Update: You can find a followup post including some brief answers from Robin Hanson (and my commentary on same) here.

My gentle readers will undoubtedly remember a question I’ve asked repeatedly: as technology steadily increases productivity, will we (have we) come to a point where a large portion of workers can’t do “valuable” enough work to earn a decent living? Where only the technologically adept, and owners of technology, “merit” liveable earnings?

My thinking is not particularly original. As Robin Hanson points out in the presentation I’m about to discuss, it goes back at least to David Ricardo. who went after this subject quite rigorously in 1821 (The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, 3rd Edition).

Many will say (not without grounds) that my thinking is simplistic, amateurish, and silly. The most powerful argument that my concerns are groundless or stupid: invoking history in the form of The Luddite Fallacy:

If the Luddite fallacy were true we would all be out of work because productivity has been increasing for two centuries.*

If technology is making human labor less valuable, how do you explain the steady, seemingly inexorable rise in wages/earnings/GDP per capita (choose your measure) over the last century or two? (Yes–if you look globally–even over the last few decades.)

That, by my lights, is a bloody strong argument. How does one respond to it?

It’s a question I’ve struggled with mightily, not only to protect my pet theories but because of a feeling that something was missing. And I think I’ve found an answer in Robin Hanson‘s “Economics of Nanotech and AI” presentation at the Foresight 2010 conference. (Liberal-bashers take note: Robin is a quite devoted if decidedly idiosyncratic libertarian.) If you’re a reader like me you’ll find much of the matter, more quickly, in Robin’s IEEE Spectrum article, “Economics Of The Singularity“–though if you’re feeble-minded like me you’ll also need to view the presentation and the slides (PowerPoint) to understand his insights.

This is probably old-hat to many who are better-versed than I. But it’s something of an aha! for me, and may be likewise for some of my readers.

Here’s the heart of his matter, a debate economists have been having for centuries: do machines, does technology, complement (I would prefer “augment”) or substitute for (I would prefer “replace”) human labor? If all technology does is augment human labor–making each person more productive–that increased productivity is purely good and all boats rise (at least over the long term, though obviously with local disruptions, both temporal and geographic, that societies might want to address and ameliorate.) If technology replaces human labor, then some portion of the population, over time, will get squeezed out, with no opportunity to “earn” a share of the increased production. (And/or, wages for labor will decline.)

So which is it–does technology complement or substitute for human labor? Augment or replace? My immediate, uninformed answer is “Yes. Both.” But I’ve had no idea how to quantify those effects, or characterize their interactions.

The economic consensus (as I’ve discerned it and as Robin reports it) is that it’s all complement/augment–substitution is only local and temporary. And two centuries of rising wages certainly give a great deal of weight to that position. But it still seems more likely to me, even obvious, that both occur.

Which leads me to wonder: How do the two effects interact? What’s the ratio of the two? Does that ratio change? Most interestingly to me, has that ratio changed in any steady way over the decades and centuries?

Happily, it turns out that Robin is a Yes man like me:

I want to help you understand how they can both be right. (22:32)

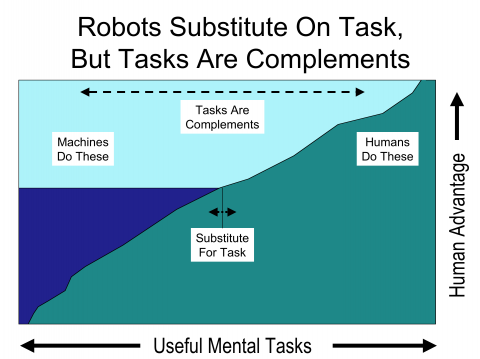

He explains it with the following waterline model.

Machines do (obviously) take over human tasks, replacing human labor in those tasks, as machines gain a “better relative ability” to do those tasks than humans. No doubt about it. That’s the point where the waterline meets the shore, where a task can be equally well/efficiently done by a machine or a human. And the waterline is obviously rising.

