wealth is (hopefully) unchanged.

The essential point about saving from an economic point of view is that some current resources are kept back for future use. Investment is a use for those resources (on some level, the only use). Spending means that current resources are being used up.

@vimothy “In your model, there is no capital, and hence no need or even really the possibility of saving in a macroeconomic sense. It would be better if the economy spent its “wealth†as fast as possible, since this would raise its income faster.”

I’m assuming you mean real capital — stuff that humans can consume/use to deliver utility.

Since it’s a purely monetary model, yes, real capital is external to the model.

But it’s assumed that new real capital is monetized by the financial system — that the growing stock of financial assets (roughly, long term) correlates to the accumulated stock of real capital.

That process is black-boxed. It just happens. It’s what the financial system does.

“So, in your model, what you say is true because of the assumptions that you have made.”

True. If the assumptions (i.e. financial system monetization of surplus/accumulation/real capital) were different, the conclusion might be impossible. But isn’t that true of any model?

“On the other hand, if you were to model the productive side of the economy, even at its most simple, then you would need to somehow account for either the growth in factor inputs like labour and capital or technological change.”

Right. That’s black-boxed too.

“Well, investment is a type of expenditure. But it’s not really like spending in the sense of consumption expenditure.”

Right. And it’s very important to distinguish conceptually between consumption spending and actual consumption.

http://www.asymptosis.com/eating-the-seed-corn-consumption-in-the-american-economy-since-1929.html

“If I spend my income, my income is gone.”

1. You can’t “spend income.” Meaningless concept, or just a convenient shorthand for spending more or less than your income in a given period. There’s no way to “spend” out of the instantaneous moment that I hand you a five dollar bill. You can only spend out of the $5 that’s in your hand or your pocket.

2. No it’s not gone; it’s in somebody else’s bank account (received as income).

“The essential point about saving from an economic point of view is that some current resources are kept back for future use. Investment is a use for those resources (on some level, the only use). Spending means that current resources are being used up.”

No! Consumption means that real resources are used up. Spending ≠Consumption Spending. That confuses the thing with the accounting method we use to measure the thing within a period (and excludes consumption of fixed capital, which is clearly “consumption”).

You’re confusing spending with consumption.

Spending = Consumption Spending + Investment Spending.

And:

Investment Spending (which by convention is Gross Investment Spending) = Net Investment Spending (increase in the real capital stock) + Consumption of Fixed Capital.

So: my model says nothing about the value of investment spending vs. consumption spending. Again, in this model that’s all in a black box that yields 5% surplus for each dollar spent.

That surplus consists of real, accumulated assets — in keeping with Kuznet’s statement that the true wealth of the nation is that stock.

The increasing “wealth” depicted in this model is a monetary representation (monetized via trade and the financial system) that roughly correlates to the value of that increasing, accumulating stock of real assets.

@Asymptosis

“I’m assuming you mean real capital — stuff that humans can consume/use to deliver utility.”

I mean capital as in stuff that is produced that can be used to produce more, like machines, and so on.

“Since it’s a purely monetary model, yes, real capital is external to the model.”

What do you mean by a “purely monetary model”? If there is nothing but money in your model, what is the point of spending or earning? And who is there to do the spending and earning?

“But it’s assumed that new real capital is monetized by the financial system — that the growing stock of financial assets (roughly, long term) correlates to the accumulated stock of real capital.”

Capital needs to be produced. The only way capital can be produced is if the economy saves, i.e., does not consume but rather invests.

In your model, “spending” drives output. The more spending there is, the more output there is. What you call “spending”, I would call “expenditure”. Since output is a function of capital (among other things), the more investment expenditure, the more output.

Capital is how economies save. So, without saving, no capital is produced. And, over time, output will go to very low levels–though perhaps not to zero.

In other words, what’s important is not that there is a lot of expenditure, but that there is a particular type of it, namely investment, if maximising income is what is important.

At the same time, maximising income is a bit redundant if there is no consumption, so there is a (one of Mankiw’s favourite terms, IIRC) trade off between the production of capital goods and the production of consumption goods.

