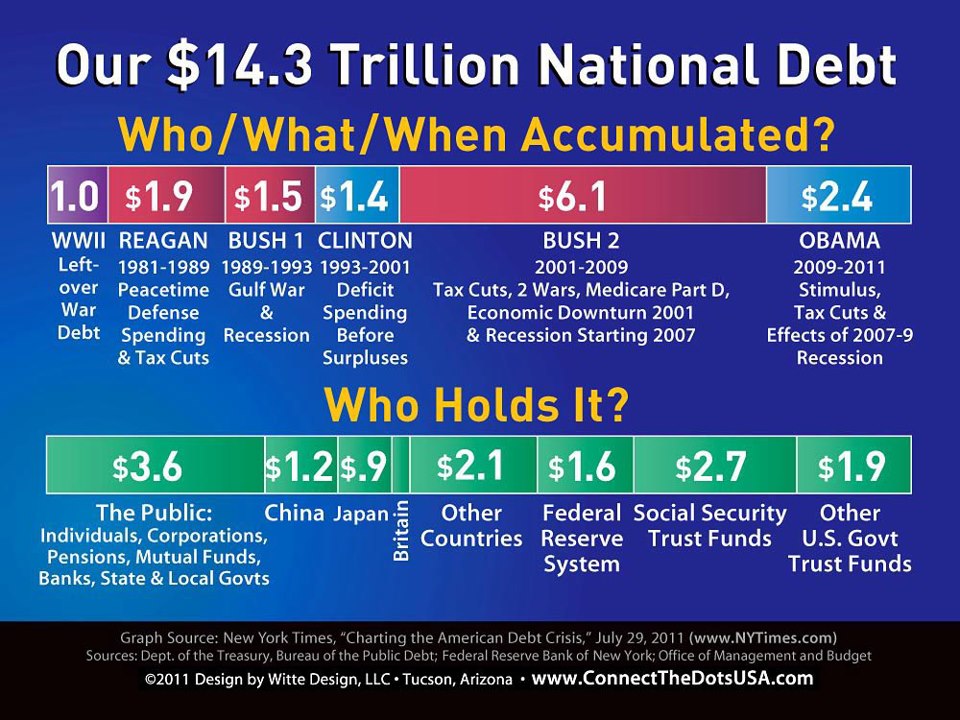

A friend of mine posted this on Facebook:

I started to explain it, but realized that the standard usage is wildly screwy and confusing for any normal human, and decided to explain it here instead.

The problem is that even in standard economists’ usage, “public” is used in two different ways:

1. “Public” debt: debt owed by the government. In this usage, “public” means “government.” It’s sort of metaphorical: the government r us. As in “the public [versus the private] sector.” “Public debt” is often called “gross public debt.” That includes money “owed” to Social Security, etc.

Note that these debts to trust funds don’t in any way represent the liabilities of those programs; they’re pretty much arbitrary numbers, accidents of the moment, bookkeeping artifacts of a political/ideological construct, that are best ignored if true understanding is the goal. “Gross public debt” a.k.a. “public debt” — the $14.3 trillion shown in this graphic — is not an even vaguely useful figure in understanding the fiscal position of the country or the federal government.

2. “Debt held by the public” (not the public as described in this graphic): in this usage, the public is exactly not the government. It refers to debt held by non government — including other governments, and private holders in other countries. This is often called “net public debt.”

Watch: two (contradictory) usages of the same word, in one equation!

Net public [government] debt = debt held by the public [non government]

You can see this if you search for “public debt” on Fred. Or, read this wikipedia graph caption:

Red lines indicate the debt held by the public (net public debt) and black lines indicate the total public debt outstanding (gross public debt), the difference being that the gross debt includes that held by the federal government itself.

It’s no wonder people are confused.

This graphic makes it even more confusing, because “the public” here is the domestic private sector plus state and local governments. And it excludes foreign-held debt, which is included in the normal definition of “debt held by the public.”

This is the fault of the New York Times, which uses the term in the infographic from which this graphic is prepared. Not only do they start with the gross figure rather than the more useful net figure, but they use “the public” in a completely idiosyncratic way.

A further complication: in standard usage, “debt held by the public” includes Fed holdings, even though the Fed is part of the government. The interest it is paid (by the Treasury) on government bonds is paid right back to the Treasury. (The presumption is that those bonds will eventually be sold back to the private sector.) This is not usually such a big deal, but these days the Fed is holding 17% of the Debt Held By The Public.