But (not shown) those machine tasks complement the (more cognitive/creative) tasks that humans still do–and give humans time to do those tasks–increasing the humans’ productivity. (Robin explains: “The tasks themselves are all complements–and this is a very robust, standard thing [in economics]–the better the world economy does any one thing, the more valuable doing all the other things becomes.”) This makes the human effort steadily more “valuable,” so the humans can produce more with machines’ help, and because the humans’ work is valuable, those humans can claim their share of the increased production. Sounds great.

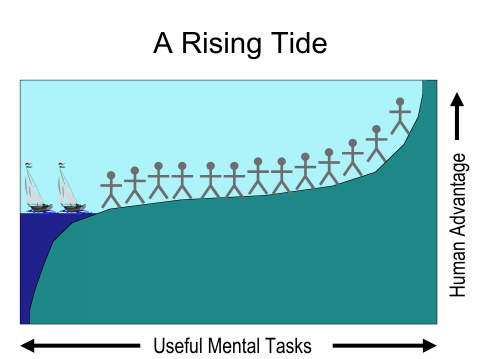

Another way to think about it: humans can only migrate so far above the waterline. They need that vast body of technology–that body of water at their back–to expand into new territories.

It’s worth pointing out that there’s an unstated presumption here: that the graph continues up and to the right, that humans can climb to ever-higher levels–leaving lesser tasks to machines while we tackle tasks that deliver ever-greater value per hour–ever-greater productivity. (Designing more efficient cars instead of building cars.) Assuming that everyone shares in that greater prosperity (as everyone has, in the long historical picture though certainly not in detail), this truly is an all-boats-rise scenario.

But here’s where things get interesting–when Robin changes the shape of the shoreline:

The land contour is actually a graph of the change in the complement/substitute ratio. Sometimes one effect dominates, sometimes the other. On the left, machines’ takeover of human tasks does more to complement human effort than it does to substitute for that effort–resulting in economic growth and human prosperity. (To repeat: this rosy view reflects a big-picture, long-term orientation. Some individuals can’t make the steep climb, and they drown. But humanity moves ever higher.)

But then that ratio changes–the shoreline flattens out, and the scenario shifts radically. For every increase in machine abilities, there’s more substitute, and less complement. But the water keeps rising.

It looks to me like a lot of people just drowned, while a lucky few remain perched on the precipice.

Here’s Robin’s explanation:

There’s both a substitution and a complementary effect. And which dominates depends on the shape of this curve. Down here where it’s very steep you have very little substitution and a lot of growth. The machines getting better basically means people get richer, wages rise. But we could also reach a point [slide change] where there’s a large flat region in principle, and we could have the wave of water coming in, to a point where most income in the world is going to the machines, and a relatively small fraction is going to the people, and depending on the shape of this shoreline it might simply flood the entire region.

Unlike the future that Robin’s envisioning, though, in our world machines have no claims on earnings–they aren’t “people,” so they don’t get income. Their owners do. So he’s describing a situation “where most income in the world is going to the [owners], and a relatively small fraction is going to the [workers].”

Robin says this quite explicitly in his Spectrum article:

Wages could fall so far that most humans could not live on them.

This is, to my understanding, exactly the situation that the Luddites (and many others since) were so concerned about.

Robin is rather blithe in his statement that “in principle” there could be a large flat region. His talk has heretofore argued that periods of rapid growth (the steep parts of the curve) occur, highlighting the agricultural and industrial revolutions. And he asserts that those periods are getting closer together. He also asserts that another one is imminent–he thinks in the next hundred years.

Which would suggest that we are currently in one of those flat periods, where you see a lot more substitution relative to complementing–where a lot of people are being squeezed out of the economic system (drowned), without commensurate gains via complementarity (machines’ increased ability to produce things–and help humans produce things–that humans value).

Let’s hope the hill keeps going up to the right, and that humans have the capacity to keep climbing.

But here, perhaps, is the issue: many don’t. While measured IQ has been increasing over the decades since it was first measured (they keep having to recalibrate the test to achieve the 100 median), it’s not increasing anywhere near as fast as machines’ abilities. It’s possible that a large group of humans–at least in advanced, knowledge-driven societies like the U.S.–are being left below the waterline.