“True. If the assumptions… were different, the conclusion might be impossible. But isn’t that true of any model?”

Yeah. But you’re more or less assuming your conclusion. There’s nothing wrong with that, necessarily, but it does mean that it makes your argument less persuasive to those of us not already predisposed to it.

“Right. And it’s very important to distinguish conceptually between consumption spending and actual consumption.”

I’m sure that it’s important in some contexts. E.g., a child’s games console could be considered an investment good because it yields a future stream of consumption goods. But it’s not always necessary to model the economy in such great detail that such distinctions matter.

“You can’t “spend income.†Meaningless concept, or just a convenient shorthand for spending more or less than your income in a given period. There’s no way to “spend†out of the instantaneous moment that I hand you a five dollar bill. You can only spend out of the $5 that’s in your hand or your pocket.”

I’m sure I’m missing your point here. If I earn $5, then it doesn’t seem hard to see how I could spend it. If you mean that as soon as I earn the $5, it is added to my wealth and so all spending is spending from wealth, I don’t see why I shouldn’t retain “spend income”. If I were to say “I spent my income”, then the listener would know that I have spent all of my current period income. I don’t think that that is meaningless.

“No! Consumption means that real resources are used up. Spending ≠Consumption Spending. That confuses the thing with the accounting method we use to measure the thing within a period (and excludes consumption of fixed capital, which is clearly “consumptionâ€).”

I don’t worry too much about accounting methods. Accounting is not economics. Accounting is a measurement tool, one of many. When we’re discussing theory, as here, measurement is irrelevant.

“You’re confusing spending with consumption.”

What I’m doing is retaining the word “spending” for consumption expenditure in particular.

When I ask google to define “spent”, it gives me the following:

spent

Adjective

Having been used and unable to be used again: “a spent matchstick”.

Having no power or energy left: “a spent force”.

When income is spent on consumption goods, it is gone, spent, unable to be used again.

When income is “spent” on capital, it is not gone. It is retained, available for future use. It is saved.

If you use the spending to refer to any kind of expenditure whatsoever, then you are asking for confusion, it seems to me. But YMMV.

I don’t know. Maybe there was no need to say all that. I’m sure we could argue all day about what the word “spend” means and never get any where.

Where I was going initially was that there’s no particular reason to think that output is a function of spending or expenditure or whatever, and that saving, for the whole economy, is clearly necessary if income is to grow or even stay at a constant level over time.

Incidentally, although I’ve maybe been a bit critical of your model and I think you strawman mainstream economics, I’ve really enjoyed your recent series of posts about modelling. It’s a topic close to my own heart and I think it gets completely ignored in this part of the blogosphere.

Are you familiar with the Ramsey model (from Ramsey 1928)? It’s usually the first macro model you learn when you study economics. I find that there’s an interesting overlap between it and what you’re doing here. You may see it differently, of course!

I guess you’re already familiar with it, Steve, but if your readers are interested, there’s a (not particularly informative) Wikipedia page:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramsey%E2%80%93Cass%E2%80%93Koopmans_model

And what seems like a better, more extensive treatment in these online notes (I’ve only scanned through them, but they seem reasonable–google has much more):

http://www.econ.ku.dk/okocg/MAT-OEK/Mak%C3%98k2/Mak%C3%98k2-2011/Lectures%20and%20lecture%20notes/Ch10-2011-1.pdf

@vimothy

I really think you’re confuting two things here. (And you’re not alone.)

1. Creation and accumulation of real capital.

2. Monetary “savings” — creation and accumulation of financial assets.

“Income” and “Expenditure” (or “Spending”) are always monetary.

So “saving” income (synonym: not spending) does not create real assets.

And it doesn’t create aggregate monetary “savings.” It only affects which bank accounts the money is held in.

And: In standard usage at least (agreement necessary for us to communicate), Expenditure (“spending,” whatever) does not mean Consumption Expenditure.