I suggest the word “public” should be eradicated from all these usages, in favor of more descriptive and precise terms. “Public” does nothing but confuse if you don’t know exactly what it means. Instead, say things like:

Net federal debt.

Net federal debt minus Fed holdings.

Federal debt held by the domestic private sector.

Government debt [including state and local]

And etc. The bookkeeping at this high level is not actually very complicated, so hopefully careful usage will help people better understand and discuss fiscal issues.

Update: JKH in the comments suggests an excellent, immediately understandable and precise term: Treasury debt. Use it!

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

21 responses to “It’s No Wonder People Don’t Understand the “Public” Debt”

On the right track…

Try “Treasury debt”

Held by … etc.

i.e. the institutional approach

describing it the way you’d describe the Fed flow of funds report – sources/uses etc.

The curious part is that money loaned to the govt is called debt and is a bad thing, but money loaned to banks is called deposits and is a good thing. The solution is obvious, rename public debt, “public deposits”.

http://media.liveauctiongroup.net/i/13898/14073391_1.jpg?v=8CF6647D6DABD60

@JKH: “Treasury debt”

I LIKE it! I’m going to start using that. Think we could get FRED to change over? 😉

@beowulf: “public deposits”

Also nice. When you buy a U.S. government bond you’re depositing your money in “The U.S. Treasury Bank.”

I don’t think it would make sense to most people, though, and for good reason, because unlike bank deposits,

1. the money you’ve “deposited” cannot be withdrawn on demand. It’s more like buying a CD from a bank, and when people buy CDs from banks, they don’t refer to it as “making a deposit” because they can’t “make a withdrawal.” Also:

2. You can sell your bonds. You can’t really “sell” your bank deposits, except in the kind of metaphorical language that us dweebs tend to use in these types of money discussions.

“Deposits” generally carries these two meanings for people, so using the word to describe bond holdings would just be confusing, I think.

“When you buy a U.S. government bond you’re depositing your money in “The U.S. Treasury Bank.—

Absolutely not, in case you’re referring to my own concept of a “Central Treasury Bank”.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/97524996/JKH-Treasury-and-the-Central-Bank

But quite likely you’re not and maybe your not familiar with my idea of a CTRB – no matter.

Anyway, the whole idea from my perspective was to reject this sort of ambiguous language.

The CTRB (my concept) has the flexibility to issue either/both deposits (reserves) and debt – at its option.

There is no language ambiguity in that concept – just as there isn’t with “Treasury debt” in the existing institutional arrangement.

But Treasury debt is NOT a deposit with the Fed in today’s institutional arrangement. That’s the whole point.

CD is short for…

The link is to a certificate of deposit issued by the (now-defunct) Postal Savings System. To be clear, JKH is correct that this does not reflect current institutional structure, however so fr as I can tell, Congress can change this structure without violating any laws of physics.

JKH,

Can you elaborate? I was under the impression that the purchase of treasury bonds gives the government deposits that it can then use to credit private accounts with. how is this now a deposit with the Fed?

how is this NOT a deposit? sorry.

Treasury bonds are a liability of the US Treasury – on the books of the Treasury.

They are not a liability of the Fed, and not on the books of the Fed.

Just have a look at the Fed balance sheet if you need to be convinced of that.

And they are no more a deposit with the Fed than your mortgage liability is a deposit with your bank.

Beowulf is correct on the potential for Congress to change the institutional structure. And he’s right on the physics as well.

But you don’t describe actual institutional structure as if its been changed.

And I think that goes to the point of the post – which is appropriate, unambiguous language to describe the debt in question – not to describe a potential transformation of institutional structure and the debt that is part of it.

What is disturbing to some, including me, is the propensity for those with an agenda for change to describe the world as if their agenda has been achieved, rather than in an honest way as the the world that we are currently dealing with, whatever our individual objectives for the future happen to be. There is far too much of this cultish language manipulation around, in my view. Some even build entire schools of economic thinking on that sort of “foundation”.

@JKH: No, I hadn’t read that piece yet even though I’ve been fully aware of its existence. Even I, dweeb that I am, was daunted by the 9,000 words. Halfway through and it’s pretty great. I love functional vs. strategic.