There’s much more I’d like to say on this topic, but I find myself out of time. (And I’m thinking you might be as well.) So I’ll just leave you with the questions I posed for Robin on his blog (slightly modified and expanded here).

Robin:

Your augment/replace waterline model is, IMHO, profound. To bring it down to our current situation:

Have we reached that plateau? Perhaps sometime in the 70s, give or take?

Is it related to the limits of (aggregate) human cognitive capacity? IOW, since 50% of people have an IQ below 100, and “valuable†knowledge-worker tasks are requiring ever-greater cognitive skills, can the ameliorating effects of education continue to maintain the augment/replace ratio, as they did for much of the twentieth century?

Since machines currently are not people, but are owned by people (so the machines’ earnings go to the owners), could this explain the increasing wealth and income disparities (labor vs. capital, wages versus rents) in recent decades?

Re: your much-less-than-satisfying answer to the question about Germany’s success (highly industrialized, but with major social programs): is it possible that in order to maintain demand for ever-more-efficient productive capacity, government redistribution is a necessity? No–not at 1,000 times some imagined level, but somehow relative to per-capita shares of production?

Given that individual utility functions (as measured by “happinessâ€) seem to flat-line at about $15K in annual income in developing countries, about $60K in the U.S. (yes, iffy stuff, but the threshold/flat-line seems likely at some level), can the demand from a small cadre of owners–who don’t “value†most goods very highly–provide the demand necessary to keep the economic log rolling?

Could the absence of this widespread demand–making it difficult for capital to find productive investments that pay a good return–explain the massive increase in “casino investing†over recent decades? A desperate search for returns in a world where demand does not reward valuable production?

Could this situation also explain the downward pressure on secondary-education budgets? A vague sense of (impending) declining returns to education?

Could it also explain the rapidly increasing lengths of “jobless recoveries” since the 70s?

Is it possible that the current…difficulties are like a wave crashing on that plateau?

IOW, because of the limits of human capability, could the Luddites (finally) be right? Even a stopped clock…

Comments

22 responses to “Are Machines Replacing Humans? Or: Am I a Luddite?”

No we haven’t reached a flat plateau yet. Only a small fraction of world income now goes to machines, and a flat part could easily trigger a faster growth mode. No, redistribution is not required to maintain demand, and utility functions do not “flat-line.”

@Robin Hanson

Thanks for answering, Robin.

>Only a small fraction of world income now goes to machines

What about to owners of machines? I assume that’s what you mean? Source?

>a flat part could easily trigger a faster growth mode

Well obviously, one always precedes the other. Triggers…how quickly? (In the long run we’re all dead and all that…)

>No, redistribution is not required to maintain demand, and utility functions do not “flat-line.â€

I’ll just take those as facts then, and ignore everything else. Thanks. (Though it seems contrary to your beliefs, and certainly mine…)

Yes a small fraction to owners. Less than 10%. The transition would take less than ten years.

Ten years seems a bit fast, how exactly would the economy be changed that quickly? Simply physically deploying the necessary technology takes time (not to mention integrating them into the wider system) and even then you have to deal with the inevitable growing social resistance to it as it displaces more people (which I think we’re in the early stages of, just mis-aimed at off-shoring). What would you say are the lower bounds for the amount of time the economy can double?

I personally think we’re undergoing two simultaneous technological revolutions. The first is that machines are increasingly able to challenge people in the one major remaining role they have in production – computation (which is also critical in other areas). Thereby humans are no longer necessary for supply (I would date this to the late 70’s early 80’s, the peak of American manufacturing employment). The second is that information has essentially become free (Generating novel information still has a price).