Y = E = I + C

Glad you’re finding some value in my posts. It’s painful to have people watch me figuring things out, but it seems to be the only way I can do so.

@vimothy

A condundrum for you:

I produce 1000 bushels of corn.

1. People buy and consume it all.

2. Or: people buy and consume only 500 bushels.

In #2, has “the economy” “saved”? Technically yes (because bought-and-consumed inventory [the definition of Consumption Spending] is deducted from I).

Add time and incentives. In #2, I’ll only produce 500 bushels in year 2.

Which “economy” will “save” more?

@Asymptosis

Steve,

Aggregate expenditure can be decomposed in a variety of ways. Consumption expenditure is a component of aggregate expenditure. I don’t think that I’m using these terms in ways that are unusual. Spending I would say is consumption expenditure. Investment expenditure is not spending. Purchasing financial assets is not spending. You say so yourself, I think: “saving†income (synonym: not spending).

What you seem to be saying here, translated into my language, is that there is no particular link between the micro level saving of the individual and the aggregate saving of the economy. I.e., the old argument that goes back to Keynes at least and probably beyond that.

Whereas what you seem to be concluding from your model (among other things, perhaps) is that aggregate expenditure *of any kind* causes aggregate saving. At least, I think that’s what you’re concluding. It’s certainly false, by the way, because there can be no aggregate saving without capital, so that, if all of the expenditure represents consumption, aggregate saving is zero (in fact negative, with depreciation).

At any rate, the two cases are different. If you want to talk about the relationship between aggregate expenditure, aggregate saving and aggregate income, then I think you need to include production and capital. Otherwise, what’s the point of saving? How is saving even possible?

If on the other hand you want to talk about the link between individual micro level decisions and the aggregate outcome in terms of investment and output then you’re going to need to model the actors involved. That will also require being explicit about production and investment, as far as I can see.

@Asymptosis

In #1, the economy has literally saved. In the final period, (the upper bound of) its consumption will be 1500 bushels of corn.

In #2, the economy has not saved. In the final period, (the upper bound of) its consumption will be 1000 bushels of corn.

1500 > 1000.

I’m not sure how much you can conclude about the behaviour of real economies from this example, though. Why are you focusing on *inventories*?

If economy one consumes all of its output and economy invests some fraction of its output, economy one will have zero (aggregate, gross) saving and economy two will have a positive amount of saving. That’s by virtue of the assumptions we’ve just made and there is no way around it.

Consumption = income -> saving = zero.

@vimothy

I think the point is:

Investment expenditures (by definition) create “national wealth” in the form of enduring (productive) assets. That’s what investment expenditures are, by definition — spending on goods that aren’t consumed within the period (that includes both fixed assets and inventory, btw, though inventory changes are fairly small as a proportion of changes in the stock of enduring assets).

Consumption expenditures (are the only things that?) incentivize investment expenditures.

Again, in my model there’s no differentiation; there are just expenditures. Different investment/consumption mixes would undoubtedly yield different quantities of surplus (short- and long-term).

I just assume that the spending — and the incentivized production that results — yields a 5% surplus (inputs -> outputs), which is monetized via trade and the financial system.

So the increasing stock of real assets (which I think we both agree is the real “savings” or accumulated “wealth” of the nation — its productive capacity) is represented here by the increased stock of financial assets (“money” or “wealth”).

An aside:

The NIPAs only count “Fixed assets” as a measure of the nation’s productive “capital.”

This is broken down into structures, equipment (hardware), and software. Structures is further broken down into residential and non-residential.

Fixed Assets is a subset of real, productive assets. It does not count many real, productive assets that are hard or impossible to measure.

If you take a course to learn computer programming, for instance, you’ve created a real, productive asset — call it knowledge, skills, whatever. It adds to the true wealth of the nation — its productive capacity.

When a company institutes a new set of procedures that makes its employees more productive, that set of procedures is a real asset. In fact I’d argue, based on having run multiple valuable companies that had almost no fixed assets (some computers, a phone system…), that a huge amount of companies’ value (and the national wealth) resides in such intangible and impossible-to-measure “organizational capital.” That is real capital.