Waiting to respond here till I’m done with that. Hope you’re still watching…

@JKH:

Alright, have now Read The Whole Thing. Excellent. Your CTRB — Fed and Treasury consolidated — is #2 here:

http://www.asymptosis.com/thinking-about-the-fed.html

But as I requested there, more carefully constructed than mine.

As I think you probably remember, I’m also quite (conceptually) interested in #4, which basically turns all the commercial banks into branches of the CTRB. In this full consolidation there is only one bank, all transactions just move money between accounts at that bank — with the exception of unfunded purchases by that bank (fiscal/government spending in excess of taxation), which create new money in deposit accounts.

I was quite interested by this:

“Treasury’s deposit account at the central bank serves the same functional purpose as a commercial bank reserve balance. The fact that it’s not referred to as a reserve account is neither here nor there in terms of understanding the functionality of the system. One may as well think of the Treasury account as just one more reserve account.”

That leads me to wonder (my usual semantic fixation…): Maybe we should stop using the word “reserves” (which very few people understand) and just call them central bank deposits.

And, how does this work for you?:

“When you buy a *newly issued* U.S. government bond you’re a *strategic though not operational* depositor in “The U.S. Treasury Bank.â€â€

From my strategic perspective I’m moving money from my bank account into a treasury account, creating a (non-demand) “deposit” there that I can withdraw when the bond matures.

I actually don’t think this is very important, except as a mental exercise in thinking about accounting structures at various levels and combinations of accounting consolidation. Still doing my pushups…

Steve:

“Here are four ways to look at the Fedâ€

There’s only one way to look at the Fed as an institution, IMO, and that’s your # 1.

(There also tends to be counterproductive debate about “independenceâ€. There is some confusion that mistakes operational co-ordination with Treasury for lack of independence. Independence pertains to policy – mostly interest rate policy. And the fact is that the Fed is independent in that relevant dimension – until it isn’t – which is also subject to Orwellian spin that it’s not. It IS independent – today – now)

The other three ways look at the consolidated balance sheet effect of institutions interacting with each other, without changing those institutions – unless specific institutional changes are proposed. I don’t see that in your earlier piece.

Here’s the important point of truth, IMO:

There’s a difference between the view of a joint institutional effect on consolidation, and an institution that is a specific construct of consolidation in itself.

The “CTRB†I constructed is of the latter type.

It is NOT your # 2. MMT is your # 2. I avoided direct reference to the latter where possible, but in fact there is enormous ambiguity of descriptive language in that approach.

The whole point of the CTRB construct is that it’s unambiguous. It’s an explicitly constructed institution, with a different set of accounts than what exists in the current institutional arrangement. This difference may seem to be a nuance, but it’s not, IMO.

“Maybe we should stop using the word “reserves†(which very few people understand) and just call them central bank deposits.â€

I hear you, and have considered that, but have no firm opinion at this point – unlike “Treasury debtâ€, which is an obvious slam dunk (in my mind – looks like you agree). “Reserves†(which include but are not limited to “reserve balances†has the advantage of being factually correct, but may be functionally sub-optimal as descriptive language.

I’m not clear on tearing down that fence until I’m convinced how best to improve on it.

But there should be a way. “Central bank deposits†– maybe; not sure.

“When you buy a *newly issued* U.S. government bond you’re a *strategic though not operational* depositor in “The U.S. Treasury Bank.â€

Sorry. Doesn’t work for a consolidated view (IMO), and doesn’t work for a consolidated institution (e.g. CTRB). In the former, I don’t think it is meaningful. In the latter, you hold a bond issued by CTRB. It’s explicitly not a deposit. And “strategy†is the purview of the issuer in that construct.

I actually think this stuff is important, possibly more than you do.

Language is important – as in Orwell.

And cults flourish in conditions of language ambiguity.

Sorry, in a bit of a rush – don’t mean to come across as curt.

(BTW, I’m planning a post at MR on the “Chicago Plan†which has a lengthy discussion that is strongly tangent to your point on reserves.) Hope it will be up there in about a week.

@JKH “Language is important”

You sure won’t find me arguing with that. I’ve just been realizing how many of my recent posts are responses to sloppy and even unconsidered language use in economics discussions.