I would suggest that both of these are a major cause of the series of bubbles we’re undergoing. Since people are no longer necessary for supply, the number of people employed can no longer serve as a check on the economic growth (in the industrial era, supply was bounded by how many people you could find to fulfill the requisite computational rolls). It can grow regardless, therefore a valuable signal to investors and ‘creators’ has been lost. Combined to that, novel ideas (‘memes’) can be spread and implemented quickly, but we have yet to develop ways to properly evaluate them (kept in check in the past by the cost of preserving and distributing distributing it). One idea can cause growth, people know about it and before long everyone is adopting it before all of its implications are understood. Therefore, it is used in excess without any of the traditional brakes until the flaws in the idea(s) aggregate and the system becomes too unstable.

Chris, good insights, it seems to me.

This is all feeding the feeling that many seem to have: that some fundamental aspect(s) of the economic dynamic have changed since the 70s, at least in the U.S. (And that it’s not all due to the 30-year hegemony of Reaganomics–though I believe that has exacerbated the effects.)

It strikes me that the increase in technology (capacity and distribution) vis-a-vis human cognitive capacities may be a key aspect. Because human cog caps don’t change much, and tech obviously does.

Improved education maintained the ratio for most of the twentieth century. Can it continue to do so? Has it, since the 70s? The numbers suggest “maybe not.” If not, will increasing numbers of people fall below the waterline?

If as a society we’re hitting this cognitive limit (which was not true when the Luddites held sway, or for the past 200 years), that fact may answer the challenge of The Luddite Fallacy.

Which I guess would make it the Luddite Fallacy Fallacy…

@Asymptosis

At the beginning of the 20th century, cognitive capability was heavily distributed throughout all economic strata and substantial arbitrary and economic barriers kept it there. The industrial era made these arbitrary barriers untenable (as doing so was highly inefficient) and society was forced to remove them. This resulted in the mass sorting of society by cognitive ability, those at lower strata that had high ability were able to climb up and put their abilities to better use. This is the main social legacy of the industrial revolution, the elevation of intelligence as the primary determinant of social value (and why people are so resistant to the idea of intelligence).

At this time, in the United States, this sorting is mostly finished (although it is by no means perfect) as judged by decreasing social mobility. Most of those that could benefit from much greater access to education (it wasn’t really ‘improved’) have benefited. Now we’re going to see an increasingly widening gap between ‘haves’ (creative elite) and ‘have nots’ (people who would have traditionally filled computational roles) and accelerating social problems associated with it.

@Chris

*Very* good point, which I had not brought up. Spectacularly efficient cognitive sorting since 1900, and especially post-war, while the waterline rises.

I’ve actually done a fair amount of thinking on this recently actually. Here is some of what I’ve come up with:

Human economic activity can be broken down into three primary areas:

A. Production – the acquisition and fashioning of resources to create items of value as well as distributing them

B. Creative/Problem Solving – the creation of novel ideas and tools as well as fixing problems in both tools and society as well as directing the distribution of resources

C. Human services – dealing with, helping, controlling, and administering people

For almost all of human history, people were primarily focused on A. The acquisition and creation of the means of survival, namely food, was their highest priority.

The three economic activities can be further broken down in to their primary inputs:

Production: Energy, labor (the work necessary to produce something of value), and computation (the execution of a series of logical steps for a desired result)

Creativity/Problem Solving: Information (the gathering and communication of novel data and ideas), computation (the aggregation and transformation of data into a usable form), and creativity (the generation of new, useful ideas)… See More

Human Services – Information (data on human desires and states), human interaction

Again, most human economic activity was focused on production (primarily energy in the form of food), although people did stray into the other two from time to time.

Up until the industrial revolution people were primarily limited to producing food. The industrial revolution made people unnecessary for the energy and labor parts of production, but they were still critical for computation. Since society’s food needs are finite the massive boost in farm production made having large numbers of people unnecessary. This freed them up for industry (and other activities such as creativity and human services) where machines were able to provide energy and labor, but computation was still critical. Demand is also far less finite and the new machines and energy sources opened up entire new areas of demand. Therefore, society was able to redeploy the population into a computational role in a vastly expanded economy (not over night mind you, it took the better part of two centuries and some would say longer). This defined the social/economic order up until the late 1970’s/early 1980’s (the industrial order).