And: the stock of financial assets roughly represents that total stock of real capital (fixed/measured and other/unmeasured). When “the market” thinks the economy will be more productive, it bids up the value of those financial assets, representing the increase in “real wealth”/”productive capacity.”

@Asymptosis

Steve,

Right, so my criticism is this: in your model, you assume that income is an increasing function of expenditure, and savings are an increasing function of income. Consequently, savings are increasing in expenditure.

My original question was: why are these reasonable assumptions?

You’ve “black-boxed” production as following an exogenous, predetermined process, but then used your model to draw conclusions about the relationship between expenditure and savings and income. If you want to do that, then you need to make the underlying relationship explicit.

If I were to say, for e.g., my model says that taxes on the very rich lower income for everyone, because I’ve assumed that taxes on the very rich lower income, you might not find my results particularly persuasive. If on the other hand I were to start with a set of assumptions that you can agree with, and then draw my conclusions, you might find it harder to argue with them.

On your aside:

I don’t worry too much about what it says in the NIPA or SNA. If I were doing some applied work, I might, but in general I’m interested in economic theory and not whether a category in the NIPA contains a, b, c, d, e, f and g, or just a, b, c, d, e and f.

With that said, of course you are quite correct that not all capital is fixed assets. In fact, and quite obviously on reflection, the lion’s share of national wealth is intangible and human capital.

I’m not sure that I agree that it’s impossible to measure, but it’s surely very difficult. To my mind this shows both the problems inherent in the overwhelming PKE focus on aggregate statistics like the NIPA, and the relative good sense of mainstream econ, which makes this a major point of focus (at least in macro, but doubtless in micro too, though I know even less about that).

@Asymptosis

And: the stock of financial assets roughly represents that total stock of real capital (fixed/measured and other/unmeasured). When “the market†thinks the economy will be more productive, it bids up the value of those financial assets, representing the increase in “real wealthâ€/â€productive capacity.â€

That’s exactly right and exactly as it should be.

Most of the value of firms comes from intangible and human capital. The future is uncertain and subject to change, so current valuations of future output are also subject to variation.

Dynamic modelling, human capital, stochastic changes in the productive capacity of firms–Steve, you’re not only sounding neoclassical, you’re bordering dangerously close to RBC theory!

@vimothy “you’re bordering dangerously close to RBC theory!”

How dare you!!! 😉

Really, no.

We (necessarily) talk about (many of) the same constructs, but say very different things about them.

Because RBC is in Say’s Law world — that supply creates (causes) demand (by throwing off wages and profits).

My assertion is exactly the opposite — demand creates (causes) supply (and production, and trade, and surplus, and jobs, and profits, and accumulation of real and financial assets, and wealth, and…).

This is way Keynes. I think he said something like “everything comes from demand.”

The two are looking at the same cycle (expenditure = income = expenditure = …), but attributing different causations at different points in the cycle.

These are, finally, behavioral assertions, dontcha think? About incentives. I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that demand is the ultimate incentive spurring supply.

@Asymptosis

Steve,

Let me remind you what you just wrote a couple of comments up:

And: the stock of financial assets roughly represents that total stock of real capital (fixed/measured and other/unmeasured). When “the market†thinks the economy will be more productive, it bids up the value of those financial assets, representing the increase in “real wealthâ€/â€productive capacity.â€

From this (which I agree with), we can see that wealth–the value of future output–is an increasing function of the capital stock, most of which is intangible and/or human.

Now you want me to believe that wealth is a function of… demand? How, if aggregate nominal expenditure increases, does the economy become more productive? Demand is just an arbitrary value. It has importance in the context of a business cycle where firms are expecting a certain level of sales, but it doesn’t make people more productive. It doesn’t teach my how to programme C++. It doesn’t reorganise my start up so that it becomes more efficient. It’s not capital accumulation. It’s not technological change.

If you pull back so that we’re looking at long-run growth, what does demand have to do with it? Nothing whatsoever, as far as I can see. You had it right the first time: wealth = capital stock = for the most part human capital.