Lemme say what I think you’re saying in my own words, see if I’ve got it right:

Telescoping, or consolidating, the financial statements of existing institutions (Fed plus Treasury, for instance) does not properly represent — actually distorts — the picture of those institutions’ financial positions and practices. The only way to present that type of consolidation accurately is to imagine an already-consolidated institution, then depict that consolidated institution’s financial position and practices using a different accounting structure.

Here’s what I’d like, in as few words as possible: what is the negative effect of doing the former? Where’s the hurt? I’m not at all challenging with this question. Just want to hear what you think.

Oh to add: when I buy a treasury bond, it’s not useful in economics discussion to call it “making a deposit” because it’s certainly not a demand deposit as the term is commonly (and clearly) used. But I still find it useful for my own conceptual work to think of it as a deposit.

Think about a dollar bill. I think of it as a physical token of a credit tally entry. A credit with whom? Well it’s a “credit” with anyone who will take it in exchange. But the where’s the credit tally entry? Let’s try this:

For institutional reasons, I can’t take that dollar bill to the Fed and get anything else in return for it (like reserves, for instance — I don’t have an account there and they won’t set one up for me).

But I can take it to their “agent,” my corner bank, and deposit it. They get another dollar of reserves, I get a different asset — $1 on deposit that they owe me, an addition to my credit balance — and they get a liability entry.

Now suppose they don’t need that dollar, so the next time they get dollars from the fed they ask for one less than they would have otherwise. That effectively adds a dollar to the Fed’s vault, increases the banks reserve balance (their Central Bank Deposits balance) by a dollar.

Now the next time the Fed needs dollars, it orders one less from the Treasury. So the Fed owes Treasury one less dollar.

And if I wanted to, I could walk into the Treasury (at least virtually) and give them that one dollar along with my 1040 showing one dollar taxes owed, to expunge that liability.

In this sense, telescoping everything, that dollar bill in my pocket is equivalent to a dollar in the Treasury Bank.

I know this is all pretty silly (and I’m in a hurry and think I got at least one of the signs reversed in the above), but it helps my think about the accounting. It just probably wouldn’t help to use that thinking in discussions with others.

@JKH: I see this language in a paper on the chicago plan:

“only demand deposits subject to a 100% reserve requirement in lawful money and/or deposits with the Reserve Banks”

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp/76.pdf

That language is making even more sense to me, cause otherwise a bank’s vault cash (for instance) is part of reserves but it’s not reserves. Think that’ll confuse anyone?

@Asymptosis

No hurt in that at all – provided you distinguish between the two.

If you don’t, then you risk seeing such nonsense as “the government neither has nor doesn’t have money”, which is absurd as a description of how our monetary system actually works. It very much obscures the fact that the fiscal entity (Treasury) very much does or doesn’t have money. And that’s an interesting thing to know if you’re actually interested in the facts – rather than absorbing like a zombie what is an ideological driven spin that is driven by an implicit rejection of the wisdom of the actual operational arrangement that is in place. If you’re going to question it, question it directly and describe an alternative in an intellectually honest way. Don’t muddle the distinction between fact and non-fact.

On the other hand, it does makes sense if you construct a hypothetical institution whose design conforms to that particular description. And if you do that, and distinguish between the actual and the counterfactual – then you’ll be clear on the operational difference between the two – which is a real difference, and its an interesting difference, and it may lead to a better, clearing understanding of what the advantages and disadvantages are of setting it up either way.

@Asymptosis

I have no problem with the consolidated view. I promoted it strongly years ago in discussions with Steve Waldman, when the MMT blogs were just getting going. And I still promote it, although most wouldn’t see that or would choose not to see that because I’m also promoting the distinction between the two. Being interested in the consolidated view shouldn’t mean becoming disinterested the unconsolidated view.

I know at the end of the day that the consolidated Treasury/Fed has three main types of liabilities – reserves, currency, and bonds. I can look through it all and see that I or my bank has a choice of what mix of those three to hold. That’s interesting, but it can’t be the only thing that’s interesting.

As far as generalizing everything to the level of a bank demand deposit, that’s inappropriate IMO for two reasons:

a) it makes no sense unless you generalize the treasury/fed consolidation to be a bank – and that’s a specific assumption about institutional design, which is the very idea of the CTRB as a specific institution. So there’s a contradiction there between goals of generalization and specificity.

b) I don’t think of my banking opportunities on the liability side to generalize to deposits at all. I hold demand deposits, fixed deposits, bonds, preferred shares, and common shares. Why on earth would I generalize all that to a demand deposit? And so why would I do it in the case of the government. The reason that certain groups do it is because of ideological bias – they want to squeeze interest margins out of the banking system, so they reduce everything to the lowest common denominator in terms of yield – which is the demand deposit. Well, sorry, but that doesn’t work for me. I like my bank stock and my fixed deposits, thanks.