The invention of the transistor is, along with realizing seeds can be grown into plants, the single most important invention in human history. Scientific and technological advancement was requiring more and more computation, something humans tend to be inefficient at. The first artificial computers were huge, slow, and limited. This kept them constrained to a few niche applications. The transistor was initially like this, too limited due to its size, but it could be made smaller, much, much smaller. For a time, shrinking it simply broadened the number of niche applications it could be used for. In the late 1970’s it became small enough (and thereby powerful enough) to begin filling computational roles held by humans. The computational limit had been lifted and this marked the end of the industrial era.

@Chris

Continued from above:

The lifting of the computational limit meant that humans were increasingly unnecessary in production (‘supply’). The effects were small at first, and the concurrent elimination of the costs of information (also enabled by the transistor and increase in computational power) masked it, but improving computational power and better algorithms have resulted in it being able to take on an increasing number of roles in production and in the computational side of creativity. Hence, due to what I have already laid out in another post, there are no longer any limits to supply or controls on creative pursuits. We now have the problem that we have far too much information and have not developed the tools to evaluate or sort it. Therefore, investors and creators have no negative signal and can continue pursuing activities and novel ideas way beyond what is prudent. Until those mechanisms are developed (and they will be), we are likely to see a continuing series of bubbles driven in large part by the unconstrained application of innovation (innovation itself will be hindered by information overload).

In the mean time, people who normally filled computational roles are increasingly displaced (United States manufacturing share is about equivalent to its share in 1980 even while its work force has dropped significantly). Those who are able to fill more creative or highly skilled human service rolls will (we’ll likely see an increasing amount of innovation in all sectors of the economy due to this, but also more competition at the top). Whereas those who are incapable of providing either of these roles will increasingly compete for the dwindling number of production computational roles that are not readily automated and low skilled human services positions (which society doesn’t require enough of to take in all of those displaced in production), hence the massive rise in the services sector in the last couple decades.

As a side note, fiscal and monetary policy will likely become increasingly ineffective as a means to create jobs due to supply’s increasing independence from the human population.

Apologies for virtually take over your comments section.

@Robin Hanson

http://www.asymptosis.com/robin-hansons-reply-to-the-luddites.html

The problem with the argument is that it assumes that the shape of the land contour isn’t determined by what decisions humans make in the first place. The Luddite argument assumes that machines replace human labor because what humans do is essentially fixed.

This is not the case. Machines do not replace human labor but change how work is done and thus changing the working area of human labor. Capital transforms what can be done with labor and this argument doesn’t consider that factor.

Robin’s argument could be updated to say that rate of the capital substitution in the production process compared to the rate of labor transformation is uneven thus creating the “drowning tide” i.e. creative destruction.

But what is really happening? I suggest that when we see that rate of capital substitution it not because economy is becoming more efficient but rather the rate of labor transformation is declining or what Galbraith calls economic diversity (in productive sectors) is actually in decline.

The decline creates the illusion that productivity is increasing when in reality it is decreasing because the standard metric of units per worker per time unit doesn’t in fact measure other factor in productivity e.g. number of changes per unit, per worker per time unit e.g. the rate of tool/product design.

The flaw in standard economics is that it assumes that value of productivity is measured purely in terms of the price of the unit being produced relative to its cost over time but this is not the value. The value is the transformation of the work relative to cost over time.

The question of how to avoid Robin’s drowning tide is simple a question of rational economic organization and not market forces versus Keynesian redistribution. The question is how do we produce enough creativity and new fundamental discoveries where the objectives of work can transformed into the new modes of labor?

In short it’s about producing more people that can essentially design and invent more modes of work that they produce machines to do that work.

Therefore what we need is not so much a welfare state but rather a super CCC job programs building state of the art infrastructure.

People need productive work not “make work†jobs or simple welfare. Let’s say that we produce a super machine that lets one worker produce 1000 cars per hour. Rather than firing all the others workers we simple have then build maglev trains instead of cars.