If we stop sending children to school, future income will be lower, regardless of the level of demand or nominal expenditure.

@vimothy

Oh, and:

Here’s what I think your basic objection to the model is.

The investment/consumption mix for rich and poor people might be (is) different.

Rich people spend more on investment, poorer people more on consumption.

Redistribution’s effect — increasing total expenditure due to marginal propensity to spend — might be overwhelmed by the resultant proportional decline in investment spending relative to consumption spending.

IOW, the effect of increased aggregate expenditures due to redistribution (with a greater percentage increase in consumption expenditures, which incentivizes but does not contribute directly to investment in an accounting sense) — might not make up for the reduced proportion of investment spending in the mix.

But I don’t think that arithmetic makes sense.

Or actually I think the logic doesn’t make sense.

Increased capacity doesn’t create (cause, incentivize) increased demand.

Increased demand (spending, expenditure) *does* cause, incentivize the creation of additional capacity.

You could say: investment spending generates wages because the additional capacity has to be produced.

But that effect is exactly the same with consumption spending. It generates wages because the additional quantity has to be produced.

So that’s a wash. It’s all about 1. circular incentive effects (log-rolling), and 2. productivity efficiency (only investment spending delivers that; but consumption spending is what causes most investment spending!). There’s almost certainly a tradeoff there between the ultimate GDP-size effects of consumption and investment spending, short- vs long-term.

@vimothy “Now you want me to believe that wealth is a function of… demand? How, if aggregate nominal expenditure increases, does the economy become more productive?”

Yeah: because the increased demand/spending/expenditure incentivizes investment. Which increases productivity. Which lowers prices (relative to less investment). So people can consume more goods and services, be more prosperous.

So you could say that redistribution creates more inflation (relative to not redistributing). Which is exactly Nick’s point, actually… But he’s assuming the overall prosperity effect is the same, whether you change M or V in MV. (He also ignores declining marginal utility of consumption and aggregate utility there, the “doesn’t even touch on” paragraph in my post.)

It’s a behavioral question, not an accounting question: in a monetary economy, what incentivizes producers to increase their productive capacity — to create real capital?

Spending. If there’s nobody ready to pay you for your computer skills, or your cool newly redesigned bicycles, you have no reason to develop them.

Higher investment spending is the proximate cause of higher productivity. Higher consumption spending is the ultimate cause.

@Asymptosis

Steve,

I think my basic objection to the model is that it seems to formalize some not-too-good economics common to the PKE blogosphere–in particular the idea that saving is impossible or bad, that production is unimportant or a given and that there is some mechanism that ties real values to nominal values.

I don’t object to the notion that redistribution is good for welfare or that it could lead to a more productive economy in some or even many cases. As general propositions, I find them to be quite sensible. It’s the way that you’re attempting to model this that bothers me.

(Although I do like the fact that you’re trying to model this formally, which is the only way to go about such things, to my mind, and I agree with a lot of what you’ve said about human capital and wealth).

In the most simple case (like the Ramsey-Cass-Koopmans model), the economy has to allocate resources between consumption and investment, i.e., between consumption and saving. The fact that future income is a function of current investment (or saving, if you prefer) is what creates the dynamic link between today’s saving problem and the state of the economy tomorrow.

In your model, from what I can gather, if I spend $X today, then my income today will be (1.05) * $X. If spend $2X tomorrow, then my income tomorrow will be (1.05) * $2X. Logically, the agents in your model should try to spend their income as fast as possible, since that will make their income grow infinitely fast. If we want future income to be high, we want current income to be high, and that means that spending as much and as quickly as possible.

Aggregate demand is aggregate nominal expenditure. It’s nominal, so it’s just an arbitrary value. If aggregate demand at some future date is 100 currency units, the economy is no more productive than if aggregate demand were 50 currency units.

