James Livingston once again sheds serious light on our current situation, as illuminated by the Great Depression.

Condensed:

- Economic recovery was actually going gangbusters ’33-’37.

- It wasn’t because banks started lending; they didn’t.

- The government (Reconstruction Finance Corporation) was doing the lending.

- We should try doing the same thing now.

More detail on those four statements below. Here’s the heart of his argument:

…reports of the Comptroller of the Currency tells us that the banks sat out the recovery. The summary Table 47, “Total Assets and Liabilities of National Banks, June 1933-June 1937,” Report of the Comptroller of the Currency 1937 (Washington: GPO, 1938), pp. 488-94, shows that during the recovery, [banks’] total deposits increased 52 percent, holdings of government securities increased 57 percent, and (idle) reserves held with Federal Reserve banks increased 140 percent. Meanwhile loans and discounts–that is, the extension of credit to businesses and/or consumers–increased only 8 percent.

So there was an economic recovery from the depths of the Great Depression with no financial fix, or rather with almost no participation by the banks, except of course that.they bought the government securities that financed net contributions to consumer expenditures out of federal deficits. And no nationalization, either. How is that possible?

In short: the Reconstruction Finance Corporation replaced the banking system as the lender of first resort to businesses large (the railroads) and small (most of its loans were under $100,000). The volume of its loans and discounts during the four years of recovery was roughly five times that of the national banks.

The way to deal with the current crisis short of nationalization may, then, be to bypass the moribund banking system with a new RFC capitalized with the remainder of the TARP and other funds authorized by Congress.

Back to those four statements:

Economic recovery was actually going gangbusters ’33-’37.

The reversal and repudiation of Hooverite creative-destructionism under Roosevelt really, really worked, as evidenced by many economic indicators. The big impact was from monetary loosening after three years of churlish stupidity at the Fed and Treasury ’29-’32. But the fiscal stimulus policies (though actually rather tepid in those years) also contributed, at least by making the monetary moves more effective.

Tyler Cowen has been making this argument with some cogency for some time (with some serious pushback from moi in email back-and-forths, which he has been kind enough to engage in). I’m somewhat grudgingly coming around to his view, especially since Christina Romer made the same point very strongly just the other day at Brookings (PDF), concluding:

Had the U.S. not had the terrible policy-induced setback in 1937 [both monetary and fiscal], we, like most other countries in the world, would probably have been fully recovered before the outbreak of World War II.

She’s referring to both fiscal and monetary tightening in 1937–fiscal tightening (cutting spending and increasing taxes) driven by deficit fears, and monetary tightening driven by misplaced technical anxieties at the treasury and the fed.

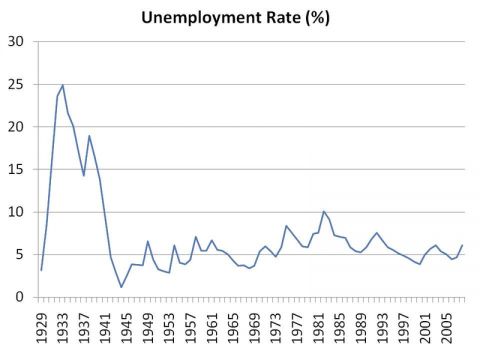

Even the weakest indicator in this period–unemployment–had plummeted from 25% to 15% ’33-’37. It surged back in ’38, but then continued its downward trend into the war years.

Another crucial issue which has not been widely discussed: Alexander Field demonstrated in his 2003 paper, “The Most Technologically Progressive Decade of the Century” (PDF), that the 1930s saw growth in “multifactor productivity” (largely technology-driven) surpassing anything before or since. This goes a long way to explaining why employment and employees were slow to feel the benefits of the recovery. Productivity was skyrocketing, so less workers were needed for each unit of output.

It wasn’t because banks started lending; they didn’t.

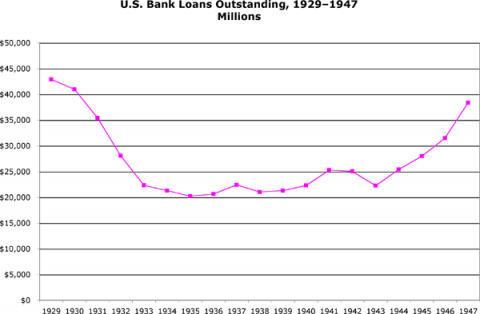

Livingston lays out the numbers in the passage above, but even his numbers give the banks more credit than they deserve. Here are the numbers from All-Bank Statistics: United States 1896-1955, available as honking-huge scanned PDFs from the St. Louis Fed.

After diving off a cliff between ’29 and ’33, the size of banks’ loan books basically didn’t change at all in the years 1933-1940. (Thanks for the help, guys!)

The government (Reconstruction Finance Corporation) was doing the lending.

Compared to the banks’ failure to lend (despite massive government prop-ups), RFC lent approximately $5.8 billion in the years 1932-1937. This makes it look like the government accounted for all the new net lending over those years.

We should try doing the same thing now.

I don’t know enough to say whether direct government lending would offset the counterparty disasters that would result from letting the banks fail. But from a moral (and moral hazard) perspective, it sure is tempting to throw all those government dollars at direct loans–and let the banks go hang.

Comments

2 responses to “Banks? Who Needs ‘Em?”

[…] April 18, 2009 · No Comments Banks? Who Needs ‘Em? […]

[…] of posts in the right sidebar that will give you the “facts on the ground.” Start with Banks: Who Needs ‘Em. It gives the numbers and graphs, and you’ll probably actually like what I have to say […]