It doesn’t matter how good the machines get at copying human labor if we are constantly changing what we do with human labor thus technology can never replace human labor because no digital system or mechanical system can be creative in terms of non-linear dynamics because they are linear and binary.

If you want the science behind the non digital human creative cognition I will be more than happy to discuss why all the talk about general AI, Mind-uploading, and future sex with androids is nonsense and anti-science.

@Septeus7

“Therefore what we need is not so much a welfare state but rather a super CCC job programs building state of the art infrastructure.”

I agree with you 1000%. I include infrastucture and public works projects in my rather broad and loose characterization of “redistribution.”

IOW it’s not just taking money from the rich and giving money to the poor (though that’s both economically and morally necessary, to some extent, IMO); it’s taking money from the rich and investing it in common public goods.

For whatever reasons, excessively “free” markets don’t do this very well. They inevitably concentrate wealth and beggar the commons, with manifold negative consequences for all. Government “redistribution” is the only solution we know of.

@Septeus7

“It doesn’t matter how good the machines get at copying human labor if we are constantly changing what we do with human labor thus technology can never replace human labor because no digital system or mechanical system can be creative in terms of non-linear dynamics because they are linear and binary.”

What people are missing, is that most people are this way too. They [i]cannot[/i] handle the complexity and non-linearity necessary for economically useful creativity.

Broadly speaking, the roles people perform in the economy [i]are[/i] limited.

Construction is limited by some non-linearities (particularly navigation) at this time. However, a number of these can be ‘faked’ by a sophisticated enough binary system.

Quote from Asymptosis: “IOW it’s not just taking money from the rich and giving money to the poor (though that’s both economically and morally necessary, to some extent, IMO); it’s taking money from the rich and investing it in common public goods.”

My problem is that you still putting things into monetarist terms i.e. take the rich people’s money and then use that for public benefit.

But you’ve already lost the battle when you concede the idea that the propertied classes have anything that society at large needs or wants.

Money derives its value from national productivity and it is the rich who have created a redistributionist system for wealth via contracts and business law.

The question is how one creates a system where a “harmony of interest” is realized in the widest possible distribution of capital ownership which would thus tend to equalize all men. Now this not Utopian because it understood as a process of forever becoming but I mention the idea of “harmony” as direction rather than a state which we to achieve.

In short, we face a cultural challenge where the social classes are constantly pitied against each other in social Darwinian warfare but act according to the Westphalian principle of each acting toward the benefit of the other because it is in your benefit to do so. In short, the ruling (bullying) class needs to learn that fairness and sharing makes everyone happier and better off.

P.S. Asymptosis I consider myself a Conservative and I’m quite socially conservative but I’ve turned against what today’s reactionary right calls “Conservative” because 19th century liberal economic radicalism isn’t “Conservative” and in today’s context it’s destructive so it’s better to keep the New Deal than become neo-fascists or neo-feudalist.

Call me a Prog-Con.

Quote from Chris: “What people are missing, is that most people are this way too. They [i]cannot[/i] handle the complexity and non-linearity necessary for economically useful creativity.

Broadly speaking, the roles people perform in the economy [i]are[/i] limited.â€

Economic history teaches us people when nations are in cultural decline people start believing that surf-like mentality that there’s nothing else I can do but be a hunter like my father. Economic growth by definition involves the development of increasing kinds of occupation.

In the beginning, people thought the only roles was a hunter or gatherer then somebody thought it would be a good idea to poke a stick into the ground and drop a seed into the hole and thus civilization was born and then later folks decided that piling rocks on each other protect gain stores was a good idea and then the economy had a mason industry.

But the only way any economy has ever grown is because folks started using their imagination because they believed that they had one and that roles aren’t predetermined by a feudal caste system.

Quote from Chris: “Construction is limited by some non-linearities (particularly navigation) at this time. However, a number of these can be ‘faked’ by a sophisticated enough binary system.â€

I’m sorry but I’m talking about process of creating non-linear dynamics itself. No machine can invent new applications of non-binary non linear dynamics any more that it can invent a new human language or classical ironic poetry or predict the stock market perfectly using statistics.