@Asymptosis

The language I tend to use for reserves is banknotes and reserve balances.

Reserve balances is probably short for reserve deposit balances. But I tend to avoid putting ‘deposit’ in there because I like to save that for commercial bank deposit liabilities. I.e. I try to avoid using deposit in a potentially ambiguous way for both reserves as an asset and deposits as a liability.

Also, there are interbank deposits (usually Eurodollar deposits) as assets or liabilities, so the deposit distinction is more reserve versus everything else.

That’s my approach – not sure anybody notices or cares but that’s how I try to distinguish between what is a component of “high powered money” (reserve balances) and endogenous money (bank deposit liabilities or (Eurodollar interbank) assets).

To make things more complicated, Fed funds as assets are usually called Fed funds sold – which again avoids deposit language on the “high powered money” (HPM) side.

Conversely, Eurodollar deposits, asset or liability, are not HPM.

I imagine all that is useless to you, but it helps me sort it out.

@JKH: “they want to squeeze interest margins out of the banking system, so they reduce everything to the lowest common denominator in terms of yield – which is the demand deposit. Well, sorry, but that doesn’t work for me. I like my bank stock and my fixed deposits, thanks.”

I’ve often said: just because people want or think they deserve to earn interest on perfectly safe assets (I’m just talking about treasuries here) doesn’t mean the government is in any way obligated to provide that. They could just issue issue dollar bills instead of treasury bills. I really like SRW’s proposal a while back for interest-protected government deposit accounts, with a holdings limit of circa $200K. This would serve a socially useful purpose. I’m not at all convinced that government bonds serve such a purpose. Perhaps seriously the contrary.

I know that’s somewhat different from your wanting bank deposits vs bank shares, but maybe not all that different given implicit and explicit government guarantees.

“reserves as an asset and deposits as a liability”

I think of both as both assets and liabilities. In that sentence you’re being a bank, right? Signs reverse if you’re the Fed in the first instance or a bank depositor in the second. You know that of course but it sort of shoots a hole in the reasoning for your semantic choice, no?

I think “Fed deposits” is nicely parallel to “bank deposits” — people/companies deposit in banks, banks deposit at the Fed. I think the modifiers — Fed deposit — make the distinction quite clear.

That reserves the word “reserves” for a very particular usage — assets held by banks (currency, [Fed deposits], bonds [, other stuff?]) against demand-deposit liabilities.

Again the alternative is that the bank has reserves that aren’t reserves. I get it, you get it, but…

I’m kind of lost on the interbank and Euro stuff, maybe if I understood I’d change my mind on the language.

You and I aren’t going to solve the sloppy language problem out there, but I do appreciate talking it through and getting clearer, so at least we can be precise in all our superior virtue. 😉 As I think W.H. Auden said, “How do I know what I think till I see what I say?”

@Asymptosis

“I’ve often said: just because people want or think they deserve to earn interest on perfectly safe assets (I’m just talking about treasuries here) doesn’t mean the government is in any way obligated to provide that. They could just issue issue dollar bills instead of treasury bills.”

Only if the government abandons active interest rate management as part of monetary policy.

I.e. that choice equate to a permanently zero policy rate.

So you have to argue why that’s superior to the existing system.

Otherwise, there’s active interest rate management.

Which means interest rate risk – for the issuer and the buyer.

Which gets priced by the market in government bonds.

Government bonds aren’t “perfectly safe” because of this interest rate risk.

@Asymptosis

“I think “Fed deposits†is nicely parallel to “bank deposits†— people/companies deposit in banks, banks deposit at the Fed. I think the modifiers — Fed deposit — make the distinction quite clear.”

sounds OK that way

@JKH “Only if the government abandons active interest rate management as part of monetary policy.”

Right. Though the rate paid on Fed deposits could still control the bottom, no? My flippant suggestion begs for a rigorous conceptualization of how the institutions would operate under such a regime.

I’m looking forward to reading your conceptualization of the institutions and practices that would/might exist under a Chicago Plan.