If that were not the case, we would be able to do all sorts of weird things like add zeroes to the currency and enjoy massive increases in wealth–meaning that the economy has somehow become more productive by virtue of us re-denominating our currency. Or just printing huge amounts of money and giving it away. When everyone receives a free trillion dollars in the post, I expect that aggregate demand will go up quite a bit. And why stop at a trillion? Let’s all have infinite wealth, if that’s available.

Higher investment spending is the proximate cause of higher productivity. Higher consumption spending is the ultimate cause.

How can real income be a function of nominal expenditure?

If you only hang a round with MMTers, you’ll pick up their bad habits. Nominalism is a *very* bad habit.

You want to say that if nominal expenditure is high, then businesses will invest because demand for their products is high.

That’s only relevant at the business cycle level.

Imagine that I can guarantee an increasing nominal revenue. Let’s say that in ten years time, my *nominal* revenue is going to be 1 million currency units. Let’s also say that if I invest today, I can double that. And let’s say that the value of this investment is equal to my current profits *in real terms*.

Is this good? Should I invest?

According to your logic, I want to make my nominal revenue as high as possible.

But if that nominal revenue corresponded to zero real revenue, for example, I would be crazy to waste all of my current profits on it. It’s impossible to say whether it’s a good idea for me to invest on the basis of the information I supplied.

@vimothy “I think my basic objection to the model is that it seems to formalize some not-too-good economics common to the PKE blogosphere–in particular the idea that saving is impossible or bad, that production is unimportant or a given”

Wow I don’t think these are really true at all. The model’s all about producing accumulation from surplus from production. Yes, this mix of investment and consumption is black-boxed (as is the presumed aggregate result of different mixes), but that could be bolted on to the model fairly easily. Just need to decide on the behavioral/incentive assumptions to be coded.

“the idea that saving is impossible or bad”

The problem here is the word “saving(s).” I’d like to challenge you to try something. Have these discussions with me without ever using the word “saving.” It’s not necessary, just gums up our thinking and discussion. Nick’s right that the term should be abolished. I think you use it in different and contradictory ways, with multiple and ambiguous meanings. As JKH has pointed out, in the S=I identity it’s nothing but an accounting construct, a temporary holding place in the accounting structure. I should be called schmegma (avoiding much confusion relating to multiple meanings), or just “gross investment,” which is what it is by definition. (*Net* investment [gross minus CFC] is a actually far better term to describe additions to “national savings.”)

Possibly important typo:

“And let’s say that the value of this investment”

By “value” I really mean “cost”.

@Asymptosis

I don’t agree with Nick or with JKH. With respect to them both, I think that they are wrong.

The concept of saving is very important to economics. They say that Eskimos have hundreds of words for snow (not true according to Stephen Fry). All those different words refer to different aspects of the same phenomenon. Why not just have one word? It would be so much simpler. It’s an argument, but it’s a bit dreary and functionalist, isn’t it?

I’m of the opinion that the word “saving” is meaningful and that it’s meaning is not captured by “investment” or even by something ugly and legalistic like “gross investment minus consumption of fixed capital”.

There’s a I quote that I like in the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics:

Saving means different things to different people. To some, it means putting money in the bank. To others, it means buying stocks or contributing to a pension plan. But to economists, saving means only one thing–consuming less out of a given amount of resources in the present in order to consume more in the future.

It’s this idea of *saving* current resources to increase future resources that “saving” highlights but “investment” does not.

And of course, if you get rid of it, then you can still use investment or some variant of investment to refer to aggregate saving, but you have no word for micro saving.

S = I is not simply an accounting construct. That’s another aspect of the nominalistic approach. There so much focus on accounting among PKE-ers that it causes them to miss the wood for the trees. Saving is equal to investment because for the macroeconomy investment *is* saving and capital *is* savings. Without capital, there can be no saving.

Actually, I think that it would probably only be possible to replace “saving” with “investment” in these highly theoretical, highly aggregated discussions. If we want to talk about anything other than the highest possible level of aggregation, then we lose the identical equality of S = I and we’d need to refer to the investment and net flows to other sectors or aggregates. Much easier to have some variable that we can refer to equal to the sum of fixed investment plus net assets acquired from other sector.