Only after a human has discovered that kind of dynamics can it be formalized and taught to a machine.

You are making the same error that Archimedes who thought derivation of the circle was a reduction of quadrature but when monks in Florence proved that notion to be wrong they created a revolution in human culture and economy.

Physical science is based on the dynamics of physical geometry which are higher order of dynamics than a binary process and binary processes can never generate creative scientific discovery for the same reason no amount of quadrature can generate a circle.

That’s my basic of the argument against strong AI and Strong Singularity but a more formal argument could be made using various physical dynamic systems (the physical catenary curve is a good example) and simply showing that they are not modeled correctly by a binary system and are operating on a higher function thus no digital system could generate any useful model.

Now if you created digital-analogue hybrids your might be able to get very close what humans can do but no one is developing technology along those lines.

So we have just created another “job en potentia†for humans to solve just by discussing the nature of human technology. The very conversation proves that we have a lot of work to do and for now most of it will be done by humans if we ever get our act together and change our economy including our education so that we can clearly work on these problem without people getting confused on basic issues such what classes of functions or relations can generate what and what they cannot generate.

Perhaps a Strong Singularity is possible but it is not close and we are barking up the wrong tree as far as I am concerned.

@Septeus7

Thanks for the comment, Septeus. My main point–I don’t know if it’s the same as Chris’s–is that more and more of those “jobs en potentia” are beyond the wherewithal of an increasingly large proportion of the population–that we may be reaching a point at which past history is no longer predictive.

Machine abilities are increasing ever more quickly, while human cognitive skills are not. Don’t we eventually–well short of any AI-based “singularity”–have to reach a point where many humans are simply incapable of competing?

“each acting toward the benefit of the other because it is in your benefit to do so”

My thinking *exactly.* I call it mercenary morality. And I think progressive economic policies (redistribution via infrastructure, health care, education, and wage support [i.e. EITC]) enact exactly what you’re talking about.

The empirical evidence suggests that this is true:

http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/clip_image00221_thumb.gif

Even the rich get richer under Democrats.

There are fifty more graphics out there to support that one.

@Septeus7

“People need productive work not “make work†jobs or simple welfare. Let’s say that we produce a super machine that lets one worker produce 1000 cars per hour. Rather than firing all the others workers we simple have then build maglev trains instead of cars.”

You have no idea how automatization works. Change type of work is one of the biggest advantages of automation. Imagine 1 million workers need reskilling. You must retrain each one worker. With machine, you must retrain 1 machine and make 1 million copies. What sounds simpler to you?

And don’t make yourself vain hopes. There is not one human job which cannot be eventually done by machine more efficient. Even compose music or writing stories. People are, in proportion against machine, unreliable, with very short focus on work, must often take breaks, sleep, ilness, holidays, family affairs, attention variability.

@Septeus7

So your argument is simply: Because AI is digital, it cannot make useful models of analogue world. In fact, sound is analogue, but its model on CD is digital, and is accurate enough for us as would be for AI. In fact, even now we use AI for solving real world problems because it is better than any human in it, especially in logistics and manufacture planning.

“AI Planning methods were used to automatically plan the deployment of US forces during Gulf War I. This task would have cost months of time and millions of dollars to perform manually, and DARPA stated that the money saved on this single application was more than their total expenditure on AI research over the last 30 years.”

[…] Hanson was nice enough to drop off a drive-by comment in response to a recent post of mine (responding to a presentation of his), a post that espoused my Luddite Fantasy. His […]

[…] looked at this in some depth — with much thinking help from Robin Hanson — here, here and […]

[…] post is in reference to the following articles: http://www.asymptosis.com/are-machines-replacing-humans-or-am-i-a-luddite.html and http://www.overcomingbias.com/2010/03/econ-of-nano-ai.html Professor Hanson gave a fascinating […]

@Chris

Well, you did, but it was very worthwhile. You’ve gathered together in one picture several thoughts that were floating inchoately in my mind for years. Much to think about, thanks.