@vimothy “to economists, saving means only one thing–consuming less out of a given amount of resources in the present in order to consume more in the future.”

Fine. By that definition, “saving money” is an incoherent concept.

Because you can’t consume money. (Well I suppose you could chew up dollar bills, but you certainly can’t consume the credit balance in your bank.)

You can only exchange money for other things. (Some of which are consumable.) Spend it. Spending is not consuming.

This is not a quibble. Saving (not consuming) your corn makes sense. Saving (not consuming) your money makes no sense. At all.

By that definition.

An accurate definition of “monetary saving” for an individual would be: spending less than your income within a period. (That says nothing about your consumption-spending/investment-spending mix.)

You’re confusing “spending” with consumption. Or you’re confusing “consumption spending” with consumption. Either way.

In aggregate, “monetary saving” makes even less sense.

We agree that true “national savings” consists of adding to the stock of real productive assets. How do add to that stock? By spending on such productive assets. Hiring carpenters to build a new house. Or engineers to build computers.

If we spend less of our annual income on those things, we “save” money, right?

@vimothy “In your model, from what I can gather, if I spend $X today, then my income today will be (1.05) * $X. If spend $2X tomorrow, then my income tomorrow will be (1.05) * $2X. Logically, the agents in your model should try to spend their income as fast as possible, since that will make their income grow infinitely fast.”

You already said this, and I already replied.

They don’t because of uncertainty. Individuals don’t *know* that they’ll receive that income next year. The model just allocates it to them this way. It doesn’t tell them that it will do so.

You’re confusing accounting certainties with behavioral certainties.

@Asymptosis

Haha–you’ve got me all confused now, I’m not sure! 😉

Steve, you may be right, but I don’t think so. I think you’re probably over-thinking it. If we spend less money on investment, then we don’t save money *overall*. The amount of the money income that we save must be equal to the amount that we spend on investment. If nothing is spent on investment, then there can be no saving.

I don’t agree that saving money is an incoherent concept. Perhaps it’s not as precise as it could be, I don’t know. But If I save some of my monetary income in the present I can consume more than my monetary income in the future. Money is a resource. When I save money, I’m increasing my resources for future use.

That’s why it makes sense to use “saving” in different contexts, because it references the same thing or phenomenon in some essential way–even though the context is different.

So, it’s true that you don’t literally “consume” your income in the sense of eat it. But you do literally “consume” it in the sense of spending it on consumption goods. And you do literally consume it in the sense of using it up. It’s a resource that you use and then it’s gone.

Even if we were to say consumption is the actual act of “consuming” some good or service that we derive utility from, and that you cannot “consume” money, for whatever reason (we derive no utility from, perhaps), so that we can only spend our income on consumption, I don’t see that much is gained by saying “income spent on consumption goods” instead of just “consumption”. It seems like a distinction that is unlikely to matter in most contexts.

I wrote above, “If I save some of my monetary income in the present I can consume more than my monetary income in the future.†I can rewrite this so that it reads, “If I save more than my monetary income in the present, my spending on consumption goods can be greater than my money income in the future.â€

Is there really something important that is concealed in the first construction that’s revealed in the second? Why does it matter?

@Asymptosis

They don’t because of uncertainty. Individuals don’t *know* that they’ll receive that income next year. The model just allocates it to them this way. It doesn’t tell them that it will do so.

If they don’t know, that would still be the best outcome though, wouldn’t it?

What if demand was as high as it could be, so that by definition there was no lack of aggregate demand. Some of that demand would be consumption and some investment. What determines how the two are split? Because that is what is determining the rate of saving.

More accurately, there’s something determining investment, and there’s something determining the “something else”, the human capital residual.

Is that something spending, in whatever form? The only way I can think of is if spending consistently exceeded expectations and the economy was always below a potential level.

Steve, I realize that I’ve gone on at you at some length and it might is probably annoying. Thanks for chatting to me about your model. I do appreciate it and I do like reading your blog. I worry sometimes, because it’s easy on the internet to come across like some anonymous asshole and it’s not intended that way. It’s also a lot easier to be some anonymous asshole than it is to put your thoughts up on a blog to be criticized.

@vimothy

It’s really about careful definition and use of terms. I don’t think that happens in most economic discussions. Again, I think you’re prey to this widespread problem. You’re not alone.

I’m coming to the notion that “saving” and “investment” should only be used in their vernacular senses: individuals saving money (spending less than their income in a period), and buying financial assets with those savings. Since depositing a check in the bank is buying a financial asset (credits in your bank account at that bank), in these usages saving quite obviously equals, even is investment. Duh.

But real national saving is the net creation of enduring real assets. Instead of calling it “saving,” we should call it…creation of enduring real assets. Or something.

Using the same word for two different things is really confusing.

Yes on the mix of consumption spending vs. investment spending. I’d like to bolt that on to my model, but need a formula where the mix is a function of individuals’ wealth.

Would also need a formula that specifies the effect on total production/surplus resulting from different mixes.

I’m guessing that the latter formula would graph nonlinearly, probably a U shape or reverse U shape? Update: Either too much investment or too much consumption (as a proportion) would result in less production/surplus. Need to hit the goldilocks spot?

[…] a recent post I built a model with one rich person and ten poorer people to ask: does redistribution from rich to poor make us all more wealthy? The conclusion was Yes. Jump back there to see a quick rundown of the model’s […]

“I’ve set it up so that income (including the surplus) is distributed to the population proportionally based on how much they spend. It’s a somewhat arbitrary choice (I had to make some choice), but since people’s incomes and expenditures do tend to correlate fairly closely, it doesn’t seem like a nutty one.”

I don’t understand why we should assume that one’s spending should be at the same proportion to their income at all income levels (in the model it’s at 1:1.05). Earlier in the essay you stipulate to a decreasing marginal utility of consumption, which to me implies that at higher income levels, people will spend a lower proportion of their income.

If you change the model so that the rich person’s Annual Surplus is 125% instead of 105%, then you end up with higher wealth after 20 years in a 0% redistribution scenario (224%) than in a 1% redistribution scenario (209%).

@Marcotte

Since this is basically a divvying of the 5% surplus across the population, if we upped the richer person’s income to 1.25x spending, the poorer people’s income would drop below their level of spending. I suppose we could bolt on a lending mechanism and outside lending source to compensate for that…

Unless you’re saying that rich people’s spending actually *causes* a higher surplus… That’s where I was going with notion of bolting on different investement/consumption mixes for rich and poor people, and some formula for how those different mixes affect surplus levels.

@Asymptosis

You are proving that the concept of money is extremely confusing. Money is not the same as REAL items and thus your model makes no sense at all. You need to step back and understand how a real economy works and think about exchanging and producing real products through the use of labor and other real products (capital). Remember that money itself is just a way to make such exchanges simpler. It is not REAL in its own sense.

How can an economy produce more if it doesn’t have the capacity (capital, labor) to do so? You have to look at both the production side AND the consumption side – you can’t simply ignore one and assume that it just runs alongside the other.

[…] my model here and here looking at how (re)distribution of wealth affects demand, hence production, […]

[…] And since those workers have a high propensity to spend their income, all things being equal that distributional shift should mean there’s a higher average velocity of money, aggregate demand, NGDP, etc., all in a virtuous cycle. (See JW Mason here and me here.) […]

[…] And since those workers have a high propensity to spend their income, all things being equal that distributional shift should mean there’s a higher average velocity of money, aggregate demand, NGDP, etc., all in a virtuous cycle. (See JW Mason here and me here.) […]

[…] can see a simple arithmetic model of this thinking here and here, and download the spreadsheet to play with it […]

[…] can see a simple arithmetic model of this thinking here and here, and download the spreadsheet to play with it […]

[…] a model to look at the long-term economic effects of upward and downward redistribution. Posts here and […]

[…] The use of decision rules based on explicit mathematical calculation, combined with a utility function in which monetary wealth is the only argument. […]